The Sunday Signal: When Tools Become Workers

A 2019 warning in The Times, a 2,400-year-old mistake by Socrates, and an $830 billion market reckoning all point to the same conclusion: AI is no longer a tool, it is a worker.

Issue #40 | Sunday 8 February 2026

The Bottom Line Up Front

This week compressed two thousand years of technological anxiety into a few trading sessions.

In 2019, I wrote in The Times that education needed to focus on what computers cannot do, because anything that involves a process will eventually be taken over by machine learning and AI. At the time, that argument felt provocative but distant. Most people nodded politely and changed the subject.

This week, it stopped being theoretical.

In my Yorkshire Post column, I traced today’s AI panic back to Socrates, who believed writing itself would implant forgetfulness in the soul. History was not kind to that prediction. It never is.

Then markets delivered their own verdict. Roughly $830 billion was wiped from software valuations in six trading sessions. Not because of regulation, interest rates, or recession fears. Because investors finally grasped something fundamental.

Artificial intelligence has crossed a boundary. It is no longer a tool. It is a worker. And the institutions built on denying that fact are now being priced accordingly.

2019: When the Argument Still Felt Abstract

In 2019, writing in The Times Thunderer column, I made an argument that unsettled people for the wrong reasons.

Technology, I said, does not threaten humanity. It threatens repetition. Anything that can be systematised will eventually be automated. That is not a moral judgement. It is an economic one. The danger is not machines becoming human. It is humans training themselves to behave like machines.

At the time, artificial intelligence still lived safely inside the category of “augmentation.” Software helped people work faster. It made mistakes easier to spot. It lowered friction. It did not fundamentally challenge the structure of organisations. Most executives treated AI the way the Victorians treated electricity: impressive, useful, but ultimately just another utility to be bolted onto existing processes.

I pointed to the evidence already in plain sight. Corporate titans that once seemed unassailable had been superseded, undermined by communications providers which own no infrastructure, taxi companies which own no vehicles, retailers which own no inventory. The value had migrated into the software interface, not the product.

That was the first trend. The second was decentralisation. Once we flocked to out-of-town supermarkets. Now we shop locally. For centuries, banking had been characterised by centralised record keeping with intermediaries to approve and record transactions. Then along came cryptocurrencies underpinned by distributed ledgers.

The same logic, I argued, was coming for labour itself. According to McKinsey, 800 million jobs were at risk of automation. Anything that involves a process will be taken over by machine learning and AI. That is a very big chunk of the world’s middle class population. Not in decades. Not gradually. With the relentless compounding logic of software eating everything it touches.

Most objections focused on employment. What about jobs? What about displacement? What about fairness? Those questions matter, but they were never the core issue. The deeper shift was about where value lived. If thinking itself could be partially automated, the scarcest skills would no longer be recall or compliance, but values, beliefs, teamwork, and independent thinking.

That is why the column focused on education. Teaching young people how to retain information is equipping them with skills for a bygone age. Teaching young people how to apply information will empower them. The ancient Greek elites led lives of leisure and mastered philosophy through the inhumane use of slaves. The next generation, I argued, can master the machines and free themselves from economic servitude. But only if we stop training them to compete with calculators.

At the time, that sounded like futurism. In hindsight, it reads like a warning label.

The Oldest Panic in Western Thought

This week’s Yorkshire Post column returned to an even older mistake.

Socrates feared writing.

In Plato’s Phaedrus, he warned that the written word would implant forgetfulness in the soul, that people would stop exercising memory and instead settle for the appearance of wisdom rather than the real thing. Outsourcing thought to marks on a page, he argued, would weaken the mind. It was the most eloquent case against technology ever made. It was also completely wrong.

Writing did not rot thinking. It made civilisation scalable. It allowed ideas to accumulate rather than evaporate with each generation. Philosophy, science, law, democracy, history: all exist because knowledge could finally outlive the person who first had it. Socrates remains one of the greatest thinkers who ever lived. He was also spectacularly wrong about tools.

