The Sunday Signal: Never Give Away the Keys

Issue #41 · Sunday, 15 February 2026 On founders, boards, and the seven hundred billion dollar bet on who builds what comes next

The Bottom Line Up Front

Boards love the word “professionalise.”

It sounds responsible. Mature. Sensible.

In practice, it often means removing the person who made the company worth owning in the first place.

This week’s Yorkshire Post column was not theory. It was memory. I was fired in a hotel in Belgravia, with a document slid across a table, by a chairman I had appointed. Then I was reinstated days later.

The point is not that founders are infallible.

The point is that founders are not interchangeable.

History shows what happens when boards forget that. Sometimes they destroy billions in value. Occasionally they save the business.

At the same time, the largest companies on earth are making infrastructure bets so vast they are beginning to bend markets and power grids around them. Not hundreds of billions. We are now looking at combined capital expenditure approaching seven hundred billion dollars in a single year.

Two decisions.

Who leads.

And who builds.

Both define the next decade.

Raise Money. But Never Give Away the Keys.

Every ambitious founder should raise capital.

Whether that means venture capital, public markets or both, external money is how small companies become important ones. Capital gives you speed. Speed gives you market position. Market position gives you options.

The mistake is not raising money.

The mistake is giving away control before you have proven what you are building.

The pattern is painfully consistent. A founder with a strong idea and early traction takes a pre-seed or seed round. The term sheet looks generous. The valuation feels fair. But buried in the details are board seats, veto rights, anti-dilution clauses and preferred liquidation terms that shift power long before the company has found its footing.

By the time the founder realises what they signed, the investor is not a partner.

They are the landlord.

This is the difference between venture capital and private equity. Venture capital, in its best form, backs founders and accepts the wild variance that comes with early-stage conviction. Private equity buys control, installs management, optimises operations and extracts returns on a defined timeline.

Both models work. But they serve different purposes at different stages.

What is happening increasingly, and I see it locally, is venture investors behaving like private equity at the earliest possible stage. Taking board control at pre-seed. Installing their own chair before the product has reached market. Firing founders in the first innings of the game, not because the company is failing, but because the founder is not docile enough for the investor’s operating model.

This is not governance. It is capture.

When I was asked to sign that document in a hotel in Belgravia, I was a CEO who had built a company, taken it public and created hundreds of millions in value. And still the board I had constructed moved to remove me. I was reinstated days later. But the lesson stayed.

If it can happen to a founder at that stage, it can happen to anyone. And it is happening now to founders who have barely started.

A VC who removes a founder at seed stage is not protecting an investment. They are destroying the only thing that makes the investment worth making. At that point, the founder is not one part of the machine. They are the machine. The vision, the conviction, the customer relationships, the product instinct, the pace. Remove them and you are left with a cap table, a pitch deck and a set of Notion documents.

The lesson is not to avoid raising capital.

The lesson is to raise it wisely.

Understand what you are signing. Every term sheet is a transfer of power disguised as a transfer of money. Board composition, voting thresholds, reserved matters, drag-along rights. These are not admin. They are architecture. Get a lawyer who works for you, not one recommended by the investor.

Retain board control for as long as you can. At pre-seed and seed, there is no reason for a founder to surrender a board seat. If an investor demands one as a condition of a modest cheque, they are telling you exactly how they intend to behave when things get difficult.

Choose investors who have backed founders through adversity, not just through growth. Ask the question directly. Have you ever fired a founder? How early? Why? The answers will tell you everything.

Look at dual-class structures early. They are not just for IPOs. Zuckerberg controls Meta with roughly thirteen percent economic ownership because he holds the majority of voting shares. That structure was established long before the company went public. Founders who wait until listing to think about control have already left it too late.

Raise money. List when the time is right. Both are signs of ambition and confidence.

But never confuse a cheque for alignment.

And never assume that the person sitting across the table at your board meeting is building the same company you are.

When Firing the Founder Destroys Value

And When It Saves It

There is a pattern in corporate history. Boards replace visionary founders with operational leaders in pursuit of calm.

Calm is usually expensive.

