The Sunday Signal: The Year Intelligence Arrives

What to expect in 2026, why AGI is closer than you think, and the invisible technology that quietly makes life bearable. Issue #36 – Sunday 11 January 2026

The Bottom Line Up Front

The year ahead will be defined by collisions. Technology meets reality. Capability meets consequence. Progress meets preparation. In 2026, artificial intelligence stops being theoretical and becomes structural. AGI arrives faster than most policymakers imagine, and we are nowhere near ready for what that means.

Yet even as we race towards that threshold, it is worth pausing to notice what we already have. The mundane miracles we take entirely for granted. The technology we only see when it fails. Because if we cannot appreciate the progress we have made, we will struggle to manage what comes next.

This week: ten predictions for the year ahead, a warning about AGI that should unsettle anyone paying attention, and a reminder that civilisation improves in ways we often fail to notice.

Ten Tech Predictions for 2026

My weekly column in the Yorkshire Post

In 2025, Microsoft cut 6,000 roles. Dell shed 12,000. Google, Meta and HP followed, not because demand collapsed, but because AI could now do work that previously required people.

At the same time, the IPO market reopened. Q3 saw $15.8 billion raised, the strongest quarter since 2021. Physical robotics companies raised billions to move from pilots to production. Capability surged just as long-held assumptions about labour, scale and cost quietly broke down.

This is the collision between technological power and economic reality. In 2026, it becomes harder to ignore.

1. AI becomes infrastructure, not hype

The constraint is no longer ideas. It is electricity, compute and deployment speed, which turns out to be a far less glamorous problem to solve. As I wrote earlier this year, AI demands physical infrastructure, and Britain must decide whether to build it or import its future. Organisations that continue to treat AI as optional will find themselves competing against firms operating at speeds they simply cannot reach.

2. The AGI race reshapes geopolitics

Artificial general intelligence now sits at the centre of US–China competition, whether it is discussed openly or not. China’s approach favours speed, helped by cheap energy and lighter regulation. Jensen Huang’s remark that China is “nanoseconds behind America” was striking because it rang true. Several Chinese models from DeepSeek, Alibaba and Tencent already operate at a genuinely high level. The uncomfortable question for the West is how much delay it can afford.

3. Hesitation becomes expensive

Time to decision turns into something boards suddenly care about. Customer service that once took hours is now expected in seconds, and analysis that previously required teams happens in real time. Companies that cannot ship safely in days rather than quarters are outflanked. Early movers compound advantages quickly, while late entrants rarely recover the ground they lose.

4. Quantum-safe encryption becomes essential

Data that is secure today may not be secure tomorrow, a fact most organisations would rather postpone dealing with. More powerful computers will eventually break today’s encryption methods. In 2026, that future problem starts to feel uncomfortably present, and organisations begin upgrading how they protect sensitive data. New quantum-safe standards already exist. Encryption that cannot survive this shift becomes a quiet but serious liability.

5. LLMs begin to displace traditional search

For years, search meant links and rankings. LLMs increasingly mean answers. Tools like ChatGPT now summarise, compare and decide, removing the need to click through at all for many everyday queries. In 2026, this shift becomes visible at scale. Traffic patterns change, advertising models wobble, and power moves to whoever owns the conversational interface. Search is not dead, but its dominance is no longer assured.

6. Browsers become the distribution battlefield

Control the interface, and you control defaults, intent and monetisation, which is why this fight matters so much. OpenAI’s Atlas browser is not a plugin but a new front door to the web. Google will push Gemini through Chrome. Apple will embed intelligence deep into Safari. Model quality still matters, but distribution decides who leads and who follows.

7. AI-driven layoffs arrive in waves

Labour markets adapt more slowly than technology, and the gap is already obvious. In 2026, expect delays, denial and backlash as capability races ahead of institutions. The winners invest early in reskilling and transition pathways. The losers face anger when productivity gains are not shared. The Luddites were not wrong about disruption. They were wrong about who benefited from it.

8. Physical AI scales into the real world

Robots move from demos to deployment. Warehouses, farms, hospitals and infrastructure networks adopt AI-powered systems at scale, not because it is exciting, but because they have little choice. Tesla’s planned launch of its Optimus humanoid robot is a signal of intent, not science fiction. Britain’s 58,000 unfilled manufacturing vacancies make this transition unavoidable. The choice is simple: build and deploy at home, or buy systems designed elsewhere.