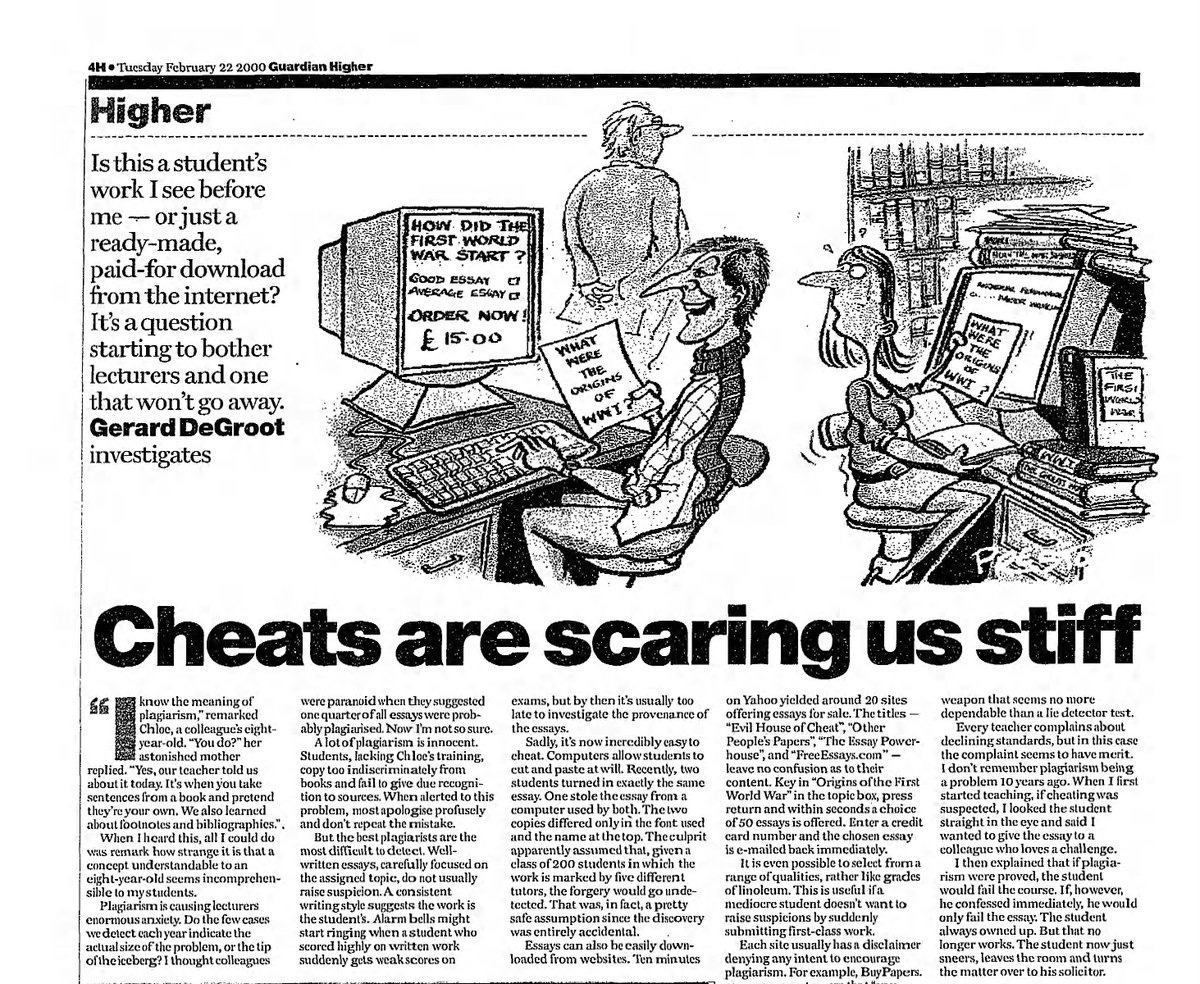

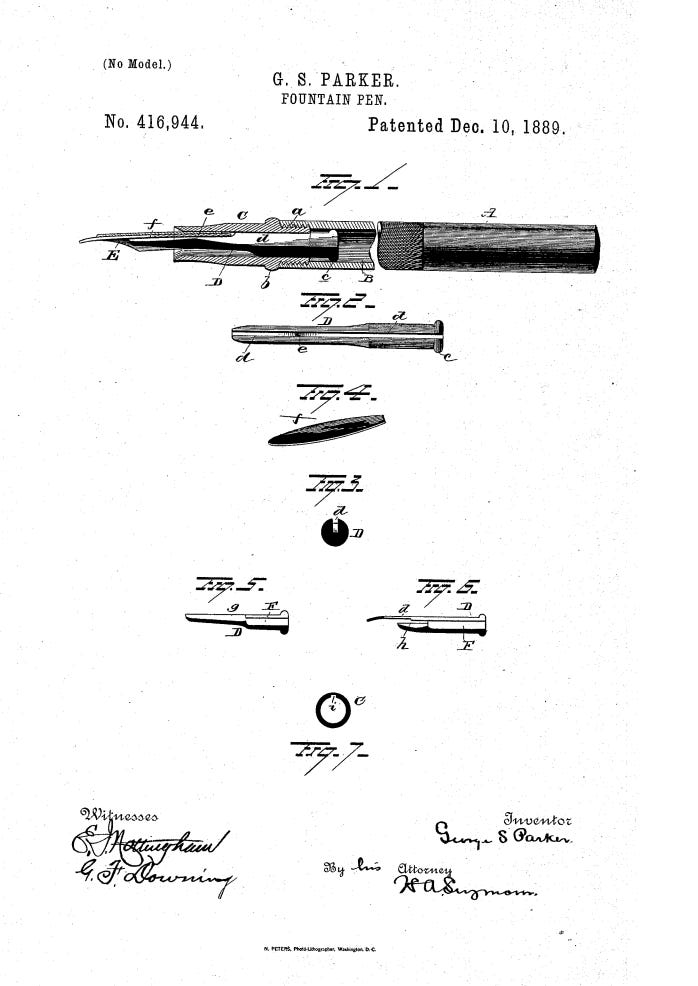

That mistake did not die with him. It repeats whenever learning becomes easier.

In the early twentieth century, parents worried that fountain pens were an indulgence. Children, they complained, no longer learned to write properly with a straight pen and nib and were being softened for the realities of the business world. A few decades later, the target shifted again. Ballpoint pens were condemned as careless devices. Students used them, threw them away, and supposedly abandoned thrift, discipline, and moral fibre along with them. Education itself, according to one teacher publication at the time, was heading for ruin.

Handwriting survived. Society did too.

