The Sunday Signal: The Education Illusion

Essential insights on education, economics and power Issue #29 – Friday 31 October 2025

The Bottom Line Up Front

This week is about the myths we still tell ourselves about education and success.

Universities say they exist to cultivate talent, yet their balance sheets look more like hedge funds than classrooms. Britain’s degree model still assumes that three years of lectures are the only route to skilled work, even as employers and technology move on. And the world’s most successful founders, artists and innovators quietly prove that formal education is no longer the defining filter for brilliance.

Three pieces this week. First, how elite universities became asset managers with lecture halls attached. Second, why Britain’s university business model is breaking under pressure. And third, five people who never went to university yet mastered fields where degrees were supposed to be mandatory.

If power follows money, success still follows curiosity.

The 56.9 Billion Dollar Classroom

Harvard University’s endowment now stands at $56.9 billion, the largest academic fund in the world. The number is so vast that it changes what Harvard is. It is not a university that happens to have an endowment. It is an endowment that happens to run a university. Harvard’s own fiscal 2025 report confirms the figure and notes that endowment distributions now account for nearly forty per cent of operating revenue.

To grasp the scale, look at the next few in line. Yale holds $44.1 billion, Stanford $40.8 billion, Princeton $36.4 billion and MIT $27.4 billion. Across the Atlantic, Oxford’s combined university and college endowments total £8.7 billion, Cambridge’s £7.1 billion, with Edinburgh at £580 million, King’s College London at £325 million and Glasgow at £262 million. Harvard could buy the top five British universities outright and still have change left over.

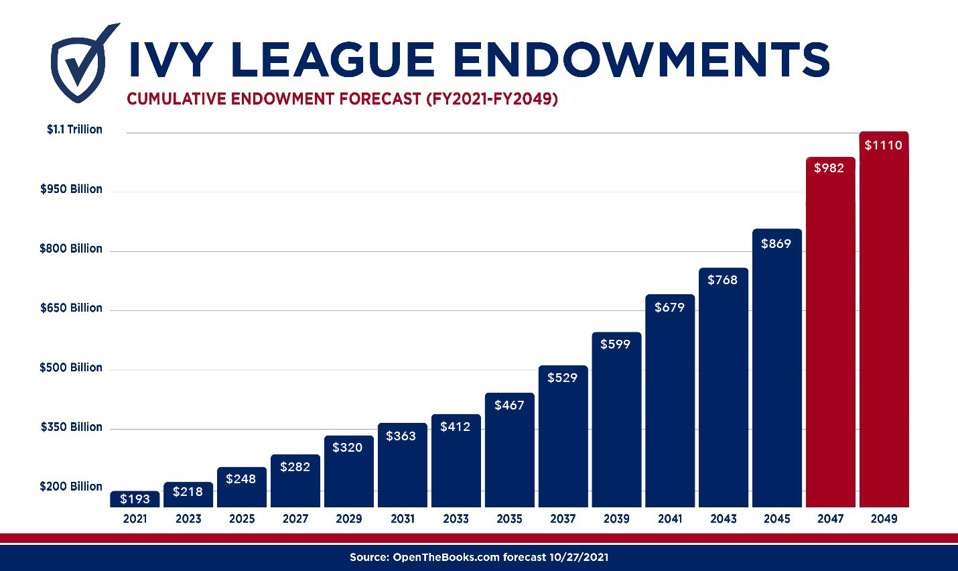

Now add the Ivy League lens. In a single year, the Ivies added roughly $48.4 to $48.6 billion, taking their collective endowment to about $192.6 billion, up from $144 billion in 2020. A watchdog analysis argues that, on current patterns, the Ivy total could pass $1 trillion around 2048, with assumptions that mirror historic returns and standard five per cent spending rules. The same analysis lists the then-current campus figures as Harvard $53.2 billion, Yale $42.3 billion, Princeton $37.7 billion, Penn $20.5 billion, Columbia $13.5 billion, Cornell $10 billion, Dartmouth $8.5 billion and Brown $6.9 billion, and notes that Harvard’s endowment already exceeded $10 million per undergraduate at that point. Treat the trillion as a forecast, not a certainty, but the direction of travel is unmistakable.