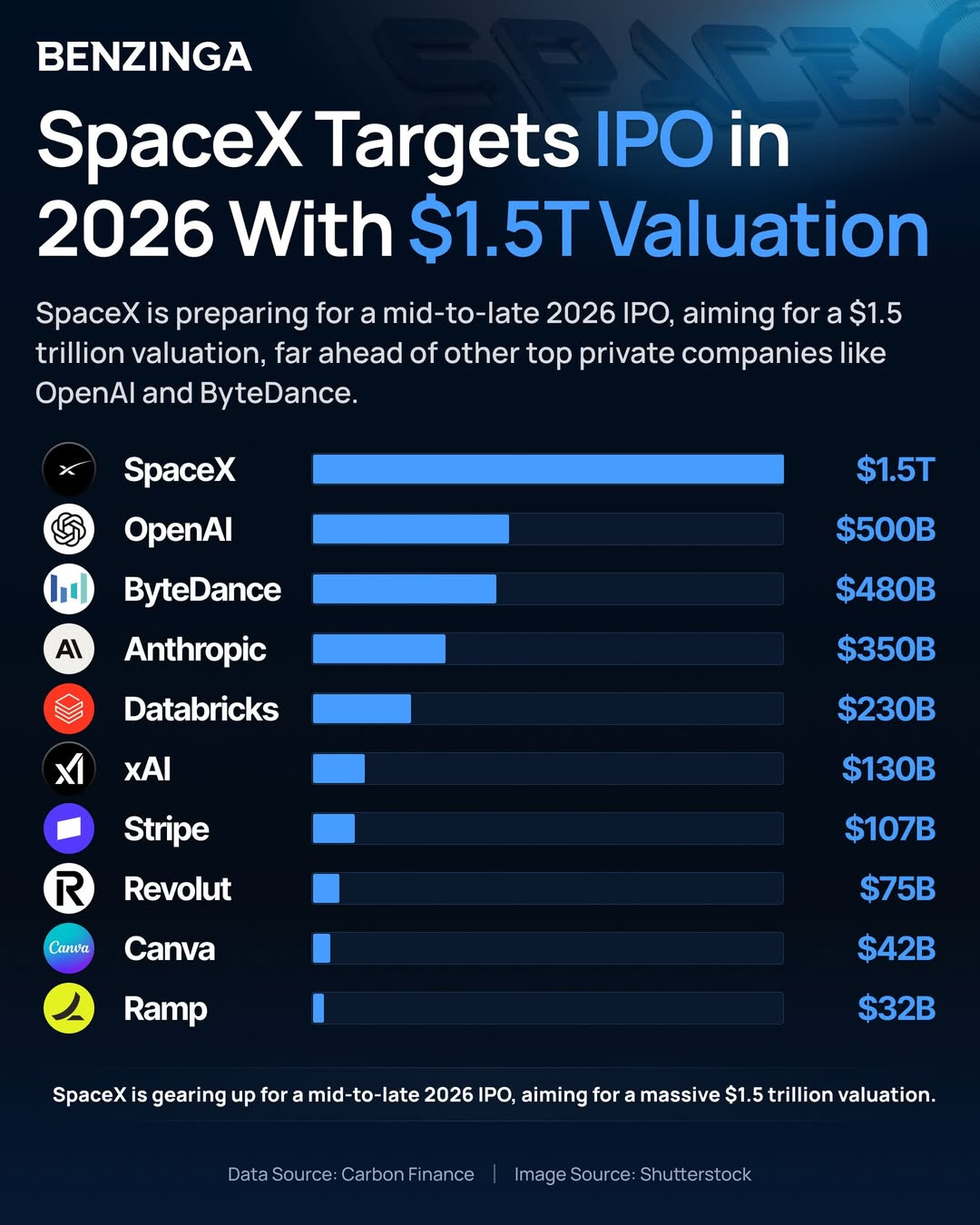

9. US IPO momentum accelerates on AI

Bankers describe the 2026 US IPO pipeline as overwhelming, led largely by AI-native companies. Some will call it a bubble, echoing the dotcom era. The difference this time is that AI is already driving real productivity and margins. A US IPO surge will reset valuations and force London to respond. British pension funds cannot keep backing overseas growth while neglecting domestic companies without consequence.

