The Sunday Signal: Is Google Running Scared?

Issue #30 – Friday 21 November 2025 - Essential insights on AI, power and place.

The Bottom Line Up Front

This week exposes a strange split in the story Silicon Valley is telling the world about AI.

On one side, Google’s CEO sits with the BBC in California and warns of an AI bubble. He urges caution. He says AI tools are prone to errors. He suggests we should rely on search, which in practice means Google. The BBC treats this like a public service announcement rather than a highly strategic piece of corporate framing.

On the other side, in the same week, the CEO of Anthropic goes on 60 Minutes and says AI could eliminate half of all entry level white collar jobs and push unemployment to between ten and twenty per cent. That is not a bubble. That is a shockwave. That is economic upheaval on a scale the BBC interview did not even acknowledge.

I have been working from Málaga this week, a city that has reinvented itself by embracing technology without surrendering its identity. Watching these interviews while sitting in a place built on renewal, not fear, clarified something important. When powerful institutions begin to feel control slipping away, they do not tell you the future. They tell you the version of the future that protects their position in it.

Three pieces this week:

Is Google Running Scared? A BBC interview dressed up as journalism, a tech giant defending its tollbooth, and a rival CEO warning of a jobs crisis that Google politely avoided.

From Failing French to Understanding Spain. The Babel fish arrives, quietly reshaping how we take part in everyday life.

Working From Málaga. What a city on Spain’s southern coast can teach Yorkshire about confidence, reinvention and vision.

If power follows distribution and opportunity follows place, this week shows that both are shifting at once.

Is Google Running Scared?

The BBC loves a pilgrimage to Silicon Valley. This week it made the journey to Google’s headquarters for an “exclusive” with Sundar Pichai. The setting was familiar. Logos in the background, neutral-toned interview room, a calm CEO explaining the future.

The story, though, was not neutral at all.

Pichai warned that we may be in the middle of an AI bubble. He told the BBC there is “irrationality” in the current boom and that if the bubble bursts, “no company is going to be immune, including us.”

He compared the moment to the early internet. Back then, he said, there was too much investment, but the technology was so profound that the excess was worth it. AI, he argued, will be the same. Profound, but overheated. Transformative, but risky.

So far, so balanced.

Then came the line that really mattered. Asked about the limits of AI tools, Pichai told the BBC that people should not “blindly trust” them, that they are still “prone to errors” and should be treated as just one source of information among many. That is sensible enough. But he went further.

“This is why people also use Google Search,” he said, “and we have other products that are more grounded in providing accurate information.”

There it is. Do not trust AI too much. Trust search. In other words, trust the product that keeps Alphabet’s cash machine running.

At this point an impartial interviewer might have asked some obvious questions.

If AI is too unreliable to trust, why is Google rushing to put AI summaries at the top of every search result? Why is Gemini being pushed into Maps, Gmail and the browser itself? If AI is dangerous when others deploy it, why is it safe when Google does? If this really is a bubble, why has Alphabet’s valuation roughly doubled this year on the back of the AI story?

Instead, the BBC did what it increasingly does with big tech. It let the narrative stand. A few gentle prompts about energy, climate targets and jobs. Some soaring footage of data centres. No challenge to the basic conflict of interest.

The result was an extraordinarily helpful piece of public relations.

Pichai had three messages to land.

First, that AI is both an opportunity and a threat. The dotcom comparison makes it sound like he is looking after the public, when in reality, he is explaining why regulators should cut Google some slack if valuations wobble.

Second, that users should be wary of AI answers in general, but should feel safe inside products “grounded” in Google’s existing search stack. That is a neat way of telling people to keep going through the tollbooth that funds Alphabet, instead of trying a rival assistant in a rival browser.

Third, that Alphabet has a special “full stack” advantage. Chips, data centres, YouTube, DeepMind, search. This is meant to reassure investors and politicians that it is better to trust the incumbent with all this power than risk new players.

None of these points is neutral. All of them serve the same strategic goal. Keep control of the front door to the web.

🎧 Listen to the full interview here

Two CEOs, Two Stories

The same week the BBC gave Pichai a soft landing, another AI chief sat in a very different studio and told a very different story.

On 60 Minutes, Dario Amodei, the CEO of Anthropic, said that without serious intervention, AI could wipe out half of all entry level white collar jobs and push unemployment to somewhere between 10 and 20 per cent within the next one to five years.

Pressed by Anderson Cooper, he confirmed the quote. Entry-level consultants, junior lawyers, financial analysts, and other white collar workers are directly in the firing line. AI models, he said, are already “quite good” at much of what they do, and the worry is not just the scale of the impact, but the speed. Faster than previous technological waves.

Amodei was not talking about some distant science fiction scenario. He pointed to the reality on the ground. Tech firms have already begun cutting staff while AI systems take over more code, more analysis, more routine knowledge work. In Anthropic’s own case, he noted that Claude helps write the majority of the company’s internal code.

You do not have to agree with his exact numbers to see the pattern. One CEO of a leading AI lab is warning that entry level white collar work could be gutted and unemployment could spike into double digits. Another is telling the BBC that AI tools are not quite dependable enough to trust and that we should keep relying on search.

Put those messages together, and the picture sharpens.

If Amodei is roughly right, AI will compress the career ladder. The safest jobs will belong to those who already have experience, capital or rare skills. Entry-level knowledge workers will struggle to find a foothold. That is a social problem on a historic scale.

Yet the BBC did not connect the dots. In a week when one AI chief is effectively saying, “prepare for a white collar jobs shock,” another is allowed to suggest that the main thing viewers should do is keep using Google.

Impartial journalism would have put those two interviews side by side and asked what happens when an AI-driven jobs shock arrives in a world where one company still controls most of the routes to information, training and opportunity.