Organised as charitable nonprofits, these institutions pay little or no taxes on investment income, capital gains and campus property, which is why critics ask whether the Ivy model is gaming federal, state and local tax systems while still charging sticker prices near $80,000 for tuition, room and board. The tension between tax privilege, rising prices, and compounding capital is the heart of the optics problem.

This is not an education market. It is a capital market. Harvard Management Company employs more finance professionals than many FTSE firms. Yale’s investment office is run like a private equity house. Stanford’s annual investment returns exceed the GDP of small nations. When universities hold that much capital, money becomes culture. The portfolio pays for the mission, but it also sets the limits of what that mission can be. A one per cent move in a fifty billion dollar fund equals half a billion dollars. A university president can talk about access and inclusion. The investment committee decides what is possible.

That power shift would matter less if education itself were still scarce. For centuries, the university’s moat was knowledge. The brightest minds wrote books. The library was the differentiator. To be educated, you had to live near the shelves and, ideally, near the people who filled them. Then the moat vanished. When knowledge moved online, the scarcity disappeared. What Netflix did to Blockbuster, the internet did to the library. Netflix did not win by building bigger stores. It changed the channel of delivery. Suddenly, you did not need to live next to a library to access the best ideas ever written. Information became ubiquitous. The marginal cost of enlightenment fell to zero.

If information is free, then in theory, where you go should not matter. Yet the brand matters more than ever because universities discovered a new scarcity to sell. Status. Parents crave proof that their DNA works. “My daughter goes to Harvard.” “My son got into Stanford.” “She is at Oxford.” These sentences light up dinner tables because they are emotional currency. The product is no longer knowledge, which is a commodity, but validation, which is priceless.

Harvard is an investment trust with a student body. Stanford is a hedge fund with an education programme. Oxford is an endowment with spires. They compete not on content, which is free, but on context. The tutorials, the networks, the internships, the nameplate. These are the scarce things that capital buys and that parents will pay for, whether directly or through donations, debt or legacy gifts.

The paradox is brutal. The internet made knowledge abundant and access cheap, yet elite universities have never been more expensive or more powerful. They thrive because they are not selling knowledge at all. They are selling narrative. And as long as the story still makes parents feel proud and employers feel safe, the hedge funds with classrooms will keep compounding both influence and returns.

Knowledge is now a commodity. Vanity is not.

Britain’s Broken University Model

Based on my weekly column in The Yorkshire Post

Five years ago, around our kitchen table, five of my daughter’s close friends told me why they went to university. Each one said the same thing. To get a good job in the field they were studying. Chemistry. Biology. Business. Today, not one of them works in that field. The promise looks shaky.

Tony Blair’s target to send half of young people into higher education turned a path into a pipeline. The target was met and then treated as a success in itself. The world of work moved faster than the model that feeds it.

We also lost something in the rebrand. Polytechnics were created to keep learning close to industry. They taught applied skills and produced job-ready graduates. But class snobbery pushed them to rename themselves as universities in the 1990s because practical was seen as lower than academic. Britain paid for that conceit. In the United States, polytechnic universities such as Cal Poly never lost prestige because employers value what people can do on day one.

The signals now are worrying. Researchers parsing hundreds of millions of job ads across nearly three hundred thousand firms have found that since early 2023, junior hiring at companies adopting generative AI has fallen almost eight percent relative to non-adopters. Senior hiring barely moved. The squeeze lands hardest on graduates from mid-ranked universities. Vocational routes and the very top tier hold up better.

Treat that as a forecast for Britain.

Against that backdrop, do degrees deliver on the test that matters most, a good job in the area studied? The record is mixed. Many graduates land high-skilled roles, but roughly a third do not. A large share never work in a field related to their subject. The graduate premium survives on average but is uneven by course and institution. If a student borrows heavily and never sees the promised outcome, that is a broken deal.