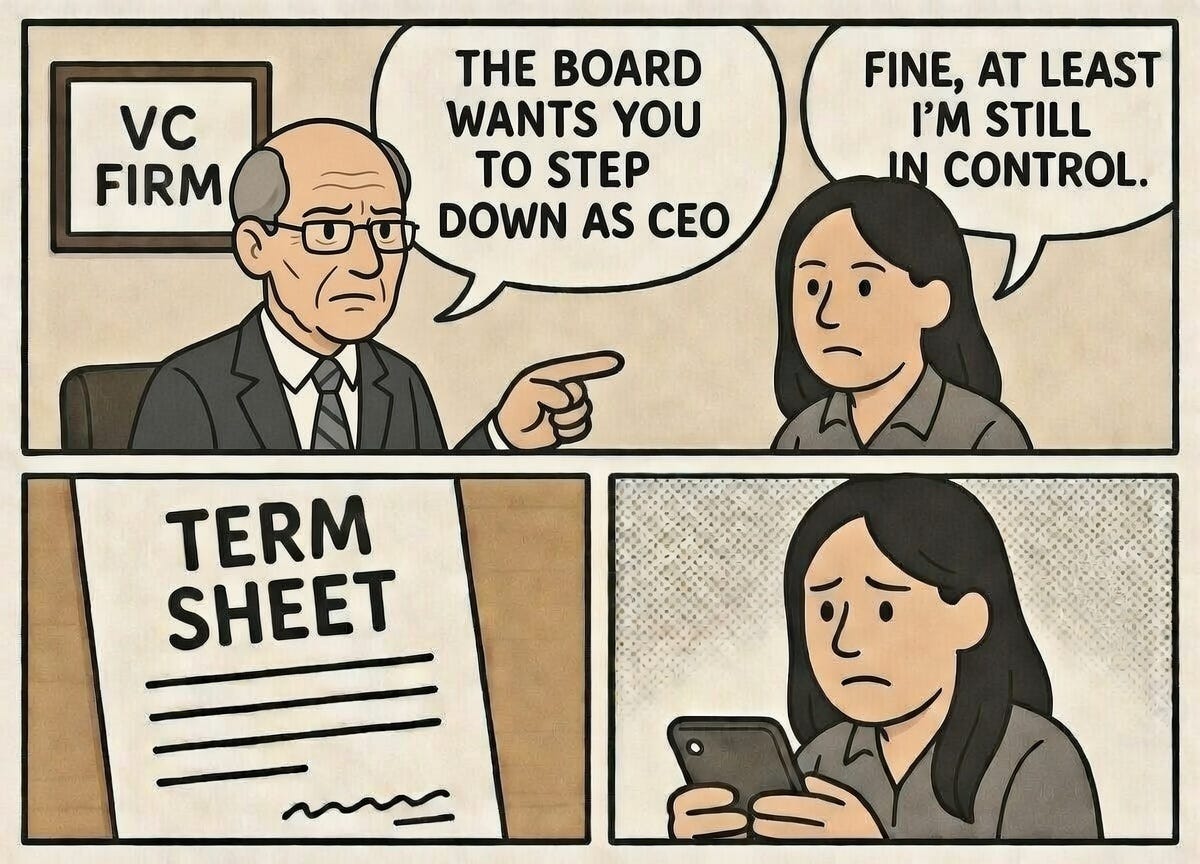

Consider Apple after the departure of Steve Jobs in 1985.

Apple did not implode. It diffused.

The Newton absorbed huge resources and became a cultural punchline for its flawed handwriting recognition. The Pippin was a forgettable attempt at gaming hardware. The Macintosh TV felt like a product without a thesis. The desktop line multiplied into Quadras, Performas and Power Macintoshes with marginal differences and mounting confusion.

There was activity everywhere. But no clarity.

By 1997 Apple was widely described as being within ninety days of running out of cash. Market share had collapsed from around sixteen percent to less than four. Annual losses hit $1.03 billion. The company that invented the personal computer revolution was being written off.

The board acquired NeXT, effectively to bring Jobs back. He eliminated around seventy percent of the product line. He cut the bewildering range of desktops to one. He cut portables to one. He negotiated a $150 million investment from Microsoft, of all companies, to keep the lights on. Ruthless focus returned. So did profitability.

The difference was not engineering talent.

It was taste.

Taste is the ability to say no. Taste is strategic subtraction. Taste is conviction before consensus.

Now look at Yahoo and Jerry Yang.

In February 2008, Microsoft offered $44.6 billion to acquire Yahoo. The board, led by Yang, rejected the bid as “substantially undervaluing” the company. Microsoft raised its offer to $33 per share. Yang rejected that too. Shareholders revolted. Carl Icahn joined the board. Yang stepped down as CEO in November 2008. The company cycled through four more chief executives in five years, and eventually sold its core business to Verizon in 2017 for roughly $4.5 billion.

That is not poor execution. That is generational value destruction on a staggering scale.

Or take OpenAI removing Sam Altman in late 2023. Within days, over ninety-five per cent of employees signalled they would leave. Microsoft offered to hire the entire workforce. The board discovered a brutal truth. Governance without the founder meant having no company to govern.

