The Sunday Signal: Who Really Owns the Future

Issue #35 Tuesday 23 December 2025 This week: the year AI became real, the productivity cost we tolerated, and why football ownership is no longer romantic

The Bottom Line Up Front

2025 was the year several comforting assumptions finally collapsed.

That technological change would arrive gradually.

That infrastructure would somehow keep pace.

That ownership still meant control rather than endurance.

It did not work out that way.

This week’s Signal starts with a look back at the year artificial intelligence stopped being tomorrow, then turns to a very British productivity failure hiding in plain sight, and ends with the hard economics now shaping football ownership.

The common thread is power. Financial, physical, and institutional.

Those who understood the real constraints early are already shaping the future. The rest are discovering that influence is far more expensive to recover later.

2025: The Year AI Stopped Being Tomorrow

2025 will be remembered as the year artificial intelligence moved from laboratory curiosity to economic force. The question is no longer whether AI will reshape work. It is whether Britain will lead that transformation or merely endure it.

January delivered the shock. DeepSeek, a Chinese startup, released R1, a reasoning model that matched OpenAI’s capabilities at a fraction of the cost. Training for six million dollars, not a hundred million. Using weaker chips under Western sanctions. The announcement triggered Nvidia’s largest single-day loss in stock market history, wiping out six hundred billion dollars. China had proved that export controls could not stop innovation. They accelerated it.

The technology itself moved beyond recognition. OpenAI launched GPT-5 in August, followed by GPT-5.1 and GPT-5.2 by December. Each release brought faster reasoning, better coding, and fewer hallucinations. In October came ChatGPT Atlas, a full web browser with AI at its core, threatening Google’s twenty-year search monopoly. The message was clear. The browser wars had returned, but this time the weapon was intelligence, not speed.

The power question became urgent. AI data centres demand electricity on an industrial scale. Britain needs six gigawatts of new capacity by 2030. Yorkshire has the chance to anchor that future through Small Modular Reactors, but only if government stops dithering. China builds baseload power without hesitation. We hold consultations. In California, brand new data centres stood idle because utilities could not supply electricity. Microsoft admitted it had warehouses of GPUs it could not switch on. The constraint was not technology. It was energy.

The job losses arrived quietly. Microsoft cut six thousand roles. Dell shed twelve thousand staff. Meta trimmed five per cent of its workforce. Even software engineers found themselves competing with tools that write code faster and cheaper. Unemployment among computer science graduates rose above seven per cent. The safe career advice of the past decade collapsed in months.

Yet while AI accelerated, old assumptions fell. Real-time translation arrived in AirPods, making the Babel Fish real. Wimbledon removed human line judges entirely. AI solved a ten-year microbiology problem at Imperial College London in forty-eight hours. The research timeline compressed by a factor of eighteen hundred.

The cultural backlash began too. Online trolling was finally treated as violence, with prison sentences handed down. The Luddites are back, and their anger is justified if we ignore the human cost of disruption.

Now Wall Street is waking up. The IPO market, frozen since 2021, is thawing. AI valuations are soaring. Venture capitalists are dusting off their party hats. As Prince might have said, we are about to party like it’s 1999. The critical difference is that this time the technology works and the companies have revenues. Real customers are paying real money for tools that deliver measurable value. The dot-com bubble floated on dreams and eyeballs. This time, the foundations are solid. The question is whether Britain will be dancing or watching from the sidelines.