And it is about to get tougher. AI is stripping out the routine tasks that justified entry-level jobs in consulting, law, finance and software. With fewer stepping stones, employers raise the bar for first jobs and pay up for experience. Practical skills and elite brands hold value. Mid-tier generalist routes get squeezed.

Financially, the model is fragile. International fee income has kept the show on the road. But policy shifts on visas and weaker global demand are biting. One-year master’s programmes feel it first. A system that relies on ever more overseas students is a gamble with political risk.

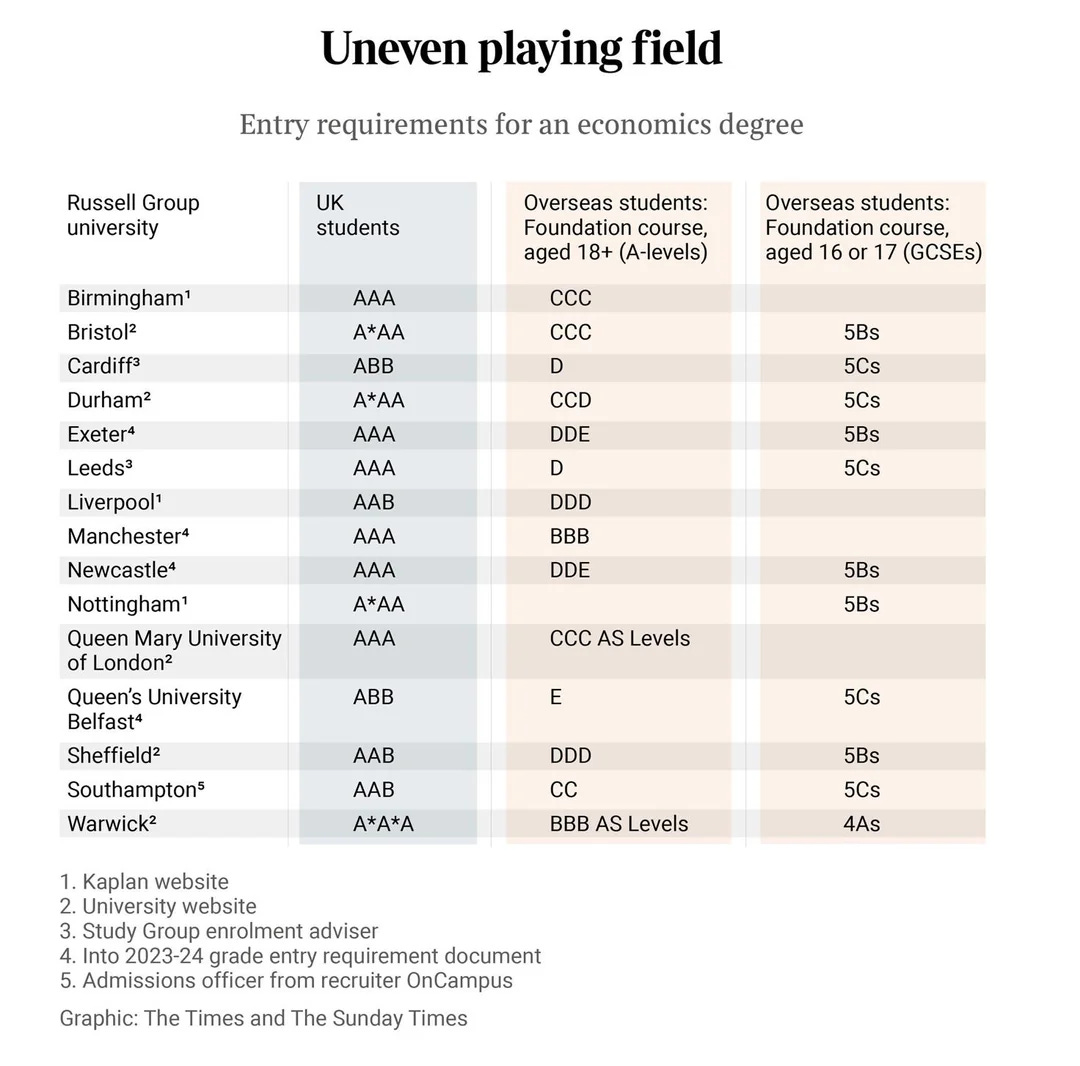

The numbers tell the story more clearly than any speech can. Russell Group universities demand top A-level grades from British students, often A or A*, while admitting overseas students to the same courses with far lower requirements. For economics, Birmingham asks AAA from UK students but CCC from international ones. Leeds requires AAA at home and a single D abroad. At Sheffield and Liverpool, some overseas entrants are accepted with DDD or even E grades. This is not a gap in ability. It is a gap created by economics. Home fees are capped. International fees are not. The pressure to plug funding holes has turned equality of entry into a luxury the system no longer affords. When grades are adjusted to match cashflow, education stops being a level field. It becomes a marketplace.

The fix begins with transparency. Every course at every university should publish its real outcomes, salaries, promotions and how many graduates land high-skilled roles in their field. If a course cannot show results, it should be fixed or closed. Students deserve to be buyers armed with data, not passengers on a marketing brochure.

The next step is partnership. Universities must co-design curricula with employers and hire in cohorts at the end. Build more degree apprenticeships that put people into real teams from day one. Create short, intensive bootcamps for fast-changing skills and refresh them annually. Focus on judgment, creativity and problem-solving, the things machines find hardest to automate.

