The Sunday Signal: K.I.T.T. Would Have Had Wi-Fi

When the future arrives in your driveway but not on your train.

Essential Insights on Tech’s Impact, Leadership Lessons, and Navigating Human Potential Issue #21 – Sunday 7 September 2025

⏱️ 10 min read

The Bottom Line Up Front

Last week, we explored Red Bull, reality, and the limits of AI. This week, we turn to the border between fiction and fact. From Knight Rider’s talking car to today’s autonomous vehicles, science fiction has an uncanny habit of predicting the future. In my Yorkshire Post column, I reflect on the fragility of GPS and why quantum clocks will define the next era of security. And finally, I take aim at Britain’s railways, where the absence of reliable internet says everything about how the North is left behind.

When Fiction Becomes Fact

On Saturday evenings in the 1980s, I would sit down in front of the television for a double bill: first Knight Rider, then Minder if I was allowed to stay up. The highlight was K.I.T.T., a car with flashing lights and a voice that could argue, reason, and joke with its driver. It could scan fingerprints, analyse chemicals, drive itself in “Auto Cruise” mode and even race in “Super Pursuit” mode. At the time, it was thrilling precisely because it was impossible.

Michael Knight, played by David Hasselhoff, even had a futuristic LCD radio watch branded for the show. He used it as a Commlink to call K.I.T.T., summoning his car with a flick of the wrist. Who knew we would have this technology for real forty years later? The Apple Watch makes Knight’s gadget look quaint. Today we can not only talk into our watches but pay for groceries, send health data to our doctor, and stream music while we jog.

Four decades on, much of that fantasy is now standard equipment. Conversational AI is everywhere, from Siri to Alexa. Cars routinely respond to voice commands. Biometric scanning is how millions of us unlock our phones. Collision avoidance, adaptive cruise control and self-parking are no longer science fiction but options on a family saloon. Even night vision and advanced sensors are becoming normal on high-end models.

The red scanner bar that once symbolised K.I.T.T.’s supernatural awareness has modern equivalents in lidar and radar, guiding prototypes of fully autonomous cars through real streets.

Science fiction has a habit of predicting the future. Star Trek’s communicators prefigured mobile phones. Dick Tracy’s two-way wristwatch became reality. HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey looks eerily like today’s AI systems, always listening and sometimes unsettling. Even the Starfleet “tricorder” has echoes in portable biosensors and handheld medical scanners.

Not every leap has been made. K.I.T.T.’s indestructible molecular shell and shapeshifting nanotech skin remain beyond our grasp. Amphibious sports cars are still a novelty. But nanomaterials are reshaping armour, and amphibious vehicles do exist in military and specialist markets.

The lesson is clear. What seemed impossible on a Saturday night in the 1980s is often the stuff of reality by the 2020s. Science fiction does more than entertain. It primes our imagination, pointing to the inventions that will eventually sit in our pockets, on our wrists, and in our driveways.

GPS is Fallible, We Must Trust Quantum Clocks

My weekly column in the Yorkshire Post

In the summer of 2013, pilots lining up passenger jets for landing at Newark Liberty Airport suddenly lost their GPS signals mid-approach. The satellite-guided system faltered, forcing aborted landings and panic among engineers.

The culprit was not a foreign agent but a £20 GPS jammer plugged into the cigarette lighter of a van. A truck driver had bought it to stop his employer tracking his movements while he slipped away for clandestine trysts.

Federal agents traced the signal, fined him $32,000, and he lost his job. What seemed comic exposed a serious weakness in the technology on which modern life depends.