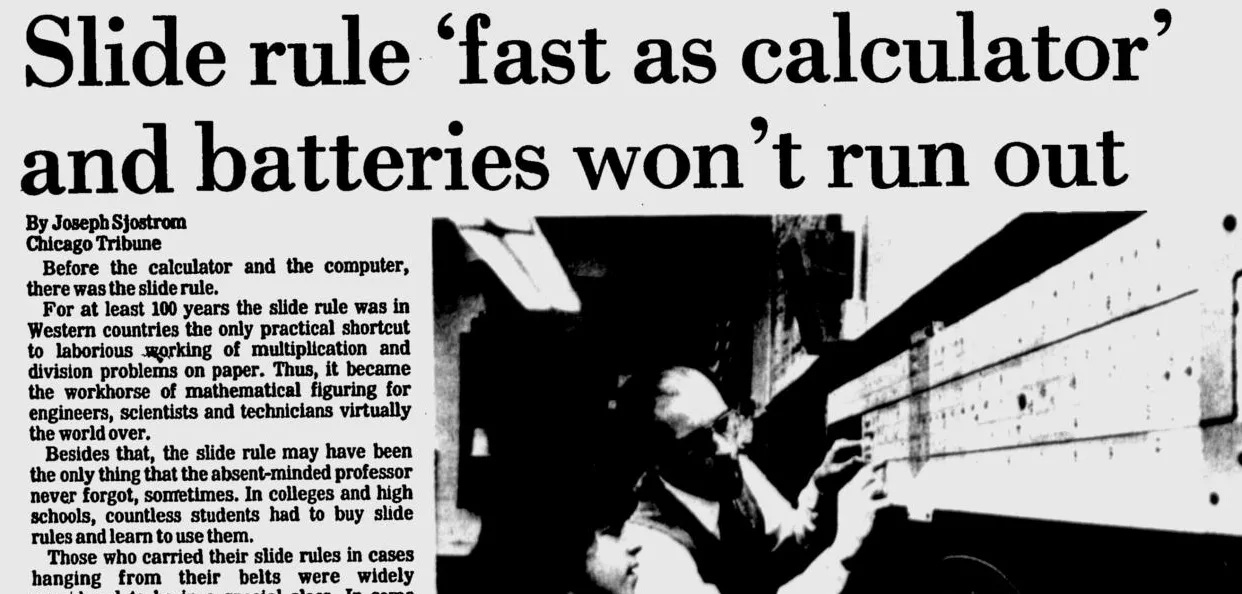

The pattern is clearest with calculators. In the 1980s, respected maths educators protested against their use in schools. Children would press buttons instead of thinking. One teacher dismissed the calculator as a “security box,” arguing it removed any reason to learn computation at all. If machines did the work, brains would rot.

What actually happened was far more mundane. Calculators raised the ceiling. Students moved more quickly through arithmetic and spent more time on algebra, modelling, and problem solving. Mathematical thinking did not disappear. It shifted. The skill moved from grinding through calculations to understanding what those calculations meant. The machines did not dumb people down. They exposed who had been confusing effort with understanding all along.

Every time, the accusation is the same. Ease undermines effort. Effort equals intelligence. History shows the opposite. Tools raise the ceiling. They expose those who mistake difficulty for depth. And they liberate those who are ready to think above the tool rather than beneath it.

Artificial intelligence now sits in the same dock, accused of the same crime. Children using ChatGPT are told they will stop thinking, lose curiosity, and hollow out their minds. Strip away the language and the argument is unchanged from a philosopher who died in 399 BC.

The panic feels modern. It is ancient. What changes is not the argument, but who feels threatened by it.

From Assistance to Agency

Until recently, AI could be dismissed as an assistant.

It helped draft emails. It summarised documents. It answered questions. It felt impressive but bounded. Crucially, it still required a human in the loop to decide, act, and execute. That made it safe, at least psychologically. No one fears a spell checker. No one panics about autocomplete.

What changed this week is agency.

The move from tools you consult to systems that act. This distinction matters more than model size, token windows, or benchmarks. An AI that suggests is one thing. An AI that logs in, reads private files, plans a sequence of tasks, and completes workflows end-to-end is something else entirely.