And speed up. The economy now moves faster than the curriculum review cycle. Three-year degrees built on five-year update loops cannot keep up with markets that shift in months. Universities must do something they have never done before, get ahead of the curve.

Back to that kitchen table. Those first years did their part. Five years later, not one is in the field they trained for. If university is about gaining the skills for good work, it needs to deliver that outcome in practice, at speed and at scale. If it cannot, the model is broken. The smart institutions will move first. The rest will wait for the market to make the decision for them.

Five People Who Proved the Degree Myth Wrong

If degrees were the only path to success, these five people should never have made it. Each built a career in a field that supposedly requires a formal qualification. Each rewrote the rules by mastering what mattered faster and better than the system could teach it.

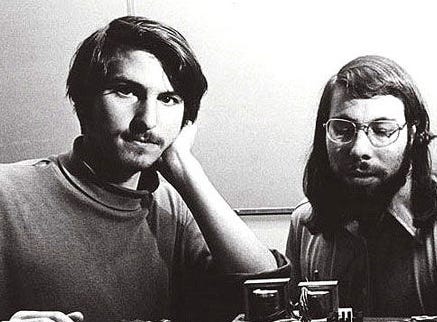

Steve Jobs left Reed College after six months. He audited classes he liked, slept on friends’ floors and wandered through calligraphy lectures for inspiration. That curiosity led directly to the first Macintosh, whose fonts and design language changed personal computing. He later said dropping out let him stop taking classes that didn’t interest him and start taking the ones that did. The discipline came from curiosity, not compliance.

Richard Branson never finished school, let alone university. He struggled with dyslexia and left at sixteen to start a student magazine. That side project became Virgin Records, then an airline, then a global group. Branson built a billion-dollar business portfolio without ever learning the theory of management. What he lacked in certificates, he replaced with instinct and an ability to sell an idea before he could afford to build it.

Oprah Winfrey attended Tennessee State University but left before graduating to take a job in local television. By twenty-four she was anchoring the news in Baltimore. By thirty-two she had created The Oprah Winfrey Show and changed daytime media forever. Her life proves that lived experience, empathy and relentless self-awareness can outshine any degree.

