When Heritage Meets Billions: The Week Football, Robots and Davos Reminded Us What Actually Matters

My bid for the world's oldest football club, why humanoid robots will be in our kitchens within the decade, and why Davos remains the world's most expensive exercise - Issue #38 | Sunday, January 25

The Bottom Line Up Front

This week I announced that the group I represent made two bids to buy Sheffield FC. Both rejected. Not because the money isn’t real (it is, measured in hundreds of billions). Not because the vision isn’t compelling (imagine Wrexham, but with actual heritage). But because football’s founding chapter risks becoming a footnote unless someone acts. Meanwhile, Tesla is pricing humanoid robots at the cost of a modest car, and in Davos, David Beckham showed up to promote Bank of America whilst navigating a very public family crisis. One of these stories matters for the next century. The other two just capture this moment rather well.

When the World’s Oldest Football Club Becomes the World’s Most Obvious Opportunity

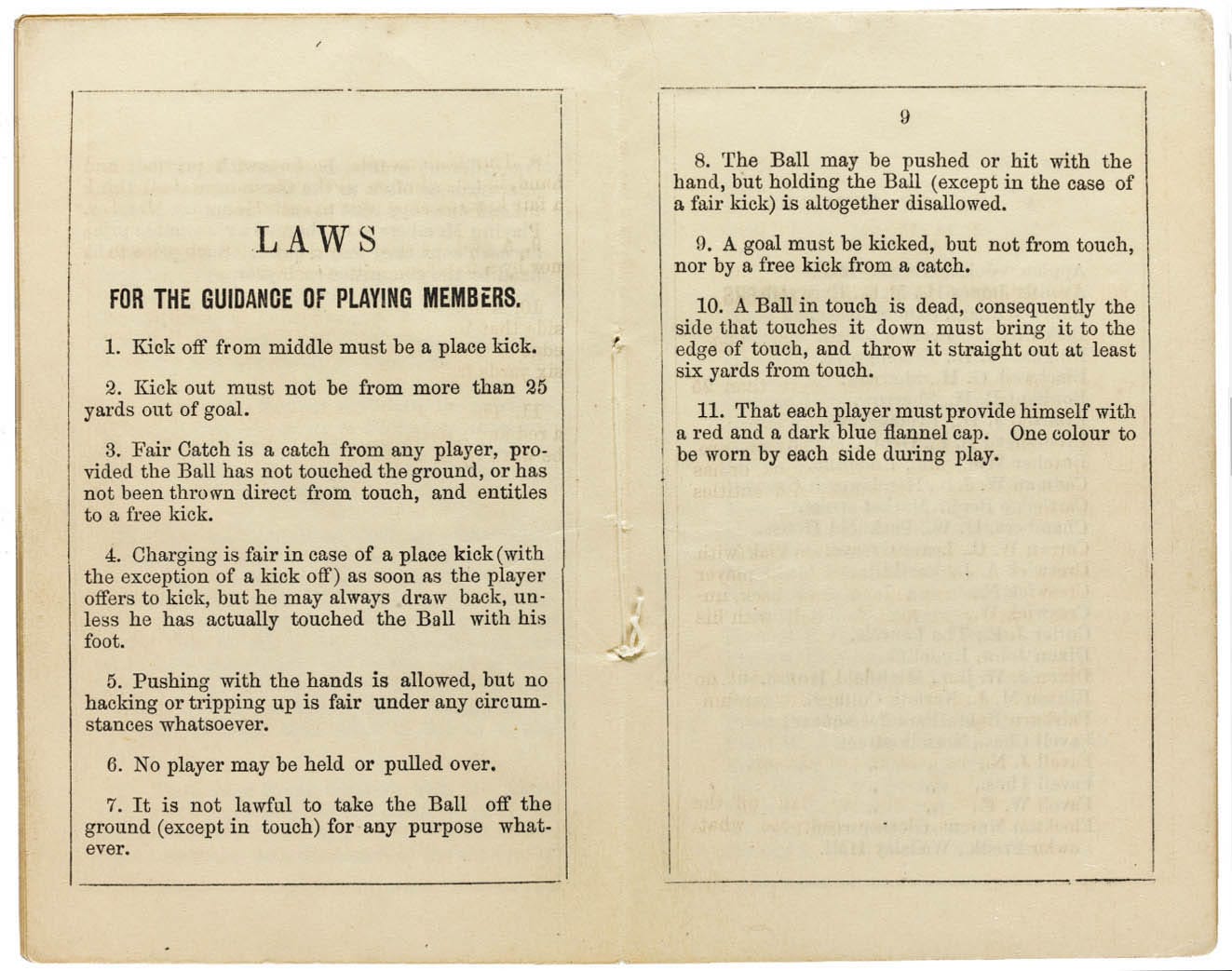

Sheffield invented football. Not metaphorically. Actually invented it.

