The Sunday Signal: When to Kill Your Heroes (And When Not To)

Issue #39 | Sunday, 1 February 2026 This week: Tesla’s honourable discharge, why being there still matters, and the real innovator’s dilemma

The Bottom Line Up Front

Elon Musk killed the Model S and Model X this week. Alex Ferguson would recognise the instinct immediately.

The question is whether this is Ferguson-style predictive rebuilding, or something more dangerous: letting go of the present before the future has earned the right to replace it.

This week’s signal is about strategic ruthlessness, the human cost of optimisation, and why the hardest innovations to spot are often the ones that make us more human, not less.

Sell at the Peak (The Ferguson Playbook)

On Tesla’s Q4 2025 earnings call, Elon Musk announced the Model S and Model X will receive what he called an “honourable discharge”. Production winds down next quarter. The factory space at Fremont that built them will be stripped out and repurposed for Optimus humanoid robots, with a long-term target of one million units per year.

If you want a new Model S or X, the message was blunt. Order now.

This matters because the Model S did not just sell cars. It changed belief. It proved electric vehicles could be fast, elegant and desirable. It won MotorTrend Car of the Year in 2013, the first EV ever to do so. Tesla does not exist in its current form without that car.

Now it is being retired. Not because it failed. Because it is in the way.

This is pure Alex Ferguson.

In The 90-Minute Manager (a great read and written by my friend, Chris Brady), Ferguson’s career is reduced to one uncomfortable truth: the hardest time to rebuild is when things are going well. His answer was predictive rebuilding. Sell players not when they decline, but when they peak. A year too early, not a year too late.