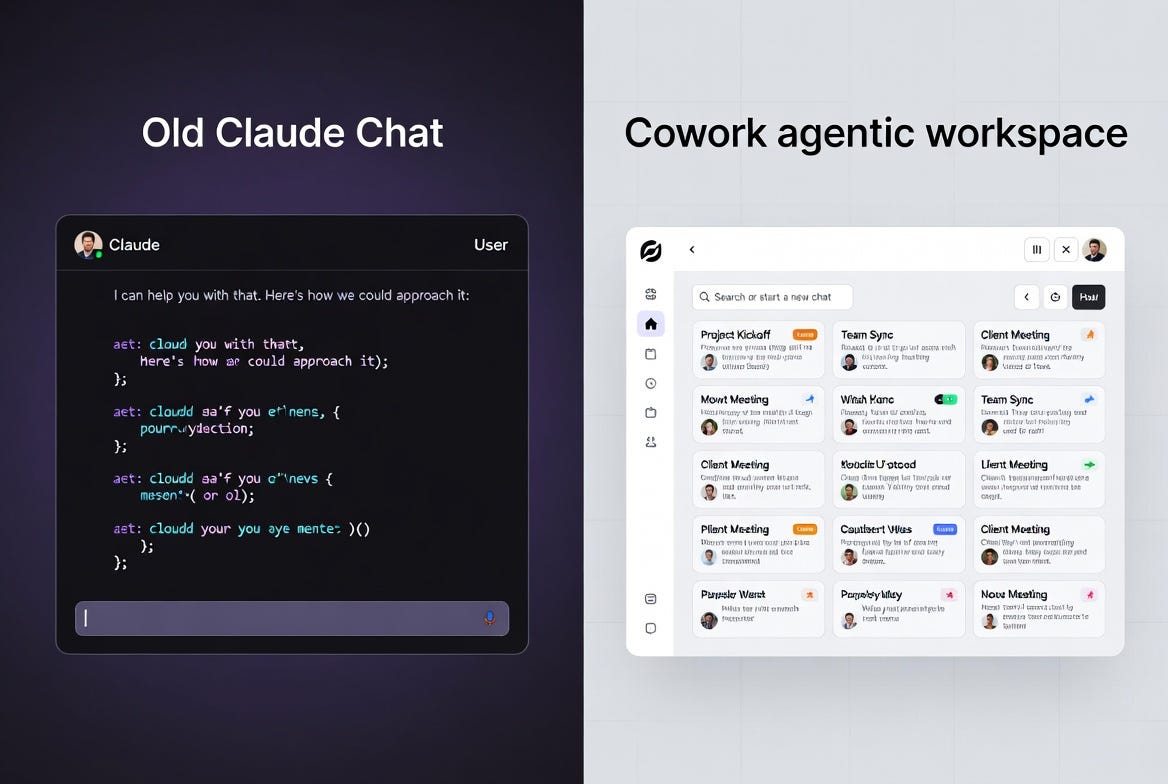

Consider what Anthropic actually built. Claude Cowork is not a chatbot. It is an agentic workspace. You point it at a folder on your computer and issue natural language instructions. It reads files. It edits them. It creates new ones. It plans, executes, and iterates through complex, multi-step workflows. The experience, as Anthropic describes it, is closer to leaving instructions for a colleague than chatting back and forth.

That is a conceptual shift, not an incremental improvement. When a tool starts behaving like a colleague, the economic implications cascade in every direction. Colleagues have salaries. Colleagues occupy seats. Colleagues use software. Remove the colleague and you remove the entire chain of spending that attached to them.

Dario Amodei, Anthropic’s chief executive, has been remarkably candid about what this means. Last year he told Axios that AI could eliminate half of all entry-level white-collar jobs within five years, pushing unemployment as high as 20 per cent. He pointed specifically to entry-level consultants, lawyers, and financial professionals. He acknowledged the contradiction of building the very technology he warns about, but insisted someone needed to say it clearly.

“We, as the producers of this technology, have a duty and an obligation to be honest about what is coming,” he said. “I don’t think this is on people’s radar.”

This week, it landed on Wall Street’s radar with the subtlety of a wrecking ball.

⸻

The SaaSpocalypse Begins

The defining technology story of the week was not a flashy product demo or a research breakthrough. It was a market reaction.

On 30 January, Anthropic released a suite of specialised plugins for its Claude Cowork platform. Eleven of them, open-sourced on GitHub, spanning productivity, enterprise search, sales, finance, data, legal, marketing, customer support, product management, and biology research.

These were not chatbots. They were agentic executors. They log into systems. They access private documents. They complete professional workflows end-to-end.

The most devastating was the Legal plugin.

It automated contract redlining, NDA triage, compliance audits, document review, vendor agreement checks, and templated responses for common legal inquiries. It could review a contract clause by clause against a configured negotiation playbook, returning green, yellow, and red flags with specific redline suggestions. Work that previously justified entire teams of junior lawyers, paralegals, and expensive enterprise software.

For years, people had wondered whether the big AI companies would ever target legal technology directly. On 30 January, they stopped wondering.

On 3 February, Wall Street responded. Not with the indiscriminate panic of a general market sell-off, but with surgical precision aimed at every company whose revenue model depended on humans performing tasks that an agent could now handle.