Those are the disasters.

But firing a founder is not always wrong.

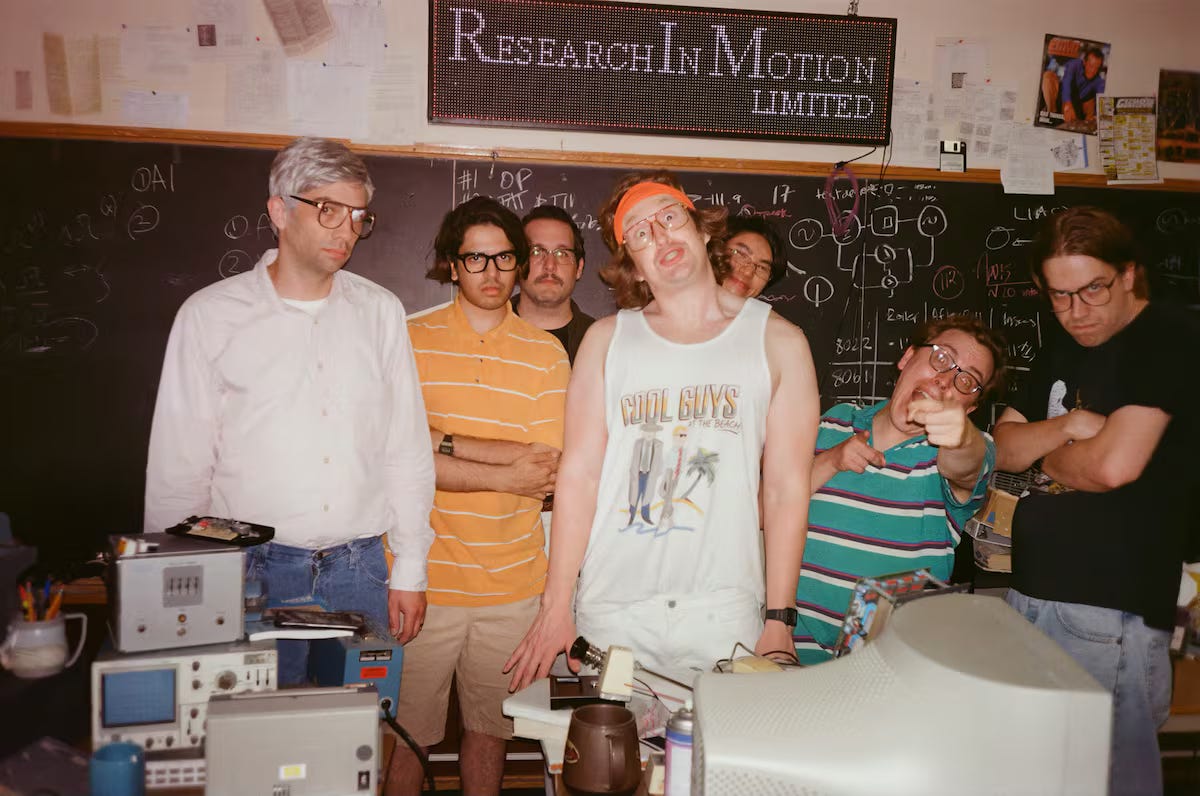

BlackBerry is a case study in founders misreading a platform shift. Co-CEOs Jim Balsillie and Mike Lazaridis clung to physical keyboards while Apple’s iPhone remade the entire category around touchscreens. After both stepped down in January 2012, the company pivoted into enterprise software and cybersecurity. It did not regain dominance, but it survived.

Tesla replaced its founding CEO Martin Eberhard in 2007 amid cost overruns and execution strain on the original Roadster programme. The leadership that followed was volatile and aggressive. It also forced an entire industry to electrify.

So what is the dividing line?

It is not charisma. It is not volatility.

It is whether the founder is still directionally right.

If the founder is still the engine, removal destroys value.

If the founder has become the brake, removal can unlock it.

Boards often fail because they remove founders for the wrong reason. They remove them because they are uncomfortable.

Professional operators optimise what exists. Founders create what does not.

If you replace the explorer too early, you institutionalise mediocrity.

The Seven Hundred Billion Dollar Gamble

While boards debate personalities, markets are engaged in a different act of conviction.