The rules were written here. The first inter-club match was played here at Sandygate, the world’s oldest football ground, in 1860. The offside rule, the corner kick, the goal kick. Sheffield FC, founded in 1857, is not just the oldest football club in the world. It is the original football club. Every other club on earth is a variation on what started here.

And yet walk through Sheffield city centre and you will find no statue. No museum. No monument. The home of football has let its legacy drift into near obscurity whilst Manchester curates the national museum and Nottingham claims Robin Hood.

So this week, when I announced that Yorkshire AI Labs, the venture capital firm I manage, had submitted two bids to buy Sheffield FC, the story finally became public. We were not trying to buy a club. We were trying to anchor hundreds of billions of dollars of institutional investment into a city region that has forgotten its own crown. Patient capital. The sort deployed into infrastructure and long-lived assets. The sort that builds new 15,000-seater stadiums and world-class ‘Home of Football’ museums. The sort that creates jobs and tourism and regeneration across South Yorkshire for generations.

Both bids were rejected. Discussions have now stalled.

Let me be clear about what this is and is not. This is not about personalities. This is not about football politics. This is about whether Sheffield chooses to properly invest in and protect its status as the home of football, and whether Sheffield FC is treated as the global heritage institution it actually is.

The proposal is live. It has been professionally structured through an FCA-regulated UK investment bank, with independent verification and evidence of funding available under confidentiality. It is backed by a private family office with access to capital measured in the hundreds of billions of dollars. Not speculative money. Not leveraged finance. Not short-term funding. Institutional-scale, patient capital.

For the fund, this would be a small allocation. For Sheffield, it would be transformational.

Three visitors from California came to visit recently and made a beeline for Sandygate. Their reaction? Total amazement. Not at the ground. At the lack of recognition. “Why,” they asked, “is the football museum in Manchester? Why isn’t Sheffield the beating heart of this story?”

If this were the United States, Sheffield would be a pilgrimage site. There would be bronze statues, school trips, and probably a Netflix documentary. Instead, we have let the origin story drift into obscurity, hidden in plain sight.

Sheffielders have never been ones to brag. When Sheffield pioneers drew up the first rules for playing football, their interest was not to stake a claim in the history books, but to create a beautiful game. But we have now taken that modesty too far. Sheffield, which gave the world not just stainless steel but the blueprint for the global game, has let its football legacy fade into the background.

Before Real Madrid, Manchester United, Liverpool and Barcelona, there was Sheffield.

The question now is simple. Whoever owns Sheffield FC must be prepared to invest heavily and for the long term to realise its potential as the world’s oldest football club and as a driver of jobs, tourism and regeneration. If the current owner has a fully funded plan to do that, that is entirely legitimate. What matters is not ownership, but whether the ambition is properly financed.

This is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to anchor serious private investment in the city region using football heritage as the platform. The capital exists today. The interest exists today. The question is whether Sheffield chooses to align with that opportunity, or whether that capital ultimately deploys elsewhere.

Football’s birthplace does not need an ad campaign. It needs a backbone.

From C-3PO to Your Kitchen: Why the Robot Revolution Is No Longer Science Fiction

