The Sunday Signal: The Power of Illusion

On bans that create empires and theories that question reality

Essential Insights on Tech’s Impact, Leadership Lessons, and Navigating Human Potential Issue #20 – Sunday 31 August 2025

⏱️ 10 min read

The Bottom Line Up Front

Last week, we explored how bans and prohibitions can ignite curiosity and drive success. This week, we look at three very different lessons. My Yorkshire Post column traces how Red Bull turned regulatory panic into one of the sharpest marketing campaigns in history. We then turn to the mind-bending question of whether our universe is a simulation, a hypothesis that physicists are now daring to test. And finally, we end on a lighter note with Taco Bell’s drive-through AI being bested by a single mischievous customer and 18,000 water cups.

The Allure of the Ban

My Weekly Column For The Yorkshire Post

I have a confession to make. As a naive twelve-year-old, I bought a copy of Relax by Frankie Goes to Hollywood. I had no idea what the lyrics really meant. I bought it because it was banned. Mike Read banned it on Radio 1. Days later, I sat glued to the Top 40 countdown, as Tommy Vance reached number one but still could not play the record. The next morning, I walked down Fargate in Sheffield and handed over my pocket money at WH Smith. The ban gave it power. It gave it mystery. Most of all, it gave it sales.

People want what they are told they cannot have. Prohibition created the bootlegging fortunes of America’s roaring twenties. Schoolyard bans fuelled the appeal of cigarettes. And in more recent times, restrictions turned a little-known Austrian energy drink into a global empire.

Red Bull began life in Thailand in the 1970s, where a businessman, Chaleo Yoovidhya, sold a syrupy tonic called Krating Daeng to lorry drivers and labourers. It kept them awake through punishing shifts. It would have almost certainly stayed local had Dietrich Mateschitz, an Austrian toothpaste salesman, not discovered that it eased his jet lag. In 1984, he struck a deal with Chaleo. They formed Red Bull GmbH, reformulated the drink, added fizz, and launched it in a slim silver can aimed at students and nightclubs rather than truck stops.

Regulators reacted with panic. France, Denmark and Norway banned its sale. German officials warned of heart risks. Instead of killing the brand, the bans made it irresistible. Students smuggled it across borders. Clubbers bragged about finding it. Newspapers fanned the flames. Red Bull became contraband in a can.

From there came lift-off. Today Red Bull sells over 12 billion cans a year in 170 countries, pulling in more than €10 billion in revenue. Forbes values it at over €20 billion. But Red Bull is more than a drink. It owns two Formula 1 teams, football clubs in four countries, a record label, television channels and one of the sharpest content machines on earth. When Felix Baumgartner leapt from the edge of space in 2012, he was not just skydiving. He was proving that Red Bull had become a cultural phenomenon.

The co-founders became fabulously wealthy. Chaleo Yoovidhya, once a poor farm boy, rose to be Thailand’s third-richest man. When he died in 2012, his family inherited a majority stake in Red Bull and remains in control today. Dietrich Mateschitz became Austria’s richest man and built an empire spanning sport, media and culture. A drink once banned in Europe now sits at the heart of two dynasties.

What it shows is simple. Scarcity and controversy can light the fuse, but only strategy and relentless execution keep the rocket in the air. Frankie Goes to Hollywood soared to number one on scandal, but their career faded when the shock wore off. Red Bull turned prohibition into the best marketing campaign money could never buy, then used it to build a global empire.

Business leaders should take note. Scarcity sells. Exclusivity excites. People crave what they are told they cannot have. But when the mystery fades, the real work begins. Entrepreneurs who succeed are those who turn curiosity into loyalty and hype into scale.

As for me, that twelve-year-old in Sheffield clutching a copy of Relax learnt an early lesson in the psychology of desire. Bans can ignite the fire, but only great businesses keep it burning. Frankie fizzled. Red Bull soared. The question for today’s entrepreneurs is simple: when the ban is lifted, will your business still have wings?

Read My Weekly Column in the Yorkshire Post

Are We Living in a Simulation?