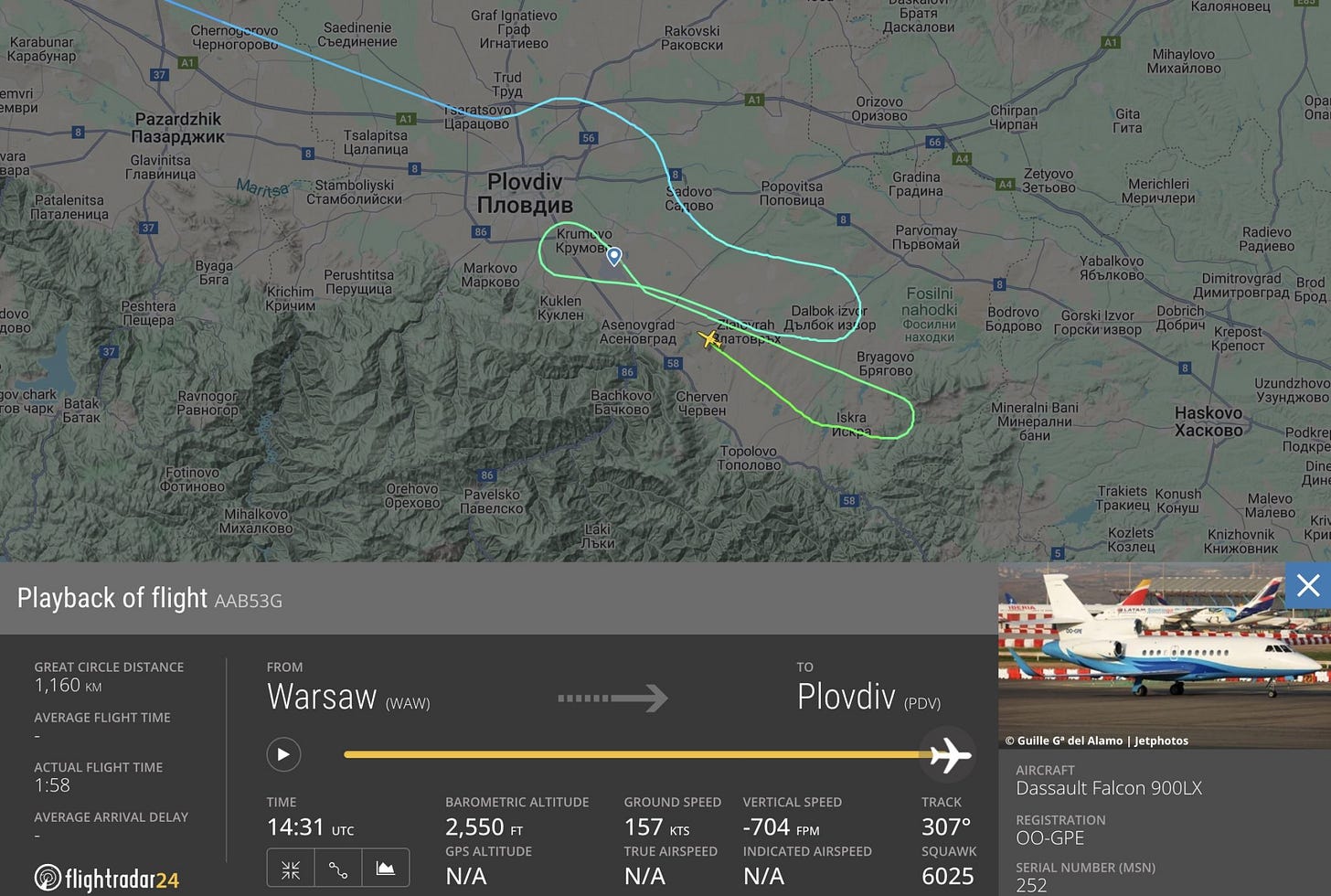

Fast forward to this week, and the plane carrying Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, was forced to divert and land using paper maps after its GPS navigation failed over Bulgaria. Officials suspect the culprit was Russian jamming. The symbolism could not be clearer.

The leader of Europe, flying into a region on Nato’s flank, was reduced to the tools of the 1940s because the digital compass of the modern world had been switched off.

Russia’s campaign of interference has turned GPS disruption from a curiosity into a constant menace. Since the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, tens of thousands of incidents have been logged by airlines flying over the Baltic states. Pilots report spoofing, where fake signals replace the real ones, sending aircraft astray. Military flights have also been targeted. Last year, an RAF plane carrying Britain’s Defence Secretary experienced spoofing near Kaliningrad.

Some regulators downplay the risk, pointing out that aircraft use multiple systems, not just GPS. But this level of interference is a cause for concern.

GPS has become the bloodstream of the digital age. Beyond aircraft, it guides ships, synchronises stock exchanges, keeps mobile phone networks ticking, underpins precision agriculture and most worryingly, precision-guided missiles and defence systems. A tool designed by the US military to give soldiers a battlefield advantage has become a universal utility, yet relies on ultra-weak signals beamed from satellites some 20,000km above Earth. A pocket-sized jammer can drown them out.