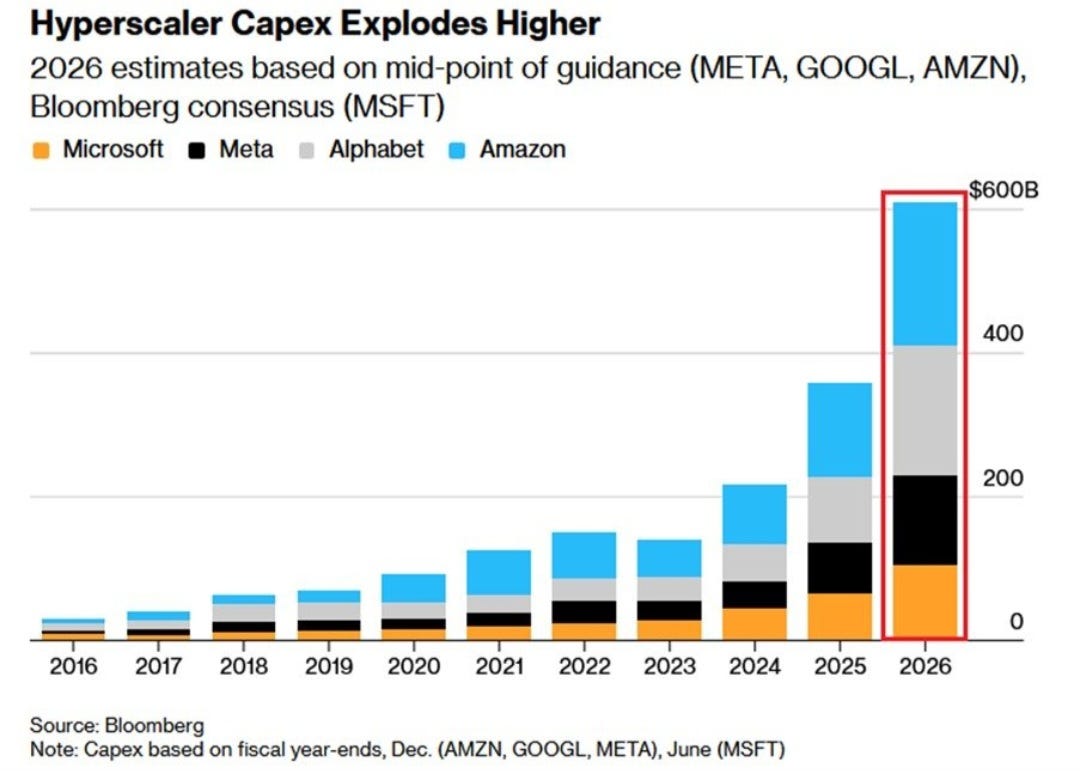

Amazon, Alphabet, Meta and Microsoft are collectively committing capital expenditure of between $635 billion and $700 billion in 2026. That is roughly double their combined spend in 2025, which was itself a record. A decade ago, these same four companies spent $31 billion between them. The scale of acceleration is without precedent in corporate history.

This is no longer asset-light software. This is industrial-scale infrastructure.

Amazon alone has guided $200 billion in capital expenditure this year. Alphabet is targeting $175 billion to $185 billion. Meta between $115 billion and $135 billion. Microsoft is tracking towards $120 billion. Even Oracle, which lacks the free cash flow of the hyperscalers, is raising $45 billion to $50 billion through debt and equity in a single year just to keep pace.

When capital spending surges at this scale, three things happen.

Free cash flow tightens. Morgan Stanley projects Amazon’s free cash flow will go negative in 2026, potentially by as much as $28 billion. Alphabet’s free cash flow could fall by ninety percent. Meta faces a similar compression. These companies are burning through their own abundance to build what they believe will become essential infrastructure.

Depreciation expands. Short-lived assets, primarily GPUs, now dominate the spend. Microsoft reported that roughly two-thirds of its capital expenditure goes on processors that will be obsolete within years. Every chip purchased today is a bet that demand arrives before the hardware depreciates.

Valuation narratives get tested. High multiples assume scalable margins and capital efficiency. Massive front-loaded infrastructure bets assume demand arrives on schedule. If autonomous agents become real economic actors, these firms will own the rails. If adoption lags, margin compression will follow.

Markets are already sorting winners from losers.

In the short term, the money flows to whoever sells the shovels. Nvidia’s data centre revenue hit $51.2 billion in its most recent quarter, up sixty-six percent year on year. CoreWeave, the neocloud provider that rents GPU clusters to the hyperscalers, has surged over thirty percent since January and carries a $55.6 billion backlog. Vertiv, which makes the power and cooling systems that keep these facilities alive, just reported organic orders up 252 percent and a backlog of $15 billion. Eaton, the electrical switchgear manufacturer, is riding the same wave as data centres compete for grid connections. These are not software companies. They are the picks, shovels and dynamite of the AI gold rush, and the market is pricing them accordingly.

