The Sunday Signal: The Great Tech Battles

Essential insights on technology, power and human ambition Issue #30 – Friday 7 November 2025

The Bottom Line Up Front

Technology has always been a fight for control.

Every generation has its wars. Sinclair and Curry fought for the soul of British computing. Jobs and Gates battled for the desktop. Musk and Bezos now duel for space. The names change, but the motive does not. It is always about who owns the platform, who controls the data, and who defines the future.

This week’s Sunday Signal looks at the great battles that shaped and still shape technology, from the early rivalries that built Britain’s computer industry to the modern fights now reshaping search, AI and space.

The first article expands on my column in the Yorkshire Post, where I argue that the next browser war could mark the death of search as we know it. For twenty years, Google has been the front door of the internet. That door is now closing.

The second revisits the rivalry between Sir Clive Sinclair and Chris Curry. It began with genius, ended with a punch, and gave Britain one of its most brilliant moments of innovation.

The third explores the global conflicts that followed, from Apple against Microsoft to Google against everyone, and the new wars now unfolding between OpenAI, Microsoft and Google.

Technology is never polite. It advances through rivalry, pride and collision. Every great leap forward began with someone deciding that the world’s existing version was not good enough.

The Death of Search

The browser wars are back.

My column in this week’s Yorkshire Post looked at how a quiet revolution is unfolding that could end search as we know it. The last time this happened was the 1990s, when Microsoft bundled Internet Explorer into Windows and crushed Netscape. It took two decades and a new generation of entrepreneurs to break that monopoly.

Now the fight is not about browsers but about who owns answers.

For twenty years, search has been the internet’s front door. Google built its empire on the promise of choice. Type a query, receive a list. We assumed that was neutrality. It was not. Every link, every ranking, every sponsored result has been shaped by an algorithm tuned to its own incentives.

The arrival of AI chat interfaces changes that forever. When you ask ChatGPT, Copilot or Gemini a question, you no longer get ten blue links. You get one response. The entire architecture of the web, from advertising to publishing, depends on those links. Remove them, and trillions of dollars move overnight.

That is why Microsoft, Google and OpenAI are now locked in the fiercest corporate battle of the decade. Microsoft has staked its brand on Copilot, using OpenAI’s models to rewire Office, Windows and Bing. Google has rebuilt its core around Gemini, desperate to protect the cash machine that funds everything else. OpenAI, flush with billions and power, is quietly building its own browser, threatening to become both supplier and competitor to its largest investors.

The fight is not technical. It is existential. Whoever controls the interface controls the attention, and whoever controls the attention controls the money.

The irony is that the technology which made search better could also destroy it. AI-generated answers compress the web into summaries that no one clicks. Publishers lose readers. Advertisers lose metrics. The internet becomes a black box that tells you what it thinks you want to hear.

When Microsoft destroyed Netscape, the courts called it monopoly abuse. When Google displaced Internet Explorer, we called it innovation. What happens when the machine itself becomes the monopoly?

Search built the modern internet. AI may now bury it.