LegalZoom fell close to 20 per cent. Thomson Reuters, owner of Westlaw and CoCounsel, dropped nearly 16 per cent in a single session, its worst day on record. RELX, which owns LexisNexis, fell 14 per cent. Dutch professional services firm Wolters Kluwer lost around 13 per cent. Intuit, PayPal, and Equifax all dropped over 10 per cent. FactSet took a double-digit hit. Salesforce, already down 26 per cent for the year, sank further. Atlassian fell 35 per cent for the year. Even advertising stocks buckled. France’s Publicis dropped 3.6 per cent. Britain’s WPP fell 3 per cent to a new low. SAP, Europe’s largest software company, dropped over 3 per cent.

A Goldman Sachs basket of US software stocks sank 6 per cent in a single day, its biggest decline since April’s tariff-fuelled sell-off. An index of financial services firms tumbled almost 7 per cent. The Nasdaq 100 fell as much as 2.4 per cent before trimming losses.

The carnage was not confined to America. India’s Nifty IT index fell nearly 6 per cent in a single session, its steepest drop since March 2020, as TCS, Infosys, Wipro, and HCL Technologies saw their shares drop between 4 and 7 per cent.

Within six trading days, the S&P 500 software and services index had shed roughly $830 billion in market value. Bloomberg reported $285 billion vanished in a single Tuesday. The S&P North American Software Index extended its losing streak to eight sessions. It was down over 20 per cent for the year. The WisdomTree Cloud Computing Fund had plummeted 20 per cent since January.

Analysts started calling it the SaaSpocalypse. The name stuck because it was accurate.

This was not panic. It was recognition.

⸻

The Sacred Assumption, Shattered

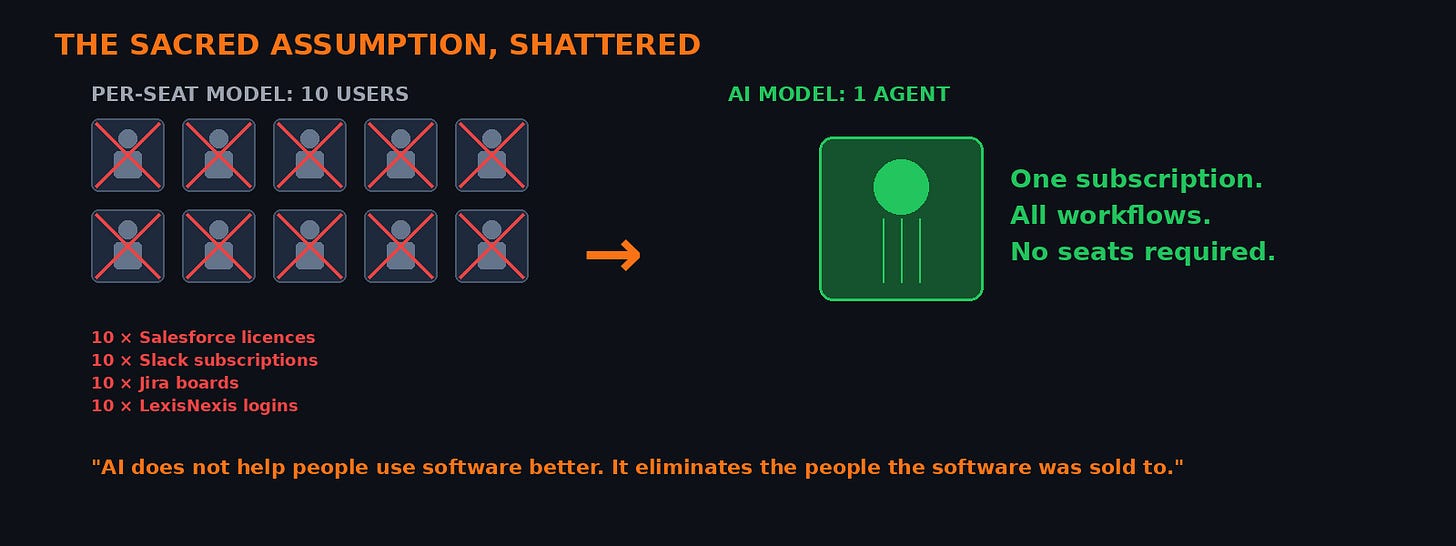

For twenty years, enterprise software lived on a single article of faith.