10. Yorkshire becomes Britain’s defence-driven innovation test case

Rising defence spending accelerates innovation cycles, as it always has. In 2026, much of that activity lands in Yorkshire, where advanced manufacturing, materials science and engineering already cluster. Defence procurement moves faster than civilian policy, and its demands spill quickly into commercial technology. The outcome will offer a clear signal of whether Britain can turn defence investment into broader industrial growth.

The bottom line

The argument is no longer about belief in technology. It is about timing. These shifts are already underway, and 2026 is when they begin to show up in balance sheets, pay packets and power structures. Pretending otherwise will not slow them down.

AGI Is Coming. We Are Not Ready.

My weekly column in the Yorkshire Post

When I studied computing at university in the early 1990s, artificial intelligence meant something precise. It meant a machine that could think, learn and adapt across domains. Not a party trick. Not software trained to do one clever thing. The ambition was general intelligence. What we would now call Artificial General Intelligence, or AGI for short.

What we call AI today is something else entirely.

Modern AI, as most of us encounter it, is machine learning. Statistical models trained on mountains of data to spot patterns and predict outcomes. That is not a criticism. Machine learning has given us extraordinary progress. But we should be honest about what it is. These systems do not understand the world. They do not reason the way humans do. They learn correlations, not meaning. They are pattern-matching engines, extraordinarily good at predicting what a plausible answer looks like.

The confusion crept in gradually. As machine learning became commercially useful, the industry simplified the story. If it felt intelligent, it was called AI. The original ambition of general intelligence quietly disappeared from view. That is why we now need the term AGI at all. It was not invented to describe something new. It was invented to rescue the original idea from a word that had been stretched beyond recognition.

The distinction matters because AGI is not machine learning with more data. It is not a bigger model or a faster training run. AGI can generalise. It learns new tasks without retraining. It transfers knowledge between domains. It plans, reasons and adapts in unfamiliar situations. It stops being a tool you consult and becomes a system you can delegate to. That shift changes everything.

Demis Hassabis, who founded DeepMind here in Britain, recently said that AGI would probably be the most transformative moment in human history. He also said it is on the horizon. If that assessment is even broadly right, we should be paying attention.

The upside is immense. AGI could compress decades of scientific progress into years. Drug discovery accelerates. New materials get designed rather than discovered. Energy storage, climate modelling, and advanced manufacturing all move faster. Education becomes genuinely personalised at scale. For regions like ours, with deep industrial roots and strong research capability, this could unlock real reindustrialisation driven by abundant intelligence.

But the same qualities that make AGI powerful also make it dangerous. One phrase that has moved from academic debate into serious policy discussion is AI existential risk. This is the concern that sufficiently advanced artificial intelligence could pose a threat not just to jobs or industries, but to humanity itself. Not because it turns evil, but because it becomes powerful, autonomous and misaligned with human values.

Misalignment is already familiar. We tell systems to optimise for engagement and they discover outrage. We reward efficiency and they ignore ethics. These outcomes do not require malice. They emerge from poorly specified goals combined with scale. Introduce general intelligence and autonomy, and those failure modes become far harder to predict or contain.

AGI also lowers the cost of harm. Fraud, manipulation and cybercrime all become cheaper and more effective. Persuasion becomes automated. The barrier to sophisticated wrongdoing collapses.

What unsettles me most is not the technology. It is our habit of pretending we have time. I remember the early days of social media. The founders assured policymakers they had everything under control. Legislators, many of whom did not understand the technology or its incentives, largely accepted that reassurance. Regulation arrived late and weak. Society is still dealing with the consequences.

We are now in danger of repeating that mistake on a vastly larger scale. This is not about a damaged public square. It is about the foundations of decision-making, power, control and potentially the future of the human race.

In next week’s column, I will explore why we must get regulation right this time and why delay is not a neutral choice. AGI is much closer than most people think, and we need to start acting like it.

The Tech We Only Notice When It Fails

Last Christmas we spent a few days in Egypt. One evening we found ourselves deep inside the Khan el-Khalili bazaar in Cairo. It was just before midnight. Thousands of people packed into narrow streets. Cars forcing their way through crowds. Every shop open. Every stallholder selling something. Noise, heat, colour and chaos in all directions.