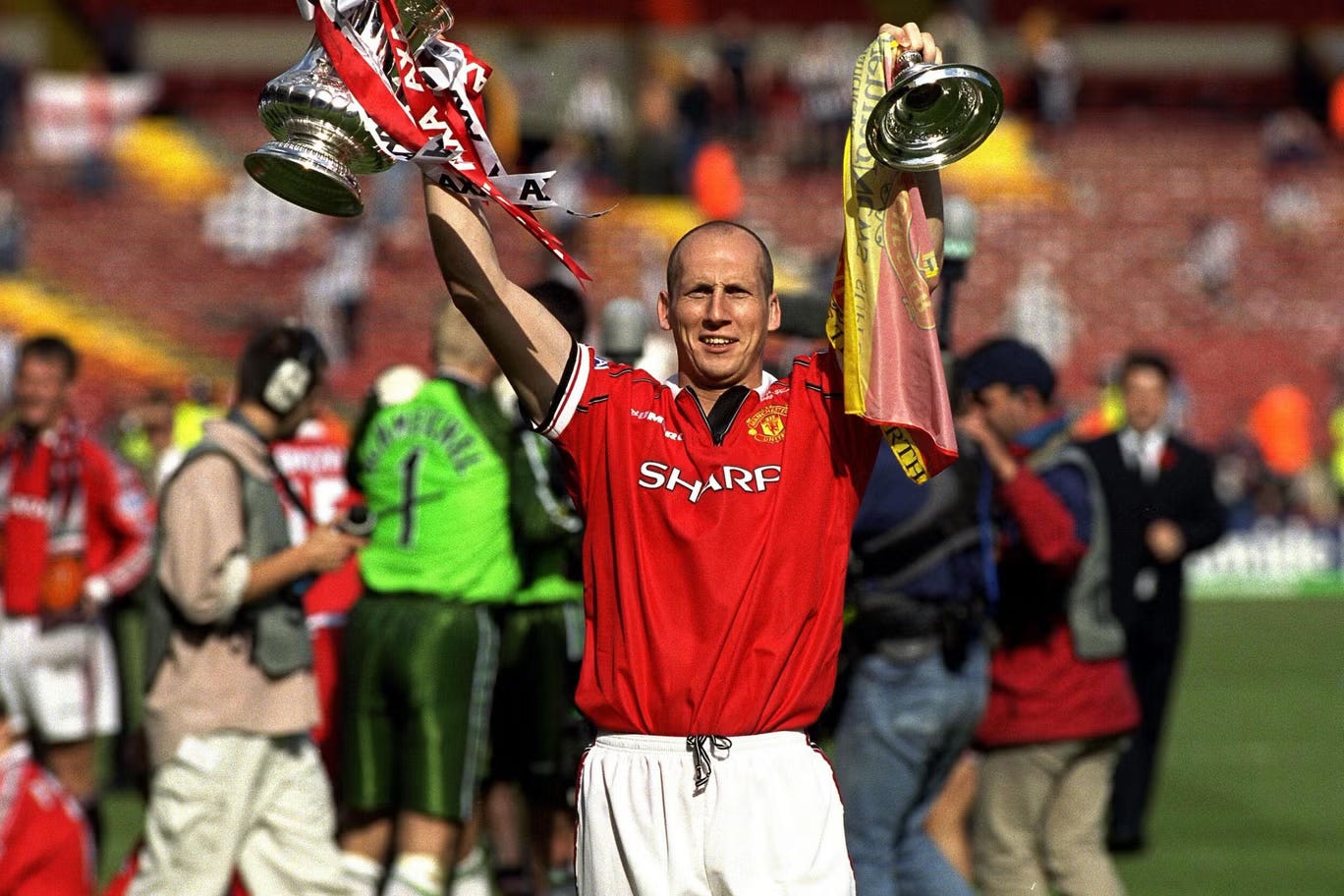

Jaap Stam is the canonical example. In 2001, he was 29, dominant, feared, widely regarded as the best centre-back in the world. Ferguson sold him anyway, reportedly for £16.5 million. Stam was told at a petrol station. Within 24 hours, he was in Rome.

David Beckham followed. A global icon at 28, creative engine, commercial supernova. Ferguson sold him to Real Madrid for €35 million. The reason was not footballing decline. It was gravity. Beckham was becoming bigger than the system. Ferguson immediately signed an 18-year-old Cristiano Ronaldo and reset the cycle.

Then Ruud van Nistelrooy. Goals in abundance, but the team was starting to calcify around him. Too predictable. Too static. Ferguson moved him on to make room for a more fluid, faster attack.

Even Ronaldo himself was sold at the absolute peak. The reigning Ballon d’Or winner left for a world-record £80 million. Ferguson had extracted maximum value and refused to manage a disgruntled superstar.

The logic was ruthless but consistent. The system is the star. Hold on to yesterday’s heroes too long and tomorrow never gets built.

Tesla is making the same claim.

The parallel runs deeper than most people realise.

The Model S is Jaap Stam. Authority. Credibility. Proof that Tesla belonged at the top table. But built for a phase of the game that is ending.

The Model X is Beckham. Technically impressive, culturally iconic, slightly over-engineered, and increasingly defined by spectacle as much as necessity.

Model 3 and Model Y are the system players. Relentless. Repeatable. Fit for the modern game. They do not grab headlines, but they win the league.

And Optimus is not a replacement signing. It is a formation change.

Ferguson did not sell stars to buy better stars. He sold stars to change how the team played. Musk is claiming to do the same. He is not upgrading the car. He is betting the future is no longer a car game at all.

The numbers explain the brutality. In 2025, Tesla delivered around 1.64 million vehicles. Fewer than 51,000 were Model S or X. The flagship cars had become rounding errors.

Tesla also reported its first annual revenue decline, roughly 3 per cent. Margins are thinning. Chinese competitors like BYD are relentless. Maintaining two complex, low-volume luxury platforms no longer makes strategic sense.

So Musk is reallocating capital. Tesla plans to push capital expenditure beyond $20 billion in 2026, and that money is not going into better cars. It is going into AI compute, autonomy and robotics.

Musk no longer describes Tesla as a car company. He calls it a physical AI company.

This is not Kodak.

Kodak invented the digital camera in 1975 and buried it. Film was beautiful. Chemical. High margin. Their factories were temples to an old world. Pivoting meant admitting those temples were stranded assets. So they stayed sentimental and protected the past.

Tesla is doing the opposite. Musk is tearing out the production lines of the products that saved him to fund technologies that currently generate little to no proven revenue.

That takes nerve.

The question is whether it also takes insight.

What The Traitors Tells Us About Being There

A few years ago, I travelled on the Orient Express from Paris to Venice. Late one evening in the bar, I got talking to a man who turned out to be a television producer. His show was Love Island.

I had barely watched it. What he explained mattered more than the programme itself.

Love Island, he said, was one of the few shows young people still watched live. Not later. Not clipped. Live, together, at the same time. In an on-demand world, that single fact changes the economics. Advertisers pay more for attention they know exists in a specific moment.

It captured something bigger than television.

I grew up with three channels. BBC1, BBC2, ITV. When Channel 4 launched, it felt like an event. We watched the same things and talked about them the next day. School. Work. The pub. Shared reference points arrived without effort.