Battle at the Baron of Beef

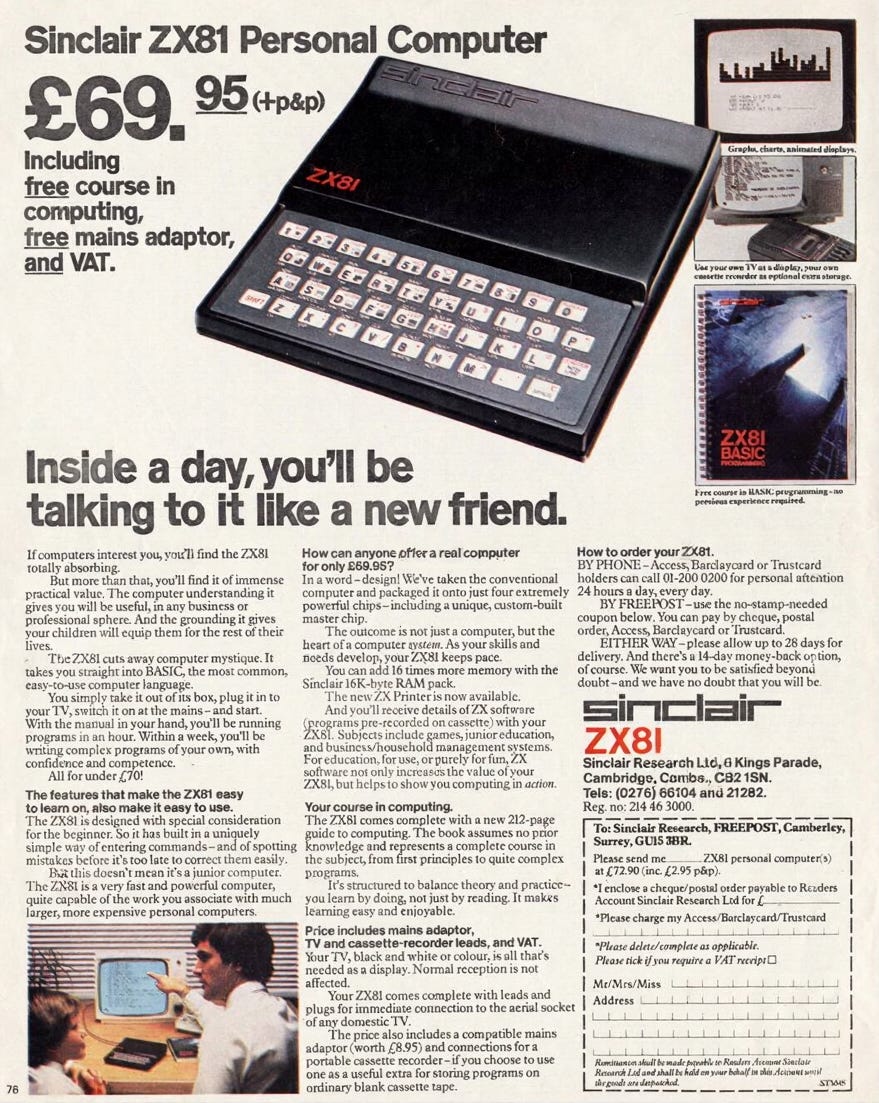

The first computer I ever touched was a Sinclair ZX81 at my middle school in 1981. I was eleven. Our headteacher, Mr Hall, proudly demonstrated his new skill:

10 PRINT “HELLO”

20 GOTO 10

The screen filled with endless greetings. We stared in awe.

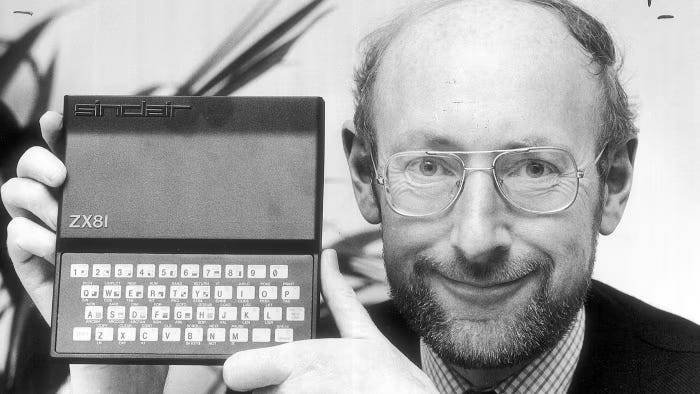

Sir Clive Sinclair brought technology to the masses. He believed computing should be cheap, accessible and British. His ZX80 and ZX81 sold for under £100 when anything comparable cost five times as much. For the first time, ordinary families could own a computer. My first machine was a ZX Spectrum. Out of necessity, I learned to code. I wanted to write games and, better still, to cheat at them. I remember changing a few lines of code so the football goal stretched across the entire screen, much to the frustration of my friends.

Sinclair’s genius was simplicity. He stripped away cost and complexity. His failure was timing. The world was not yet ready for his electric C5 vehicle. History now credits him as the man who foresaw the rise of the EV, decades too soon.

Across town, another Cambridge visionary was building his own empire. Chris Curry, a former colleague turned rival, co-founded Acorn Computers. I later owned one of their Electrons, the smaller cousin of the BBC Micro. It was rugged, brilliant and underappreciated.

In 1982, the BBC launched its computer literacy project. It taught an entire country to program over the summer holidays. Tens of thousands of children wrote their first lines of BASIC because of that programme. Acorn won the BBC contract and with it, national fame.

The two men could not have been more different. Sinclair, the ascetic perfectionist. Curry, the practical engineer. Both were visionaries. Both were stubborn. Their rivalry produced some of the most important innovations in modern computing. Acorn’s engineers went on to create ARM, whose chip architecture still powers nearly every smartphone on the planet.

Their competition, however, turned bitter. Advertising spats, product jibes and pride pushed them beyond words.

In December 1984, after their respective Christmas parties, they met in a Cambridge pub called the Baron of Beef. Words were exchanged. Sinclair hit Curry with a rolled-up newspaper. Curry retaliated with a punch. The scuffle spilled into a nearby wine bar to the astonishment of drinkers. Two of Britain’s greatest inventors brawling in public.