Elon Musk has said many times that the odds we are living in base reality — the true, physical universe — are “one in billions.” His reasoning is rooted in the trajectory of technology.

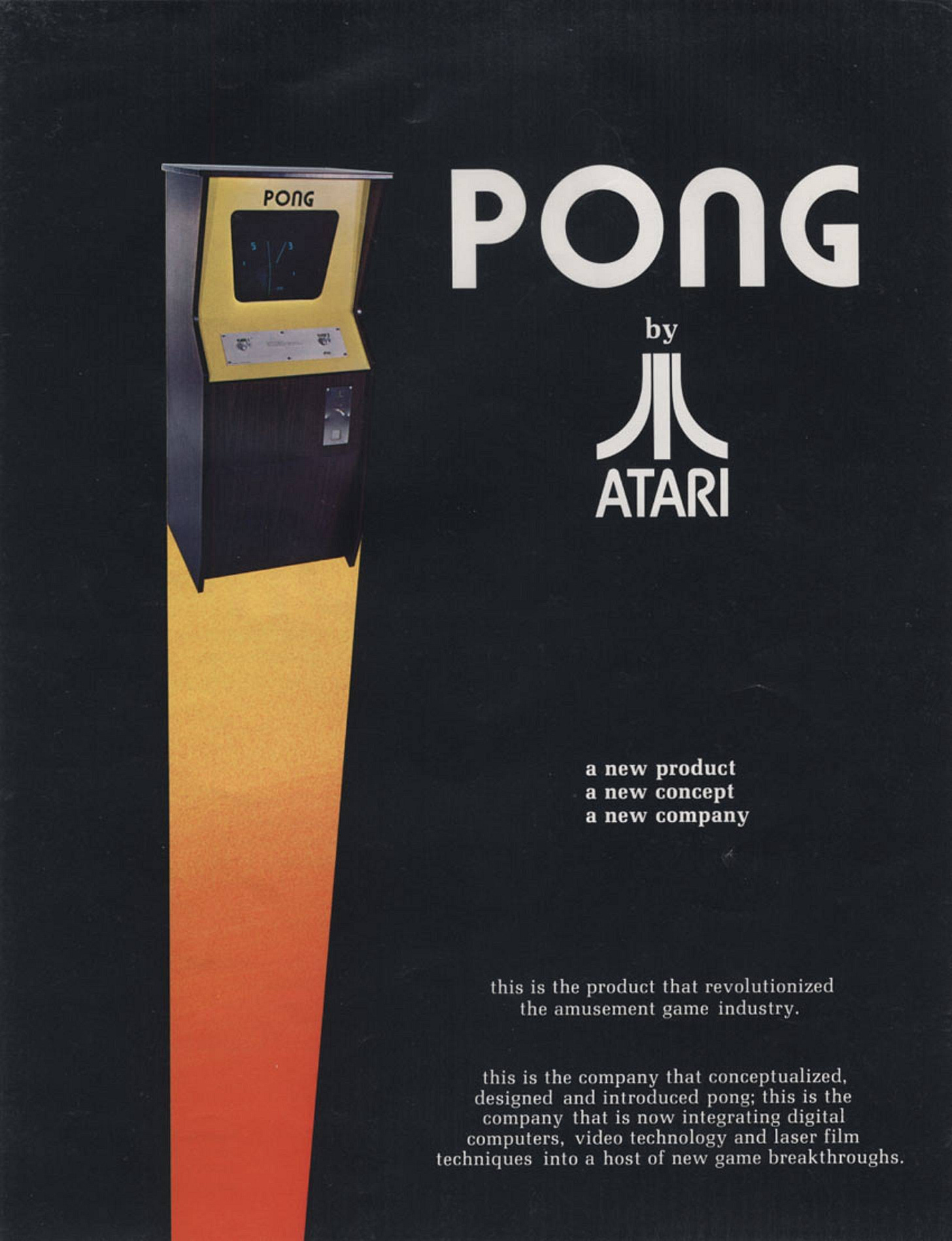

He points to Pong, the 1972 video game consisting of two rectangles and a dot. In half a century, those primitive graphics have given way to photorealistic, high-resolution 3D worlds played by millions simultaneously. If computing power continues to advance, Musk argues, the games of the future will be indistinguishable from reality itself.