Streaming dismantled that. We still watch plenty, but alone, at different times, in different orders. Outside sport and news, collective audiences faded.

Which is why I surprised myself recently by watching The Traitors live on BBC One.

The next morning it was everywhere. Offices. WhatsApp. Half-heard conversations over coffee. People arguing about who would be banished or murdered. Whether Stephen was foolish to trust Rachel. Who cracked? Who overplayed their hand? Who lied just a little too convincingly?

It felt familiar. Not because the programme itself was extraordinary, but because it dragged us back into the same moment.

When millions of people watch the same thing together, it stops being content. It becomes common ground.

And it made me think about work.

COVID proved that remote work is possible. But it also warped our assumptions about presence.

Hybrid works brilliantly for experienced people with judgment and networks already formed. Flexibility often improves life.

For people at the start of their careers, something vital goes missing.

The most valuable lessons I learned early on were not taught. They came from proximity. From watching how difficult conversations were handled. From seeing bad news delivered without burning bridges. Sometimes it was as simple as someone leaning over and saying, quietly, there’s an easier way to do that. Sometimes it came later, over a pint, when the real explanations emerged.

You cannot schedule that learning. You cannot formalise it. Remove proximity and you lose quiet mentoring, early correction and confidence before mistakes harden into habits.

Later that night on the Orient Express, we were the last two people left in the bar. It is a long train, and after a few of the Orient Express’s speciality cocktails, every carriage looks the same. It took us quite a while to find our sleeper cabins.

No agenda. No purpose. Just two people talking because they were there at the same time.

Some things only happen like that. You cannot replay them later. And you only notice what they were doing for you once they are gone.

Sometimes progress is not convenience. Sometimes it is simply turning up, together, and being there.

The Real Innovator’s Dilemma (And Why Tesla Might Get It Wrong)

Clayton Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma explains why great companies fail while doing everything “right”. They listen to their best customers. They optimise profitable products. And that blinds them to disruptions that start small and end up owning the market.

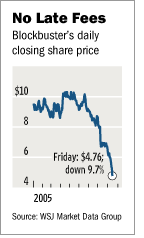

Blockbuster is the classic modern case. Late fees were lucrative, but they were also what customers hated most. In 2000, they accounted for roughly $800 million, about 16 per cent of revenue. Removing them meant killing profit.

Netflix removed them anyway.

Then Netflix disrupted itself. The Qwikster split was a fiasco. Customers revolted. Roughly 800,000 subscribers left in a single quarter, and the stock collapsed. The execution was clumsy. The direction was right.

Then originals. When Netflix spent $100 million on House of Cards, the industry laughed. It looked like vanity. It was actually pre-emptive control of destiny before studios reclaimed their libraries.

Apple did the same thing in 2007. The iPhone did not protect the iPod. It killed it.

So where does Tesla sit?

On the surface, Musk is doing exactly what the playbook demands. He is abandoning low-volume complexity. He is reallocating capital before the market forces him to. He is willing to cannibalise icons.

But Christensen’s dilemma is not solved by ruthlessness alone.

It is solved by being right about what customers will value next.

Netflix won because customers wanted control. Apple won because customers wanted convergence. The disruption worked because it moved toward a real human desire.

So what is Musk betting on?

He is betting that the next mass market is robots and autonomy. That Optimus will scale from demo to deployment. That robotaxis will materially reduce the need for car ownership. That physical AI is not just possible, but wanted.

Maybe he is right.

But there is a difference between a technology being possible and a market being ready. Robotics has a long history of breathtaking demos followed by slow adoption, messy edge cases and unforgiving economics.

Tesla is converting a functioning production footprint into a bet that does not yet have a proven demand curve, a mature supply chain or a stable regulatory runway.

If Musk is right, this week will be remembered as the moment Tesla stopped being a car company and became something much bigger.

If he is wrong, it will not be because he lacked courage.

It will be because he misread what customers actually want, and let go of a functioning product before the future was ready to pay for it.

Ferguson sold a year early rather than a year too late.

Musk is betting he can do the same.

🚀 Final Thought

The Innovator’s Dilemma teaches us that survival belongs to companies willing to disrupt themselves before the market does it for them. But timing is everything.

Ferguson’s genius was knowing when the peak had peaked.

Musk is betting that the Model S and Model X are yesterday’s trophies, and that robots are tomorrow’s league title.

The difference between visionary and reckless is usually only clear in hindsight.

Until next Sunday,

David

David Richards MBE is a technology entrepreneur, educator, and commentator.