The Sunday Signal: The Pitch, The Discipline, and The Deloitte Debacle

Essential insights on money, founders and accountability Issue #26 – Sunday 12 October 2025

The Bottom Line Up Front

Great pitches sell a problem, a product and a path to money. The best do it with ruthless clarity and proof. My column this week asks whether you can raise too much and still keep the day-one hunger. And in Australia, Deloitte has refunded the government after an AI-polluted report with fake references slipped into the public record. The lesson across all three stories is the same. Style without substance always gets found out.

How To Pitch Like It Matters

A pitch deck is not a scrapbook. It is a weapon. Used well, it cuts through noise, exposes the pain, shows a clean solution and names the prize. Used badly, it becomes an art project with a burn rate.

Dropbox. The classic Sequoia-era deck is spare and unforgiving. It names the everyday pain of file sync, shows the product and promises a demo rather than adjectives. Investors were buying inevitability. Dropbox closed a $6 million Series A in October 2008, led by Sequoia, which bought time to scale a product users already loved.

UberCab. Before the brand shortened to Uber, the deck framed the enemy. Medallions. Radio dispatch. Dead time. Then it offered the fix: one-click digital hail, cashless billing and the right to rate your trip. It read like a transport company with software, not a lifestyle brand. That clarity carried into the capital stack: a seed round of $200,000 in 2009, followed by a $1.25 million angel round in 2010, led by First Round Capital.

AirBed & Breakfast. The opening line is disarming in its plainness: book rooms with locals rather than hotels. Three screens show search, review and book. A scrappy adoption plan piggybacks on big events. It is not polished. It is focused. The result was a seed round of roughly $600,000 in 2009 from Sequoia Capital and Y Ventures, after a tiny Y Combinator cheque.