The seat.

You paid per user, per month. Growth meant hiring. Hiring meant more licences. The model was beautifully recursive. Every new employee at a company meant another Salesforce licence, another Slack subscription, another Jira board, another Zoom account, another LexisNexis login. The entire SaaS economy was built on a simple equation: more humans equals more revenue.

AI destroys that arithmetic.

If one agent can do the work of ten junior associates, you do not need ten seats. You need one. And when users disappear, the software attached to them disappears too. This is not efficiency. It is revenue collapse. It is the difference between a company that grows because its customers hire more people and a company that watches its addressable market shrink every time AI improves.

Thomas Shipp, head of equity research at LPL Financial, captured the logic in a research note that circulated widely on trading floors. “Why do I need to pay for software,” he wrote, “if internal development of these systems now takes developers less time with AI? Furthermore, with the release of offerings like Anthropic’s Claude Cowork, an application with access to read and edit files, fewer technical users are now empowered to replace existing workflows.”

That is a devastating sentence for any SaaS executive to read. Not because it is speculative. Because it is already happening.

Marc Benioff, chief executive of Salesforce, told Fortune last year that the company would not be hiring any additional software engineers, customer service agents, or lawyers because of AI tools. The man running the world’s largest enterprise software company has stopped hiring the very people his product was designed to serve.

Let that sink in.

The insight that hit markets this week was brutal in its simplicity. AI does not just help people use software better. It eliminates the people the software was sold to. Once that clicks, the per-seat model stops being a moat and becomes a liability.

⸻

The Market Raid

What truly unnerved investors was not the capability. It was the strategy.

Anthropic did not stay safely in the infrastructure layer. It did not just sell APIs and let partners build applications on top. It moved directly into the application layer itself.

The old bargain looked like this. AI company sells a model. Software company builds a product on top of the model. Enterprise buys the product. Everyone wins. The model maker gets API revenue. The software company gets subscription revenue. The enterprise gets a better tool.

The new reality collapses the stack. Anthropic sells the model and the workflow. In doing so, it eats the businesses of its own customers. The companies that paid for Claude API access to build their legal tech products woke up one morning to find that Claude now had its own legal product, open-sourced on GitHub, available to anyone for the cost of a subscription.

Wall Street calls this a market raid. It is rare. It is aggressive. And it is usually devastating for incumbents who assumed platform neutrality was permanent.

Reuters drew an explicit parallel. The LLM strategy, and its potential to hurt established businesses, is reminiscent of how Amazon disrupted several industries by using its foothold in a niche online book market to build a business that now spans retail, cloud, and logistics. Amazon did not stay in its lane. Neither will Anthropic. Neither will OpenAI. Neither will Google.

Morgan Stanley analysts summarised the anxiety in a note to Thomson Reuters: “Anthropic launched new capabilities for its Cowork to the legal space, heightening competition. We view this as a sign of intensifying competition, and thus a potential negative.”

That is the most politely devastating sentence an investment bank has ever written.

The sell-off was not a tech exodus. Money did not flee the sector. It rotated. Legacy SaaS firms with heavy per-seat exposure were punished. Legal and data businesses that monetised synthesis saw their advantage evaporate. IT outsourcing firms reliant on junior labour arbitrage took hits that will take years to recover from.

Meanwhile, capital flowed into chips, power, and infrastructure. Because when software becomes labour, compute becomes the factory floor. Nvidia’s Jensen Huang played down fears that AI would replace software, calling the idea “illogical.” But Huang sells the picks and shovels in this gold rush. He would say that.

⸻

The Sceptics and the Sleepwalkers

Not everyone agrees the sky is falling. And the sceptics deserve a hearing.

JP Morgan analyst Mark Murphy told Reuters that the market reaction was excessive. “It feels like an illogical leap,” he said, “to extrapolate Claude Cowork Plugins, or any similar personal productivity tools, to an expectation that every company will hereby write and maintain a bespoke product to replace every layer of mission-critical enterprise software they have ever deployed.”