From my column in this week’s Yorkshire Post

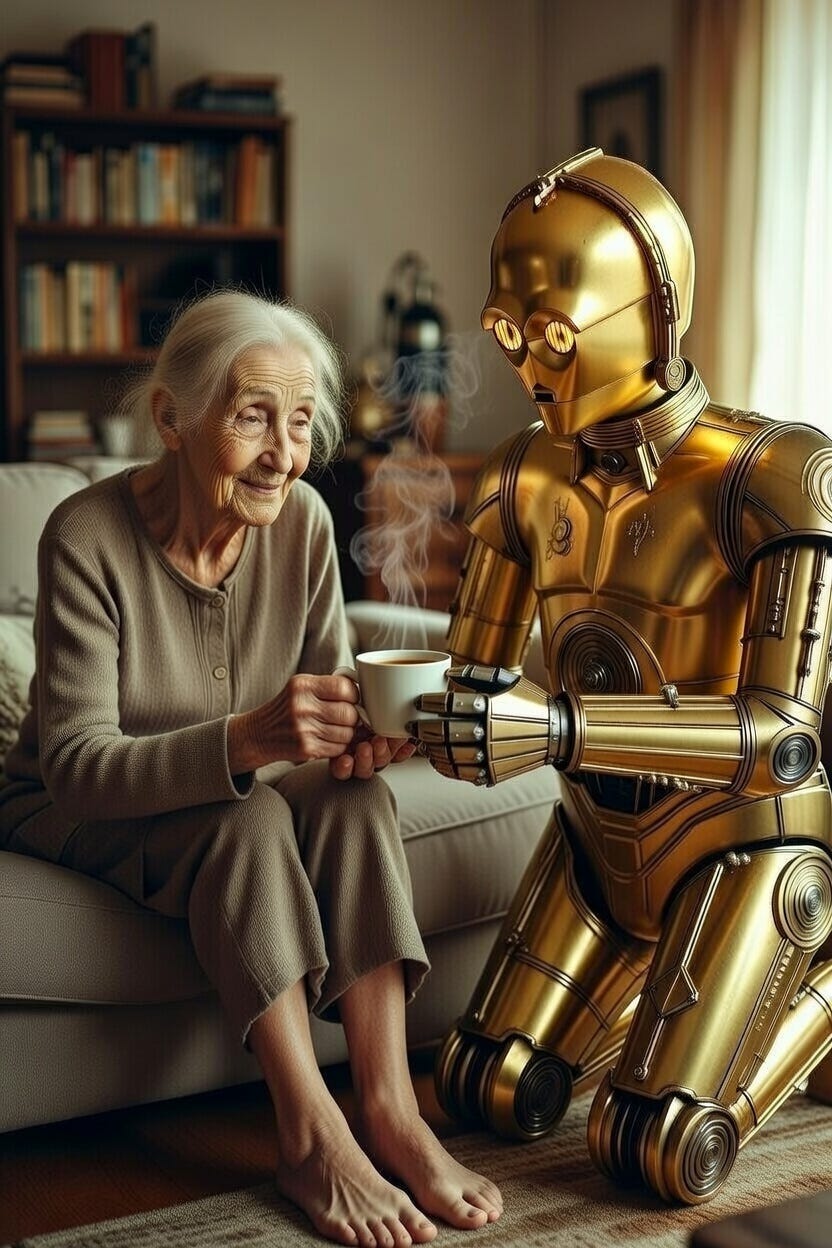

When Star Wars arrived in 1977, C-3PO was charming precisely because he was impossible. A fussy golden protocol droid fluent in six million languages, capable of instant calculation, navigating complex social situations with neurotic precision. It was fantasy.

Fast forward to 2026, and none of that sounds fantastical anymore.

Language models converse fluently across languages. Real-time translation is mundane. Machines routinely outperform humans at probability, logistics and optimisation. The missing piece was never intelligence. It was embodiment. Giving cognition arms, legs and hands that can actually do something useful in the physical world.

That gap is closing faster than most people realise.

Tesla’s humanoid robot, Optimus, can now serve popcorn and pour drinks with an ease that would have seemed absurd even five years ago. The latest generation moves with smooth, almost human fluidity. Tesla has explicitly designed it for domestic work: cooking, cleaning, tidying. Sales are expected to begin later this year at a price between $20,000 and $30,000. Elon Musk is talking openly about producing millions to address global labour shortages.

That price point matters. It puts a humanoid robot in the same mental category as a modest car.

Tesla is hardly alone. Figure AI, backed by OpenAI, Microsoft and NVIDIA, is already testing robots inside BMW factories and has pulled forward home trials to late 2025. Boston Dynamics has retired its hydraulic Atlas in favour of a fully electric version designed for real industrial work. Agility Robotics has its Digit moving boxes in Amazon warehouses. 1X Technologies, also backed by OpenAI, has begun taking pre-orders for a home robot called NEO.

China may be moving even faster. Unitree Robotics is targeting price points as low as $16,000. UBTECH Robotics already has robots piloted inside Nio and BYD factories. China now has more than 100 humanoid robotics firms and leads the world in annual installations. That concentration of effort rarely ends as a sideshow.

The rollout path is becoming clearer. Between now and 2026, we see early adopters hosting alpha and beta units in homes. Limited, supervised, imperfect. By the late 2020s, reliability improves, costs fall, capabilities broaden. Many experts believe that by around 2030, household humanoids will be able to perform unscripted chores without constant oversight. Cleaning a kitchen. Assisting an elderly person. Handling basic repairs.

There are real hurdles. Safety and trust matter profoundly. A robot must be able to read a room and adjust its behaviour around humans. Battery life remains measured in hours, not days. Affordability will initially favour leasing over outright purchase. But none of these are fundamental barriers. They are engineering problems. And engineering problems get solved.

