The Sunday Signal: The Divide That Won’t Die, The Opportunity Fix, and The Uber Paradox

Essential insights on inequality, investment and automation - Issue #27 – Sunday 19 October 2025

The Bottom Line Up Front

Britain’s divide is not folklore. It is a fact. When I took my first job in London in the early 1990s, a senior executive flicked a fifty pence coin across the table and said, “There you go Richards, buy yourself a house in the North.” It was meant as humour, but like most humour, it carried truth. The divide between the City’s swagger and the North’s struggle was already fixed in the national imagination.

Three decades later, the gap remains. Power and capital stay in the South, while too many towns in the North, Midlands and coastal England fight slow decline. My work with the Social Mobility Commission has shown me that this is not geography. It is design.

The same story is playing out inside work itself. New research shows how artificial intelligence is already hollowing out the first rung of the career ladder. Even Uber now pays its drivers to tag data that will one day automate them out of a job.

The lesson is simple. A country that stops building ladders for its people eventually finds no one left to climb.

The Divide That Won’t Die

The North–South divide is Britain’s oldest open wound. It survived Thatcher’s revolutions, Blair’s optimism and every government promise of levelling up.

When I joined Druid Systems in the early 1990s, London was roaring. The Big Bang had turned the City into Europe’s financial capital. The suits were loud, the lunches long, and the bonuses obscene. Sheffield, where I grew up, was still counting the cost of pit closures and steel redundancies. The cultural shorthand was perfect. The South had Loadsamoney. The North had Yosser Hughes, a man begging for a job.

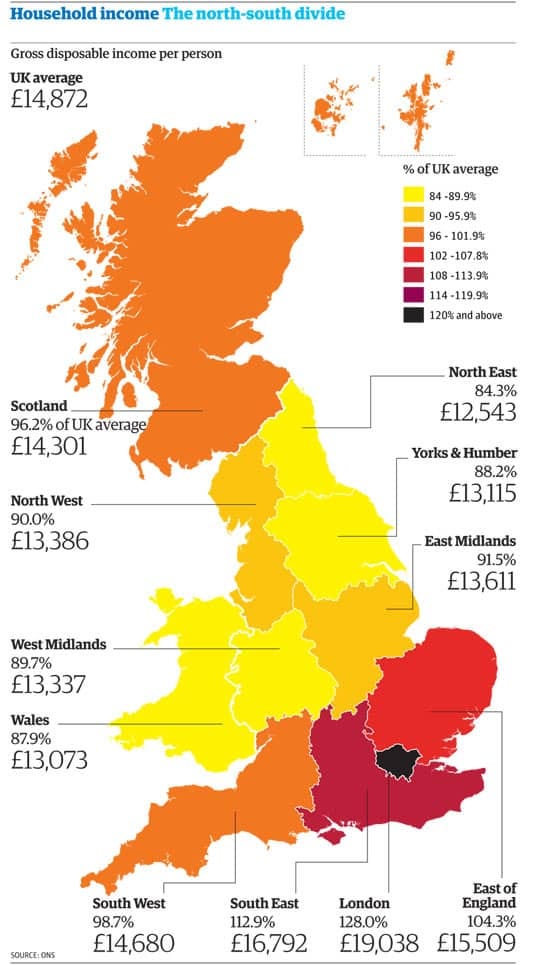

The numbers told the same story. By 1995, productivity in London was around forty per cent higher than in Yorkshire and the Humber. Weekly pay in the capital averaged £340 while the North East managed barely £250. Infrastructure spending per head in London was twice as high. Investment chased investment and the gap widened.

Every government tried to bridge it. John Major spoke of a classless society. Tony Blair promised education, education, education. For a while it worked. University access widened. Service industries grew. But the heart of the old industrial North was never replaced. By 2010 London produced a fifth of all UK output while large parts of the North were still living with the hangover of the 1980s.

Today Greater Manchester’s productivity is still thirty-five per cent below London. A child born in East Yorkshire has less than half the chance of climbing the income ladder than one born in outer West London. The pattern has not changed in a generation.

And yet the picture is not as simple as a North–South map. Deprivation is spread across the South too. Hastings, Clacton, Great Yarmouth, Torbay and Cornwall all rank among the poorest areas in Britain. This is not a compass problem. It is a system problem.

The real divide is between places with power and places without it. Between those who shape the economy and those who serve it.

The answer will not come from subsidies or slogans. It will come from self-sufficiency. Regions must be able to generate their own wealth, attract their own investment and keep their own talent. That means long-term local control of capital, skills and planning.

Every time a young person leaves Doncaster or Hull to make it in London, their hometown loses not just a worker but a role model. The geography of opportunity shapes the geography of belief. A nation cannot unite if half of it is told, quietly, that success means leaving home.

Fixing the Opportunity Gap

In the first year of the pandemic I took a phone call that changed me. Nancy Fielder, then editor of The Sheffield Star, told me thousands of children in South Yorkshire could not join online classes because they did not own a laptop. Whole classrooms were excluded from education because of a missing device.