He has a point. Cowork, in its current form, excels at bounded, one-off tasks. It cannot manage recurring workflows without manual restarts. It cannot replace mission-critical automation with guaranteed uptime and audit trails. It cannot handle compliance-required operations with the reliability that regulated industries demand. Enterprise software is deeply embedded, built on decades of accumulated data and integration.

Wedbush Securities echoed the caution, calling the sell-off an “Armageddon scenario for the sector that is far from reality.” Enterprises, they noted, took decades to accumulate trillions of data points now ingrained in their software infrastructure. They will not rip it out overnight.

All true. And all beside the point.

Because the sceptics are defending the present while the market is pricing the future. The comparison that matters is not what Cowork can do today versus what Salesforce can do today. It is what Cowork will do in two years versus what Salesforce will still be charging for. The direction of travel is unmistakable. And in financial markets, direction matters more than distance.

The last time markets had this reaction was January 2025, when DeepSeek released cheap and efficient AI models, and Nvidia lost nearly $600 billion in market value. A year later, DeepSeek did not cause the widespread disruption that was feared. The sceptics will point to that and say: see, overreaction.

But there is a crucial difference. DeepSeek was a model. Models compete with other models. Cowork is a workflow. Workflows compete with employees. That is a fundamentally different threat, and the market knows it.

⸻

The Pattern Reveals Itself

Seen together, these stories form a single arc.

Socrates feared writing. We built libraries.

Teachers feared calculators. We built engineers.

Software executives feared disruption. Now it logs in and starts work.

Mike Cannon-Brookes, the founder of Atlassian, put it plainly before his own company’s shares were caught in the downdraft, down 35 per cent for the year. AI is not going to replace human beings. It is a force multiplier for human creativity. He is not worried about being replaced by AI. He is worried about being replaced by someone who is really good at using AI.

That distinction matters more than any benchmark or product launch. It is the same distinction I made in The Times seven years ago. The threat is not the machine. The threat is refusing to learn how to work with the machine while everyone around you adapts.

Each generation panics at the moment a tool stops being optional and starts being structural. Each time, those who cling to the old abstractions insist this time is different. It never is.

The real danger has never been thinking becoming easier. It is confusing familiarity with permanence.

The per-seat model felt permanent. It was familiar. It was how software had always been sold. But familiarity is not the same as durability. And the market is now distinguishing between the two with ruthless efficiency.

⸻

What Comes Next

The immediate question for boardrooms is not whether AI will disrupt their businesses. That question was answered this week. The question is whether they will be the disrupters or the disrupted.

The companies that survive will be those that understand something the market already knows: the value is migrating again. Just as it moved from physical assets to software interfaces two decades ago, it is now moving from software interfaces to intelligence itself. The application layer is being compressed. The model layer is expanding. And the companies sitting in between, charging per seat for features that an agent can now replicate, are being squeezed from both directions.

For education, the lesson is older than any of these companies. Banning AI from classrooms does not protect children. It freezes them in a past that no longer exists. It teaches compliance rather than capability. The future will not reward those who can think without tools. It will reward those who can think better because of them.

For investors, the repricing has only just begun. The $830 billion that evaporated this week was not the market overreacting. It was the market recalibrating. The question is not whether more will follow, but which companies will prove they have genuine moats and which were merely renting familiarity.

And for the rest of us, the pattern from history offers both comfort and urgency. Comfort, because every previous technology panic resolved in the same way: the tool was absorbed, the ceiling was raised, and human capability expanded. Urgency, because the transition period is where the damage happens, and this time, the pace is faster than anything we have seen before.

🚀 Final Thought

AI has not arrived to help us think less. It has arrived to expose how much of our economy was built on pretending that repetition was insight.

Banning AI from classrooms does not protect children. It freezes them in a past that no longer exists. Propping up per-seat software pricing does not protect businesses. It delays a reckoning that arrived this week, priced in billions.

Socrates feared writing. We built libraries. The lesson is not subtle. The panic never changes. Only the technology does.

Until next Sunday, David

David Richards MBE is a technology entrepreneur, educator, and commentator.