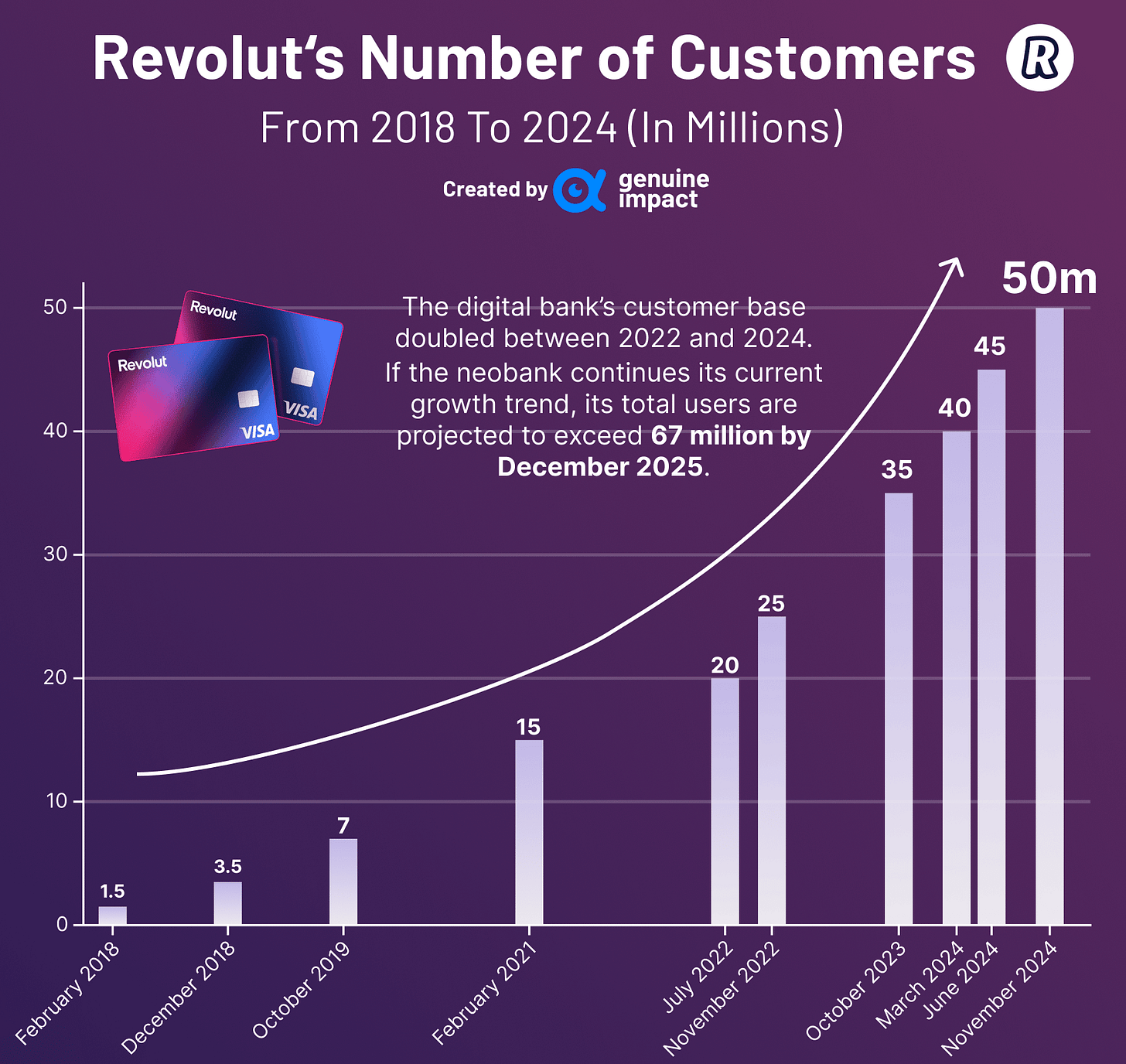

Revolut. The deck punches first: spending and sending money abroad is painful. Then it sells a machine, not a mood. Interbank rates, viral loops, crisp asks. Revolut raised £1.5 million in 2015, then $10 million in 2016, and later extended the seed to about $4.8 million as top-tier firms piled in.

Why these decks worked.

They do four things well.

First, they state the problem in a sentence humans recognise. Second, they show the product instead of describing it. Third, they point to distribution that already exists. Fourth, they respect time. Most bad decks sell adjectives and market size. The good ones sell inevitability.

Did The Decks Deliver?

Dropbox. The promise was brutal simplicity. It delivered. Dropbox turned a demo into a mainstream tool with more than 18 million paying users and $2.55 billion in 2024 revenue. Founder Drew Houston is now worth about $2.2 billion and remains CEO, though the company has cut staff to refocus on AI and productivity tools. It proved the pitch, but also the limits of a single-product platform in a world of free cloud storage.

Uber. The 2008 deck’s “one-click car” and “rate your trip” read like prophecy. Uber became a logistics empire across rides, freight and delivery, producing $44 billion in 2024 revenue and its first full-year profit. Co-founder Garrett Camp has a net worth of around $4.5 billion. Travis Kalanick, ousted after cultural scandals, left with roughly $2.7 billion, and now runs CloudKitchens. The slide that forecast $1 billion in best-case revenue undershot reality by fortyfold.

Airbnb. “Book rooms with locals rather than hotels” became an $11 billion revenue platform with $2.6 billion net income in 2024. The founders, Brian Chesky, Joe Gebbia and Nathan Blecharczyk, are each worth around $9–10 billion. Chesky remains CEO. The product outgrew its humble pitch into a cultural verb. The deck’s promise of cheaper travel and human connection turned into a company that rewrote the hospitality industry.

Revolut. What began as a pitch about foreign exchange fees became a global financial super-app. Revenues hit £1.8 billion in 2023, profits turned positive and customer numbers passed 38 million. Founders Nikolay Storonsky and Vlad Yatsenko are each now worth over £2 billion, as Revolut eyes an IPO that could value it near £30 billion. The early slides promised convenience. The company built a bank without branches.

Verdict. Three out of four overshot their own ambition. Uber and Airbnb outgrew their markets. Revolut redefined its category. Dropbox fulfilled its promise but matured early. Each validated its pitch in reality. None succeeded because of design flair. They succeeded because the product did exactly what the slides claimed it would.

Can You Raise Too Much Money?

My weekly column in the Yorkshire Post

The four decks share something money cannot buy: restraint. Dropbox, Uber, Airbnb and Revolut all raised enough to move but not enough to lose discipline. They used early capital to find proof, not prestige. They fought for customers before they fought for valuation. That fight created the muscle memory that later rounds could not destroy.