Now imagine billions of such simulations running across countless advanced civilisations. Statistically, the odds are overwhelming: we are far more likely to be inside a simulation than in the single, original universe. Musk goes further. If we are in base reality, the only explanation may be that no civilisation has survived long enough to reach the point of building simulations — a conclusion he finds profoundly worrying, since it implies advanced societies tend to self-destruct.

The framework comes from philosopher Nick Bostrom, who formalised the “simulation hypothesis” in 2003. His trilemma is stark. Either civilisations like ours destroy themselves before developing the technology. Or they survive but show no interest in creating “ancestor simulations.” Or — if they do build them — then simulated beings vastly outnumber originals, making it almost certain that we are not the originals.

This line of reasoning has drawn attention from scientists as well as technologists. Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson has said he finds it difficult to argue against the hypothesis, putting the odds at “better than fifty-fifty.” Surveys of quantum computing specialists reveal that many take the question seriously enough to explore ways of testing it.

Some physicists suggest that evidence may already be hiding in plain sight. Quantum mechanics shows that matter is pixelated into discrete units, like the building blocks of code. The speed of light could represent a processing limit, akin to the maximum clock speed of a processor. Particles only collapse into definite states when observed — a phenomenon that looks suspiciously like objects rendering only when a player enters the scene. Even “spooky action at a distance,” where entangled particles mirror each other instantly across vast separations, could reflect a deeper computational shortcut.

Experiments have even been proposed. Dr Melvin Vopson at the University of Portsmouth suggests that information is a fifth form of matter with measurable mass. His plan is to annihilate particles and their antiparticles to search for the predicted photon signatures of encoded information. Others suggest monitoring physical constants for sudden shifts, as if the “programmer” were patching errors.

Not everyone is convinced. Many dismiss the hypothesis as philosophy wrapped in science fiction. A perfect simulation, they argue, is indistinguishable from reality by definition, which makes the distinction irrelevant.

Yet the idea remains compelling, not because it may one day be proved, but because it forces us to confront the deepest questions of meaning, purpose and existence. Whether real or rendered, our experiences still matter. And perhaps the most human act of all is to keep asking questions, even about the very stage upon which we play our lives.

AI vs. Human: The Great Water Cup Caper

Taco Bell’s vision of the future was frictionless drive-throughs powered by voice AI. Reality had other plans. One mischievous customer ordered 18,000 water cups, overwhelming the system and forcing a handover to a human server. The stunt went viral, turning a multimillion-dollar technology rollout into an online punchline.

The company admits it is still working out when and where AI makes sense. Its Chief Digital Officer confesses that sometimes the AI impresses, sometimes it fails. His advice to franchisees: use it when it helps, but be ready to jump in when it doesn’t.

The deeper lesson lies beneath the comedy. AI is powerful, but brittle. It thrives on patterns. Humans break patterns. And when faced with ingenuity or mischief, no amount of code can compete with a determined person armed with creativity and time to spare.

The episode may have been a prank, but it highlights a serious truth: in the clash between algorithms and people, humour and unpredictability remain our sharpest advantage.

🚀 Final Thought

Testing the Edges of Reality

From Red Bull’s empire built on prohibition, to physicists daring to test whether the universe is real, to pranksters humbling fast-food AI, the thread is the same. Progress always invites scepticism. Ambition always provokes resistance. And humanity always finds a way to probe, question and laugh.

The lesson is not to fear these challenges but to embrace them. To test the edges, whether of business, science or technology, is how we move forward.

Until next Sunday,

David

David Richards MBE is a technology entrepreneur, educator, and commentator. The Sunday Signal offers weekly insights at the intersection of technology, society, and human potential.

© 2025 David Richards. All rights reserved.