In the medium term, the carnage is in software. The iShares Tech-Software ETF has retreated roughly thirty percent from its late 2025 highs. Salesforce is down twenty-six percent year to date. ServiceNow has fallen twenty-eight percent. Intuit has dropped over thirty-four percent. Atlassian plunged thirty-five percent in a single week. Traders at Jefferies are calling it the SaaSpocalypse. The trigger was not a recession. It was the realisation that every dollar an enterprise spends on AI infrastructure is a dollar not spent on another software seat. Hedge funds have shorted roughly $24 billion in software stocks in 2026 alone. The per-seat pricing model that defined a generation of cloud businesses is being repriced in real time.

The hyperscalers themselves sit in the middle. Amazon and Microsoft are down twelve and sixteen percent respectively on the year, weighed by free cash flow concerns. Alphabet and Meta have held steadier. Investors are treating them as both builders and potential beneficiaries. If AI agents generate real economic output, the companies that own the compute layer will capture enormous value. If the payback period stretches, their balance sheets absorb the pain.

In the long term, the question is structural. The shift is not from one software vendor to another. It is from software as a tool for humans to AI as the worker itself. Companies that own unique data, control critical infrastructure or sit at the foundation of the new stack will command premium valuations. Companies that merely organise information in a browser window will not. The age of the seat licence is ending. What replaces it, whether consumption-based pricing, outcome-based billing or something else entirely, will define the next era of technology investing.

The market is not panicking. It is repricing.

And then there is physics.

AI is not abstract. It consumes electricity at extraordinary density.

Data centres are now competing with households for grid capacity. In Monterey Park, California, a proposed 250,000 square foot hyperscale data centre would consume 434 million kilowatt hours per year. That is 1.7 times the entire city’s residential electricity usage, equivalent to powering 40,000 homes in a city with only 20,000 households. Hundreds packed City Hall in January. The council voted unanimously for a moratorium, and is now drafting an outright ban.

This is the new frontier. Not prompts. Power stations.

Countries are responding differently.

The Middle East is building at extraordinary speed. Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund has backed HUMAIN, a dedicated AI infrastructure company, which is constructing eleven data centres across two campuses in the Kingdom with ambitions to become the world’s third largest AI provider. The UAE has agreed with American partners to build a five gigawatt AI campus in Abu Dhabi, with an initial 200 megawatt cluster going live this year. Gulf sovereign wealth funds have committed roughly $2.5 trillion to major technology investments. These are not plans. Construction is underway.

Europe is investing in sovereign compute to avoid dependency. The EU’s €200 billion AI Continent Action Plan includes AI Gigafactories, nine new AI-optimised supercomputers being procured across the bloc in 2025 and 2026, and a new Cloud and AI Development Act to guarantee EU-based compute capacity. European sovereign cloud spending is expected to triple from $6.7 billion in 2025 to over $23 billion by 2027. The philosophy is clear. If you do not control the infrastructure, you do not control the intelligence.

The United States is attempting to balance private capital intensity with public infrastructure constraints. The handful of hyperscalers alone may account for a meaningful share of total US non-residential investment spending this year, enough to move the dial on GDP.

And the United Kingdom must decide where it stands.

The government’s AI Opportunities Action Plan and AI Growth Zones are steps in the right direction. Blackstone’s £10 billion AI campus in Blyth, Microsoft’s partnership with Nscale to build the UK’s largest supercomputer, Google’s £5 billion data centre programme, and the new Stargate UK project with OpenAI and NVIDIA all represent real momentum. The £150 million AI Pathfinder programme for sovereign GPU deployment shows intent.

But the question remains whether these commitments add up to enough. The UK is targeting 500 megawatts of AI Growth Zone capacity by 2030, with one zone scaling to a gigawatt. Saudi Arabia’s HUMAIN alone is building 1.9 gigawatts by that same date. The National Energy System Operator estimates data centres could drive up to 71 terawatt hours of additional electricity demand over the next 25 years. The grid is already under strain.

Consumer. Or builder.

Because AI leadership will not be decided solely in code.

It will be decided in concrete and copper.

🚀 Final Thought

Firing founders too early is a board choosing comfort over edge.

Underbuilding infrastructure out of caution is a nation choosing safety over competitiveness.

Overbuilding blindly is just as dangerous.

The hardest decisions in business are not operational. They are philosophical.

Do you preserve the edge. Or do you smooth it out.

Do you build ahead of demand. Or wait and hope.

Taste cannot be spreadsheeted.

Physics cannot be negotiated.

The next decade will expose those who forget either.

Until next Sunday,

David