It was not a technology problem. It was a window into a deeper truth. Britain’s opportunity gap is not about ability. It is about access.

That truth became the foundation of my work with Rob Wilson and the Social Mobility Commission. This month we published Innovation, Investment and Inclusion: A Framework for Regional Renewal. It is a practical plan built on a radical idea. Enterprise and innovation are not luxuries. They are the engines of social mobility.

Growth is not about GDP. It is about whether a child in Barnsley has the same chance to rise as a child in Brighton.

The report calls for three structural shifts.

First, create Opportunity Zones. These would offer powerful tax incentives for investors to back businesses in left-behind areas. Capital gains could be deferred or reduced if the money is reinvested locally through professionally managed funds with clear regional mandates. In the United States, Opportunity Zones have attracted more than one hundred billion dollars of private investment into disadvantaged communities. Britain can do the same, but only if the money funds enterprise and skills rather than speculative property deals.

Second, keep pension capital in Britain. Only 4.4 per cent of UK pension fund assets are invested in British equities, down from more than half a generation ago. The savings of British workers are being used to finance foreign growth while our own companies fight for survival. The Commission recommends that at least five per cent of every pension portfolio be ring-fenced for productive UK investments such as infrastructure, clean energy and regional funds. The capital exists. What is missing is will.

Third, devolve power with accountability. Every region should have a business-led Strategic Growth Plan backed by long-term national support. Devolution must mean authority, not abandonment. Whitehall should set outcomes, not rules, and then step back.

When I returned to Sheffield after two decades in Silicon Valley, I saw a paradox. Talent everywhere. Capital nowhere. That is why we built Yorkshire AI Labs: to show that world-class innovation can thrive outside the M25. But no single venture can fix a national habit. Britain still treats the North as an outpost of the South.

If we want to move from subsidy to self-sufficiency, we must unleash private capital alongside public purpose. Devolution without enterprise is bureaucracy. Enterprise without devolution is chaos. Together, they are the only route to a country that rewards talent wherever it is found.

Humans in the Loop

While Britain wrestles with geography, another divide is opening inside work itself.