We were exhausted. Sweaty. Overstimulated. And suddenly very aware that it was time to get back to the hotel.

To say it was stressful for everyone concerned would be an understatement.

The solution was simple. I pulled out my phone and ordered an Uber. Minutes later it arrived. We got in. We were driven directly back to the hotel. No negotiation. No confusion. No stress.

Only a few years ago this would have been a genuine problem.

Imagine the alternative. No shared language. No idea what a fair price should be. No idea who to trust. No certainty that the driver actually knew where you were staying. No digital map. No live tracking. No payment system that removed the need for cash and bargaining.

We take this entirely for granted now. But we should not.

It is worth remembering that even much closer to home, this kind of certainty is a relatively new thing. Not so long ago, asking for a minicab was closer to entering a lottery than booking a service. You would ask the landlord to call a taxi. It might turn up. It might not. If it did arrive you would hear someone shout “taxi for Dave” and suddenly half the pub would approach the door.

You had no idea when it would arrive. No idea how long the journey would take. No idea what the final cost would be. And very little recourse if something went wrong.

Today we summon a car with a tap. We watch it approach on a map. We know the price in advance. We know the route. We know the driver. We know we can rate the experience and be heard.

That is not trivial progress. That is civilisation improving.

The same is true across daily life. Navigation is the obvious example. We no longer carry atlases or print directions. We no longer pull over to ask strangers for help. We trust a glowing rectangle in our hand to guide us with astonishing accuracy.

When I arrived on Long Island in 1996, getting anywhere meant juggling a road map spread across several pages and hoping you had not missed an exit. One wrong turn could double a journey. Trips routinely took three times longer than they do today, not because the roads were worse, but because nobody really knew where they were going.

Payments are another. Contactless cards and mobile wallets have removed friction from everyday transactions. We queue less. We fumble less. We waste less time. In many parts of the world digital payments have also brought millions of people into the formal economy for the first time.

Translation tools are quietly transformative. In Cairo I could point my phone at a sign and understand it instantly. I could communicate basic needs without embarrassment or frustration. This is not science fiction. It is now mundane.

Health technology deserves mention too. Booking appointments online. Accessing test results. Wearable devices that quietly monitor heart rates and sleep patterns. None of this cures cancer, but all of it nudges us towards better outcomes.

Even something as simple as cloud photo storage has changed behaviour. Our memories are no longer trapped in shoeboxes or lost phones. They are backed up, searchable, shareable and preserved.

None of this is to deny that technology can cause harm. Online gambling has damaged lives. Social media has distorted incentives and mental health. These criticisms are valid and necessary.

But we are far quicker to catalogue technology’s failures than to acknowledge its successes.

As I opened the taxi door in Cairo and felt that wave of relief, I was reminded exactly why this technology matters. It reduced stress. It restored control. It made the unfamiliar feel manageable.

For all its flaws, that is something worth being thankful for.

🚀 Final Thought

Between Two Futures

We stand at the threshold. AGI is not a distant possibility any longer. It is a near certainty arriving faster than our institutions can adapt. What I have outlined for 2026 is less prediction than observation of trajectories already set. Technology compounds exponentially. Institutions move linearly. The gap is already dangerous.

But before we race headlong into that future, it is worth remembering where we have come from. The ordinary miracles we carry in our pockets. The stress we no longer feel. The friction we have forgotten existed. Progress is real, even if we only notice it when it fails.

The question is whether we can maintain that same thoughtfulness as we approach AGI. Can we deploy power responsibly when we have barely managed to deploy convenience without consequence? Can we regulate intelligence when we struggle to regulate persuasion?

I am not optimistic that we have time. But I remain convinced we must try. The alternative is to pretend we are prepared when we are manifestly not. That delusion will not protect us. It will only ensure that when the moment arrives, we are looking the wrong way.

2026 is the year we stop pretending. Either we act with urgency, or we discover what happens when transformative capability arrives in the absence of preparation. History does not wait for permission. Neither will AGI.

Until next Sunday,

David

David Richards MBE is a technology entrepreneur, educator, and commentator. The Sunday Signal offers weekly insights at the intersection of technology, society, and human potential.

© 2026 David Richards. All rights reserved.