It was absurd and human and somehow fitting.

Sinclair and Curry had fought for the soul of British computing. Their feud symbolised the nation’s brief moment at the forefront of technology, when a few people in small rooms could change the world.

They later made peace. The fight became legend, immortalised in the BBC drama Micro Men. The rivalry drove them both to create machines that inspired a generation. My own journey into computing began with their war.

Today, the tech titans fight with code, lawyers and market share instead of newspapers and fists. The stage is global, the budgets astronomical, the egos unchanged.

The Great Tech Battles

Every generation thinks it invented competition.

In truth, the great battles of technology repeat themselves with new weapons. Each fight begins with vision, escalates into greed, and ends in consolidation.

Apple vs Microsoft. Jobs and Gates began as partners, ended as combatants. Their war was not about software but philosophy. Closed design against open licensing. Craft against scale. Gates won the desktop. Jobs won the decade.

Apple vs Samsung. A decade later, the smartphone war went nuclear. Apple accused Samsung of copying the iPhone’s design. Dozens of lawsuits across continents followed. Apple eventually won the money. Samsung won the market share.

Microsoft vs the U.S. Government. In the late 1990s, the Justice Department sued Microsoft for bundling Internet Explorer with Windows. The case reshaped antitrust law and set the stage for Google’s rise.

Google vs Apple. Android and iOS divided the planet. Jobs called Android a stolen product and promised thermonuclear war. He lost that battle but won something larger: loyalty.

Amazon vs the world. From Diapers.com to every high street retailer, Amazon perfected the art of predatory pricing. Its ambition was not victory but inevitability.

Meta vs the FTC. The social empire now faces the reckoning it delayed for a decade. Regulators want to unwind Instagram and WhatsApp. The question is whether monopoly law can keep up with the speed of the algorithm.

Epic vs Apple and Google. Fortnite’s maker challenged the 30 percent app store tax. The lawsuits exposed a cartel dressed as convenience.

SpaceX vs Blue Origin. The latest frontier. Musk and Bezos fighting not for customers but for orbits. The stakes are higher than market share. This is a battle for the narrative of the human future.

The names change. The pattern does not.

Each battle starts with vision. It ends with monopoly. Innovation begins in garages and ends in courtrooms. The creative act becomes the corporate moat. The dreamers become the defenders.

The next battles are already here. Microsoft, Google and OpenAI are redrawing the map of information. Tesla, Rivian and BYD are rewriting mobility. Anthropic, Meta and Elon’s xAI are vying for intelligence itself.

Technology has always been theatre for the human condition. Rivalry is how progress happens. But every war leaves wreckage. Netscape, Nokia, BlackBerry, MySpace, all once seemed untouchable. The next generation of giants will fall the same way.

In the end, all innovation is rebellion. The question is who you are rebelling against.

Final Thought

The battles of technology are never about machines. They are about people.

From the pubs of Cambridge to the boardrooms of Silicon Valley, the same forces drive every leap forward: ambition, pride, envy, and obsession. Every new device, every platform, every line of code carries the fingerprints of those emotions.

We like to believe progress is rational. It rarely is. The great breakthroughs are born from friction, from someone who refuses to accept the limits imposed by others. Every generation needs its rebels, but rebellion has a cost. For every Apple and Microsoft, there is a Sinclair, a Netscape or a Nokia that fades into history.

The current wave of AI giants believe they are building tools to serve humanity. In truth, they are fighting to own it. Each wants to be the interface through which the world sees itself. The next decade will decide who wins that power, and whether we ever take it back.

The British computer pioneers of the 1980s fought with code, paper and pride. Today’s titans fight with data, regulation and algorithms, but the emotion is the same. The line between creation and domination is thinner than ever.

Technology always promises liberation. It rarely delivers it for long. The web freed information, then fenced it in. AI will do the same unless we insist on openness, transparency and accountability.

The future will not be decided by who has the best technology, but by who uses it with the greatest moral imagination. The test of progress is not how fast we move, but who gets to move with us.

The battles ahead will define not just industries, but values. The companies that forget that will win the quarter and lose the century.

Read The Sunday Signal first every Friday on Substack.

Public release follows on Sunday.

Still think tech rivalry is new?

In 1984, Sir Clive Sinclair hit Chris Curry with a rolled-up newspaper in a Cambridge pub.

Today’s founders would have live-streamed it, monetised the replay and called it a brand collaboration.

Progress.