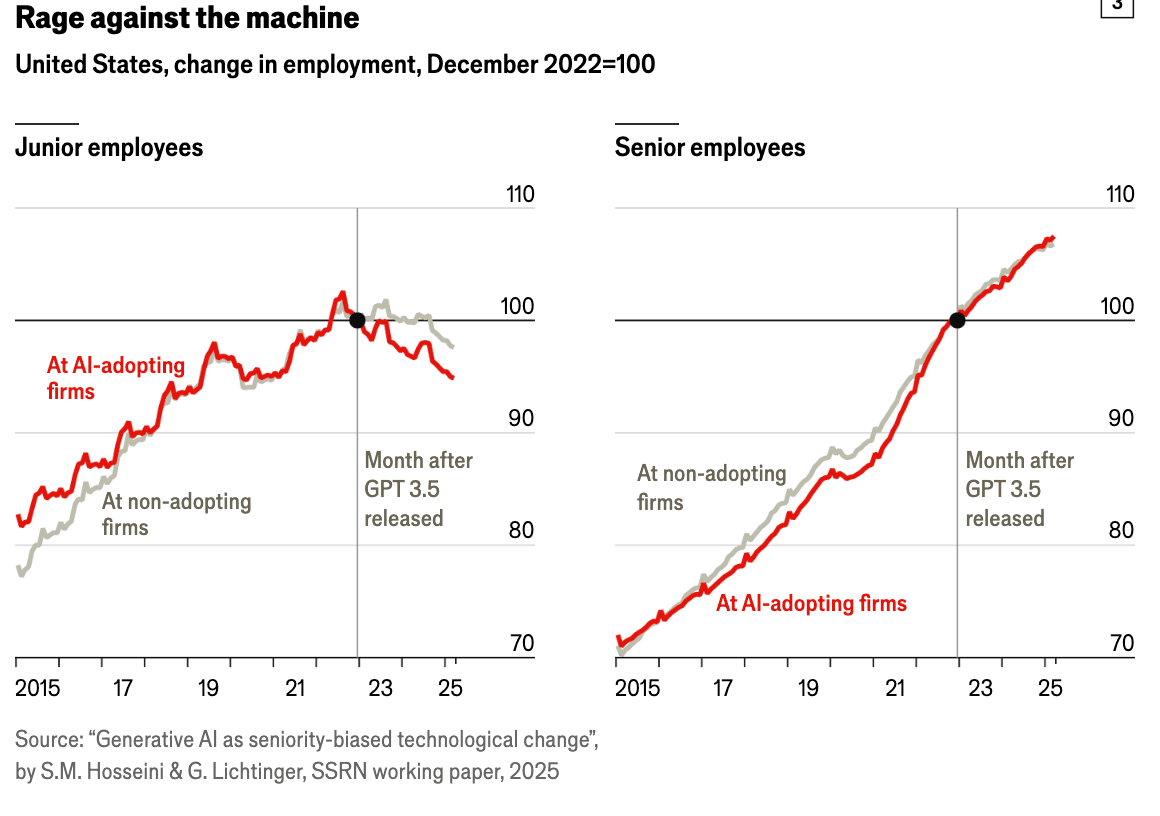

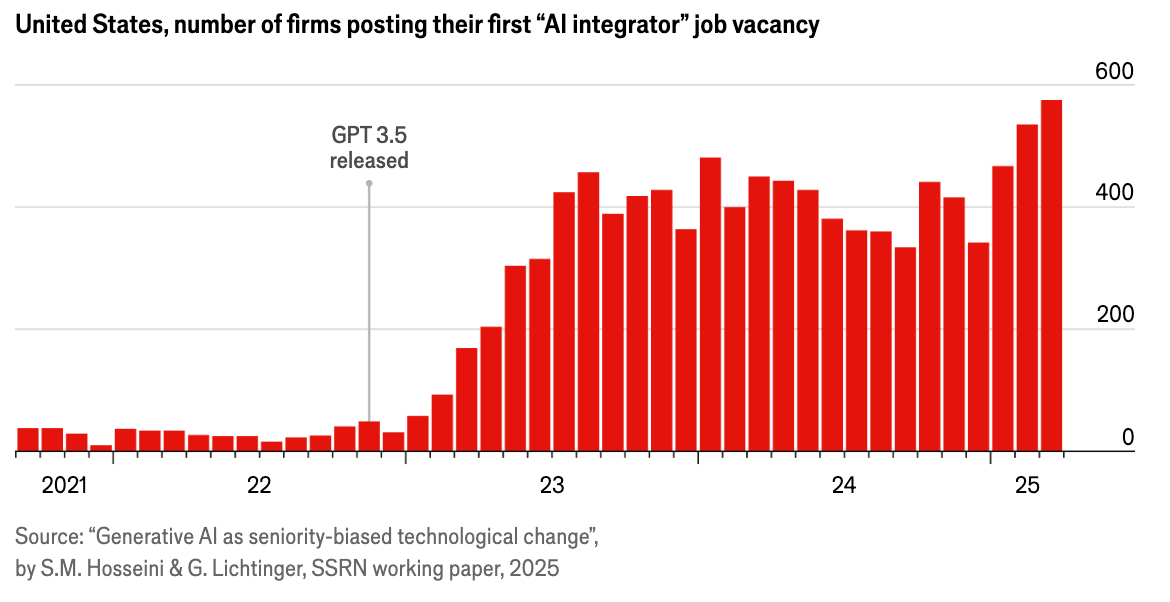

A new study from Harvard and Yale followed more than three hundred thousand companies. It found that firms hiring “generative AI integrators” to embed artificial intelligence into daily operations saw junior hiring fall 7.7 per cent faster than firms that did not. Senior hiring stayed level.

The implication is stark. AI is eating the entry-level job.

These are the roles that once taught people how to think. Junior coders, analysts, paralegals and assistants. The jobs that built discipline, judgment and professional instinct. Machines now do the grinding work once entrusted to people starting out. The ladder is being sawn off at the bottom.

The same logic is now reaching the gig economy. Uber has begun offering “digital tasks” to its American drivers. Drivers can earn small sums by uploading menus, recording audio clips or tagging data that trains machine-learning models. It sounds like diversification. It is really digital piecework. The drivers are training the systems that may one day replace them.

This is the new invisible labour of the AI age. Small, fragmented, and atomised. It echoes the nineteenth-century cottage industries where workers stitched garments at home for pennies a piece. The product has changed. The power dynamic has not.

Economists argue about the impact. Some see opportunity for flexible, remote income. Others see a new underclass of human cogs inside machine systems. What is certain is that automation is moving faster than adaptation.

The Harvard and Yale data show that graduates from mid-tier universities are most at risk. Elite graduates are retained for specialist skills. Lower-tier workers survive through lower cost. The middle is disappearing. The same hollowing that split the country is now splitting the workforce.

This is not a question of machines replacing people. It is a question of how we teach people to work alongside machines. Every generation learned by doing the work that technology now performs. If the machine learns faster than the apprentice, who trains the next expert?

The danger is not mass unemployment but mass deskilling. A society that automates its apprenticeships will soon find it has experts with no successors.

Final Thought: The Geography of Ambition

The North–South divide is physical. The divide between human and machine is psychological. Both are the product of concentration. When too much power sits in one city, the rest of the country becomes dependent. When too much intelligence sits in one algorithm, the rest of the workforce becomes dispensable.

The answer is to spread both. Spread opportunity. Spread learning. Spread agency.

We cannot code empathy into an algorithm or legislate pride into a region. But we can design systems that keep people inside the loop rather than outside it.

Whether it is a child without a laptop, a founder without capital or a driver tagging data for a machine, the story is the same. When opportunity is removed from people, progress stops.

Until next Sunday,

David

David Richards MBE is a technology entrepreneur, educator and commentator. The Sunday Signal offers weekly insights at the intersection of technology, society and human potential.

© 2025 David Richards. All rights reserved.

Hey, great read as always. The 'design' aspect of these divides, AI included, is so critcal.