Project forward 10 to 20 years. Picture an 80-year-old living independently at home, not just with a cleaner or a cook, but with what amounts to a 24-hour medical assistant, plumber, electrician and carer. Not average ones either, but systems trained on the collective expertise of the best professionals in the world.

When asked whether you would trust AI to diagnose or treat you, the question may well invert. Why would you rely solely on a human?

The societal implications are vast. Musk talks about a future of universal high income, where goods and services become so cheap that scarcity collapses. Others argue that work becomes optional, something pursued for purpose rather than survival. Some forecasts suggest billions of humanoid robots by 2040, potentially outnumbering humans.

There will be disruption. Jobs will disappear. Human interaction may decline in some sectors. But ageing populations and chronic labour shortages make this transition inevitable rather than optional.

George Lucas created C-3PO as comic relief in a space fantasy. A fussy butler worrying about protocol in the middle of a galactic rebellion. It turns out he was not imagining the future so much as sketching a blueprint for it.

The only real question left is not whether humanoid robots will enter our homes, but how quickly we choose to let them in.

Davos: Still a Stage for the Privileged, Still Not Progress

Every January, the same ritual. My feed fills with posts from Davos. Self-congratulatory photos of “business leaders” networking over fondue, vague declarations about “changing the world,” and a parade of pay-to-play participants all vying for attention.

This year delivered the perfect distillation of why Davos remains less about solving global problems and more about a PR exercise for the ultra-privileged.

David Beckham showed up.

Not to discuss football heritage or grassroots sport. To promote a five-year Bank of America sponsorship deal. He recorded a podcast with popular science author Adam Grant for “Radio Davos” on a series called “Re-thinking,” focused on “resilience, failure, regret and disappointment.” The timing was grimly appropriate. Just hours earlier, his eldest son Brooklyn had posted a six-page Instagram statement accusing his parents of controlling press narratives, prioritising image over intimacy, and trying to ruin his marriage.

When reporters asked Beckham about it, he walked away. Later, in a CNBC interview about children and social media, he offered carefully chosen words about letting kids make mistakes online, knowing every syllable would be read against the backdrop of his own family’s very public tensions.

This is Davos in 2026. A football icon navigating personal crisis whilst promoting banking partnerships on a Swiss mountainside, against a backdrop of over 3,000 high-level participants, 65 heads of state, and 830 CEOs gathering under the theme “A Spirit of Dialogue.”

Meanwhile, Donald Trump threatened tariffs on European nations if they did not sell him Greenland. Denmark declined to attend in protest. Trump’s speech was described by one analyst as “rambling and bullying of his country’s closest allies,” in contrast to Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney’s “eloquent exposition of the dangers of a world where might makes right.”

The location itself feels like an insult. An exclusive Swiss mountain resort, inaccessible to most, extortionately expensive, with attendees forking out tens of thousands just to rub shoulders with a select few. Flights, hotels, event fees. It is a price tag designed to keep the rest of the world out.

How can you have meaningful conversations about inclusion, climate change, or economic inequality whilst sipping champagne in a bubble of affluence?

The “pay-to-play” culture is blatant. If you have the cash, you can slap your logo on a panel or a booth, or call yourself a thought leader for a day. It is a circus of vanity and self-promotion, with many attendees more interested in clout-chasing social media posts than genuine impact. The same faces, the same soundbites, the same lack of tangible outcomes.

The World Economic Forum published its Global Risks Report 2026 before the meeting. Extreme weather events dropped from second down to fourth place in the ranking. Not because they are any less urgent, but because geoeconomic fragmentation and societal polarisation have become more pressing. Yet the conversations in those curated halls feel divorced from the communities where these problems are real and urgent.

Do we need more staged conversations in ski chalets? Or do we need less posturing and more action, rooted in places where the challenges actually exist?

I wrote about Davos last year. Nothing has changed. If anything, the contradictions have sharpened. True leadership is not about attending exclusive gatherings. It is about rolling up your sleeves, addressing uncomfortable truths, and making change happen where it matters.

I, for one, remain done celebrating the Davos echo chamber.

🚀 Final Thought

Sheffield invented football but forgot to tell anyone. Humanoid robots are pricing themselves like family cars. And Davos remains an expensive reminder that networking at altitude rarely translates to progress at ground level.

The thread connecting these three stories? Real transformation happens when capital, capability and heritage align around something that actually matters. Not when celebrities promote banks on mountaintops whilst their families unravel online.

Sheffield has a choice. Robots are coming whether we are ready or not. And Davos will continue exactly as it always has.

The question is which of these we choose to take seriously.

Until next Sunday,

David

David Richards MBE is a technology entrepreneur, educator, and commentator.