Dropbox’s founders lived in a shared apartment when they raised their Series A. Uber’s first cheques were small enough to keep focus on product-market fit, not politics. Airbnb’s founders sold novelty cereal boxes to keep the lights on before Sequoia came calling. Revolut’s first round barely covered launch costs, yet it delivered a global fintech within a decade.

Each began with necessity, not abundance. Scarcity built culture. Scarcity built edge.

Too many founders today forget that money is not the mission. They pitch investors rather than users. They build for the next round rather than the next customer. Capital becomes a trophy, not a tool. When that happens, the culture shifts from shipping to justifying. The energy that once fuelled ingenuity is diverted into burn management and board theatre.

It is possible to raise too little and starve. It is just as easy to raise too much and drown. The danger is not failure. The danger is comfort. When the runway stretches years into the future, the fear that keeps founders honest disappears. Urgency turns into opinion. Costs rise to match the cash available. Decisions take longer because they can. That is when mediocrity creeps in.

The strongest founders treat a big round as a temporary licence to accelerate, not an excuse to coast. They compress time. They hire deliberately. They remember that every pound raised is a promise to grow faster, not slower. When the wire lands, the job has only just begun.

Money has gravity. It pulls companies towards bureaucracy. It rewards presentation over production. The only way to resist that gravity is through discipline and hunger. The best founders find ways to keep the start-up edge alive long after the start-up stage has passed.

Dropbox stayed lean and profitable before listing. Airbnb cut deep during the pandemic and returned stronger. Uber pivoted to delivery and logistics when rides stalled. Revolut scaled without the infrastructure bloat that kills most banks. Each rediscovered scarcity even in times of plenty.

Abundance is the oldest trap in business. It flatters the ego, fattens the headcount and kills the urgency that makes companies great. The discipline that gets you funded is the discipline that keeps you alive. When the money arrives, the hunger must stay.

Capital is not victory. It is debt to the future. Every round buys time to earn the next one. The true test of leadership is whether that time is used to prove the market or to decorate the office.

Read the Full Column in the Yorkshire Post

Deloitte’s AI Hangover

Deloitte Australia has agreed to refund part of a A$440,000 fee after a government report turned out to be riddled with errors, including fake academic references and a fabricated legal quote. A corrected version now admits the use of a generative-AI tool based on Azure OpenAI GPT-4o, which had never been disclosed in the original. The Department of Employment and Workplace Relations says the recommendations are unchanged. Critics are not convinced, and they should not be. If the scaffold is rotten, the roof does not stand because you say it does.

In July, the report was published. Within days, Dr Christopher Rudge at the University of Sydney spotted fictitious citations and an invented quote from a Federal Court judgement. Deloitte ran an internal review and quietly posted a revised report before a long weekend. The new version reveals that AI had been used to fill “traceability and documentation gaps”. That phrase deserves translation. It means a machine-generated analysis that professionals failed to check.

This is not a side note. Deloitte sells AI training and ethics to clients while boasting of its own responsible use. Yet here it failed the first test of transparency. If a firm paid to audit others cannot audit its own work, what chance does anyone else have?

AI is not the villain. Complacency is. Tools do not hallucinate in isolation. People choose to trust them. The fix is simple. If AI touches research or analysis, the disclosure belongs on page one. Every citation must be checked by a human who signs their name. Every government contract should demand that proof. Until then, caveat emptor.

🚀 Final Thought

When The Money Arrives

The best decks do not woo. They corner you with truth until the only answer is yes. Dropbox showed it. Airbnb proved it. Uber and Revolut lived it.

Abundance, not scarcity, is the modern founder’s test. It dulls judgment and flatters mediocrity. The founders who win are those who stay paranoid even when the account is full. They treat money as borrowed time. They run as if the lights might go out.

Consulting giants, too, could learn from that hunger. Deloitte’s failure was not technological. It was cultural. When presentation becomes a substitute for proof, collapse is only a deadline away.

Money and machines share one weakness. They make people believe they no longer need discipline. But the world still rewards execution, not excuses. Investors buy inevitability. Customers buy outcomes. Governments buy accountability.

The lesson is eternal. When the money arrives, do not relax. Build faster. Hire sharper. Question harder. The next cheque is never guaranteed.

Until next Sunday,

David

David Richards MBE is a technology entrepreneur, educator, and commentator. The Sunday Signal offers weekly insights at the intersection of technology, society, and human potential.

© 2025 David Richards. All rights reserved.