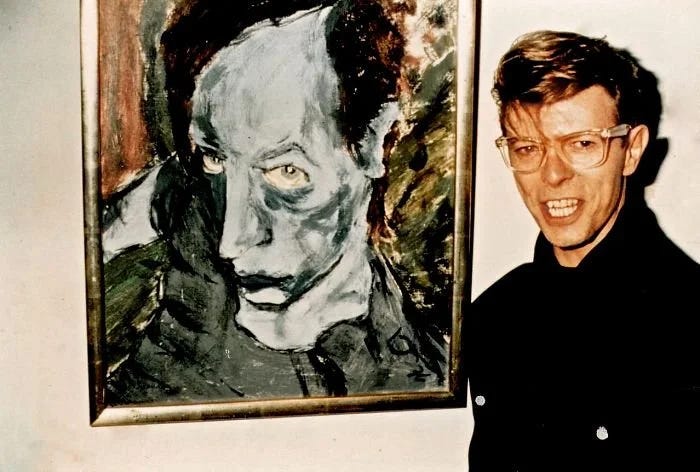

David Bowie trained not in music but in art and design, and never attended a conservatoire. Yet his understanding of visual storytelling, combined with self-taught musicianship, produced some of the most influential albums of the twentieth century. Bowie’s career demonstrates that mastery is a function of curiosity, not credentials.