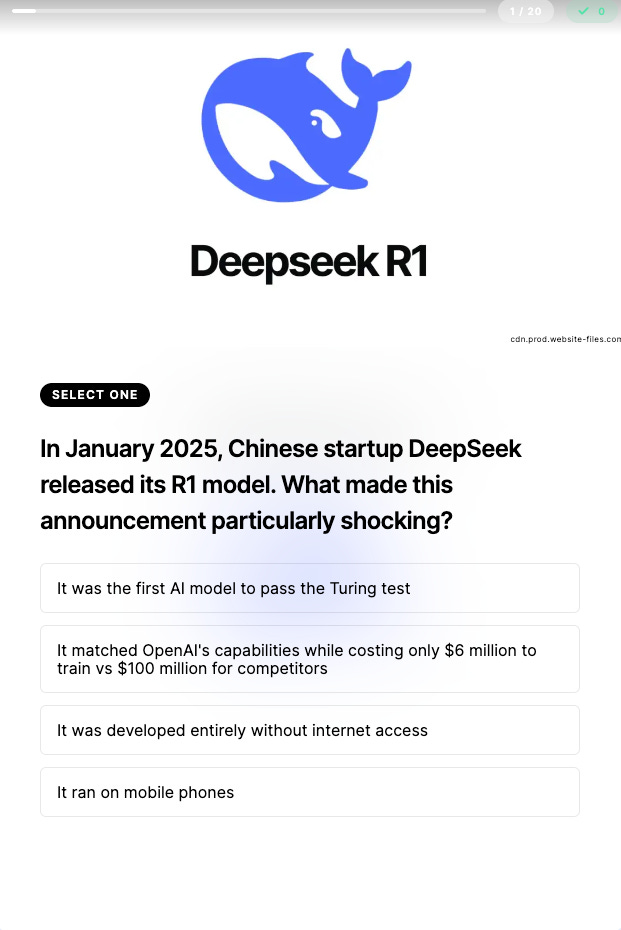

📊 2025 Tech Year in Review Quiz

A short pause before we move on.

Twenty questions. Five minutes. No Googling.

It is designed to test whether you really absorbed what changed this year, or just skimmed the headlines.

The Productivity Cost We Quietly Accepted

My Yorkshire Post column this week focused on something far less glamorous than AI, but just as revealing.

For years, we have paid premium prices to travel between Sheffield and London while being effectively disconnected from the modern economy. Trains designed for a pre-digital age. Signals blocked by their own construction. Onboard Wi-Fi that collapses the moment you try to do anything meaningful.

We argue endlessly about shaving minutes off journey times while ignoring hours of lost productivity inside the carriage.

Last Friday, that finally shifted.

I travelled on one of the new Class 810 Aurora trains and, for the first time on that route, worked properly for almost the entire journey. Not short bursts. Not false hope. Continuous, usable connectivity.

The point is not comfort.

If passengers are paying hundreds of pounds for a return ticket, reliable internet is not a luxury. It is core infrastructure. As fundamental as track, power, and rolling stock.

We tolerated this failure because the cost was diffuse and invisible. In a high-productivity economy, that excuse no longer holds.

Football and the End of Romantic Ownership

This week, the Sheffield Star published my piece on the economics of owning a football club.

Many supporters still imagine ownership as it existed a generation ago. A wealthy local figure. A steady hand. Losses absorbed quietly. The club treated as a civic trust.

That world has gone.

Modern football ownership is not about buying a club. It is about committing to permanent capital injection. The purchase price is often the smallest cheque you will write. Wages are fixed. Revenues are volatile. Infrastructure ages relentlessly. Compliance costs rise regardless of results.

Most wealth is not liquid. Football does not accept net worth as payment. It demands cash, now.

That is why ownership has drifted towards private equity, sovereign capital, and multi-club systems. Not because they care more, but because they can absorb losses without blinking.

Football has become an asset class. Communities are still treating it like a family heirloom.

That mismatch explains much of the anger now aimed at owners. The expectations belong to a different era. The economics do not.

Final Thought

These three stories are not separate.

AI exposed the hard limits of power and energy.

Rail exposed the cost of ignoring productivity.

Football exposed the difference between ownership and endurance.

In each case, sentiment lagged reality.

2025 was the year those gaps became impossible to ignore.

This is the final Sunday Signal of the year. I am taking a short break over Christmas and New Year and will be back on 10 January 2026.

Thank you for reading, replying, and sharing throughout 2025. I hope you have a peaceful Christmas, a restorative break, and a genuinely happy New Year.

The future is no longer theoretical.

See you in January!

A fascinating concise read.