That fragility is no longer acceptable. If GPS can be spoofed or jammed, then it cannot be the backbone of critical systems such as missile defence. The West needs something more resilient. Enter the quantum clock.

Put simply, GPS works because satellites carry highly accurate atomic clocks. Each one broadcasts a timestamp. Receivers on the ground compare signals from multiple satellites, calculating their location from the differences in arrival time. Jam the signals, and calculation collapses.

The quantum solution is to build clocks so accurate that each aircraft, ship, or missile effectively carries its own internal GPS. Britain is already a leader in this field. Birmingham, Glasgow, and Oxford laboratories are working on portable atom clocks that may one day be housed in a cockpit or warship bridge. Making them small and affordable enough to be employed on a mass basis is another thing. But the principle has been proved: if you cannot trust the sky, trust the atom.

We must invest now in quantum-equipped resilience and break free from a satellite chain that can be severed at will.

Read My Column In The Yorkshire Post

No Signal on the Midland Main Line

There are few things more frustrating than trying to work on the train from Sheffield to London. Laptops open, deadlines looming, and the internet drops out before you even reach Chesterfield.

George Gibson’s recent analysis of mobile coverage on the Midland Main Line lays bare the scale of the problem. Vodafone customers spend an average of 1 hour 42 minutes without dependable service. For EE it is 1 hour 46. Three and O2 are even worse. On a two-hour twenty-three-minute journey, passengers are offline for most of it. Median download speeds on some networks sink to below 4 Mbps. That is worse than dial-up in the 1990s.

This is not a minor inconvenience. Modern work depends on constant connectivity. Most business is conducted in real time, through cloud services, live documents, and video calls. If I can stream Netflix on a transatlantic flight and access 5G on parts of the London Underground, why is Britain’s main artery to the North still a dead zone?

The government has trumpeted Project Reach, a partnership to lay 1,000 kilometres of fibre optic cable and eliminate mobile blackspots across key routes. It is a fine announcement, but the rollout will not begin until 2026 and may not be complete until 2028. By then, we will have lost a decade of productivity to frozen screens and failed connections.

Once again, the North is told to wait. Once again, the promise of modern infrastructure arrives late, if at all. Faster trains are irrelevant if the time on board is wasted. Twenty minutes saved on the track is meaningless compared to two lost hours without internet.

Connectivity is no longer a luxury. It is a foundation of economic life. The South should not get seamless broadband while the North gets buffering wheels. If Britain is serious about levelling up, it must start by connecting its own people.

📖 Data credit: George Gibson

🚀 Final Thought

Fiction, Fragility, and Frustration

Knight Rider’s car reminds us that ideas once laughed at can become daily reality. The communicator watch, the self-driving car, the talking assistant that never sleeps. All of it seemed absurd until it became ordinary. Fiction is often the first draft of the future.

But while the future arrives quickly in some areas, it exposes fragility in others. GPS, the invisible bloodstream of the modern world, can be crippled by a £20 gadget. Ursula von der Leyen forced to navigate on paper maps is not just a story about aviation. It is a metaphor for how easily the scaffolding of modern life can be pulled away.

And then there is the frustration. On Britain’s Midland Main Line, passengers sit in silence, staring at buffering wheels, disconnected from the digital economy. This is not just an inconvenience for commuters. It is an act of self-sabotage for the nation. Productivity, opportunity and trust leak away when basic infrastructure fails. The South gets seamless broadband, the North gets empty promises and another lost decade.

The thread running through all three stories is simple. Technology does not arrive evenly. It dazzles in some places, collapses in others, and leaves too many people behind. The challenge is not inventing the future. We are good at that. The challenge is building it wisely, securing it against disruption, and sharing it fairly.

Science fiction shows us what is possible. Quantum clocks show us what is necessary. The Midland Main Line shows us what happens when excuses win out over ambition. If Britain is serious about leading in technology, it must prove it not with speeches but with action that reaches every carriage, every region, and every citizen.

The future is already here. The question is whether we will rise to meet it, or allow it to pass us by on a train with no signal.

Until next Sunday,

David

David Richards MBE is a technology entrepreneur, educator, and commentator. The Sunday Signal offers weekly insights at the intersection of technology, society, and human potential.

© 2025 David Richards. All rights reserved.

CONNECT WITH ME: LinkedIn | Twitter | Website