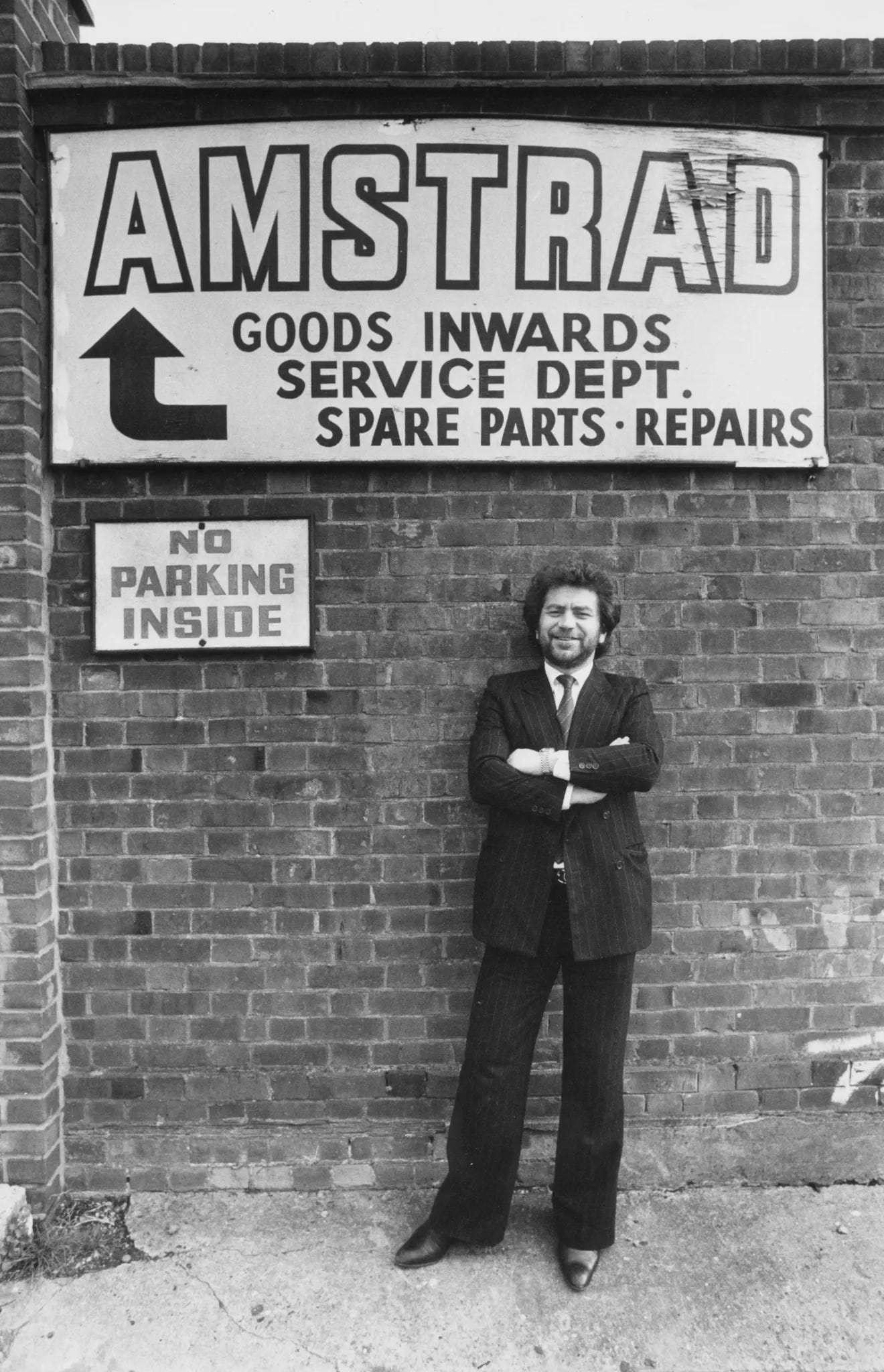

Alan Sugar left school at sixteen and began selling car aerials out of a van. That small business became Amstrad, a pioneer of affordable personal computers and consumer electronics. He later built a property and media empire and was knighted for services to business. Sugar went from the council estate to the boardroom in an industry dominated by engineers with degrees, proving that grit and commercial instinct can outrun any qualification.

These are not just anomalies. They are signals. In a world where knowledge is free and experience can be gained by doing, the credential is losing its monopoly on opportunity. Degrees still matter for professions where regulation demands them, such as medicine, law, and engineering, but even there, the walls are thinning. Apprenticeships, online credentials and AI-powered learning tools are beginning to break open the monopoly.

The lesson from these five is not that university is worthless, but that it is optional. What matters most is agency, the ability to learn without waiting for permission. The people who win now are those who act like founders of their own education.

If Harvard, Oxford and Cambridge are the temples of formal learning, Jobs, Branson, Winfrey, Bowie, and Sugar are proof that you can build your own altar. In the networked age, the qualification that counts is curiosity.

Final Thought

The library moat is gone. The British degree pipeline is fraying. And five people who ignored the map entirely still reached the summit. Across every sector, the pattern repeats: the world no longer rewards credentials. It rewards competence.

Universities used to be the gatekeepers of knowledge. They owned the shelves, the presses, the professors and the power. To be educated you had to pass through their gates. Now the gates are open, yet many of the gatekeepers still behave as if the walls are intact. They talk about widening participation while raising prices. They celebrate access while hoarding advantage. They sell the illusion of scarcity while sitting on billions.

The truth is that the world has outgrown the old hierarchy. Knowledge has escaped its keepers. A teenager in Lagos can learn AI faster than a postgraduate in London. A factory technician in Leeds can take the same coding courses as a Stanford student. The real divide is not between the educated and the uneducated. It is between the curious and the indifferent.

And that should terrify the institutions that built their power on control. Because once knowledge is free, their only defence is credibility. They cannot hide behind branding when results are public and outcomes are measurable. The next generation will not be impressed by marble halls and Latin mottos. They will ask a simpler question: does this place change my life?

That is the new contract. Universities that treat education as an investment product will be disrupted by those that treat it as a partnership. Those who hide behind tradition will be replaced by those who publish results. Those who cling to the prestige economy will lose to the curiosity economy.

The same rule now applies everywhere. The value of any institution: university, business, media, government will be measured not by its history, but by its honesty.

If Harvard is an investment trust with a lecture hall and Oxford is an endowment with spires, then the rest of us have a choice. Keep pretending the system still works, or build something better.

We are entering a decade where self-taught engineers will outpace certified ones, where apprenticeships will outrun master’s degrees, and where curiosity will be the new currency of mobility. The people who thrive will not be those who memorised the syllabus, but those who rewrote it.

Education once meant learning what others had discovered. Now it means discovering what others have missed.

The gatekeepers are out of excuses.

Read The Sunday Signal first every Friday on Substack.

Public release follows on Sunday.