Instead, we got the latest episode of “Tech Royalty visits Auntie,” complete with respectful nods and gentle concern.

The Real Bubble

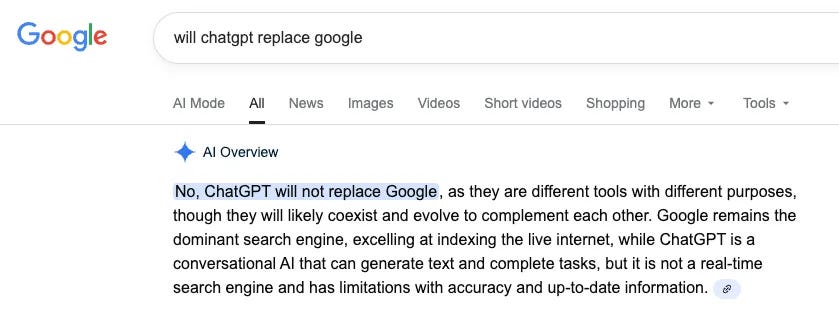

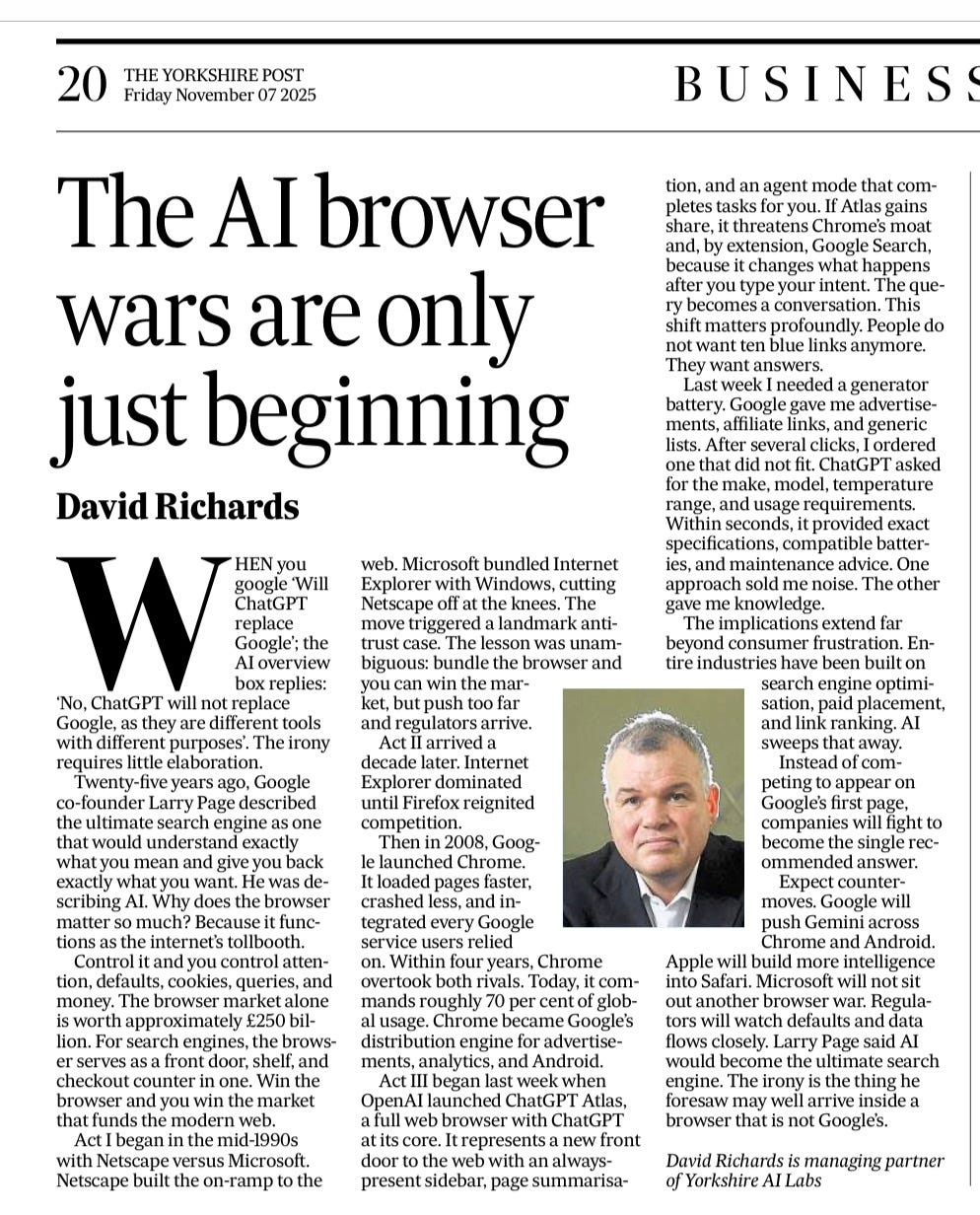

Two weeks ago, in my Yorkshire Post column on the AI browser wars, I argued that Chrome is not a mere convenience. It is the tollbooth of the modern internet. Control the browser, and you control what happens after a user types their intent. Google became an empire by owning that moment.

Now that moment is under attack. OpenAI’s Atlas browser turns a search into a conversation. Instead of ten blue links, you get a single answer and a path to action. Instead of bouncing between tabs, you ask an agent to complete a task. Every one of those tasks is a trip that no longer passes through a Google results page.

Seen from Mountain View, that is the real bubble risk.

Not that AI will fail, but that it will succeed somewhere else.

The BBC should understand this. Its own charter promises impartiality and scrutiny, especially when interviewing people whose commercial interests are obvious. Instead, it delivered a friendly platform where the CEO of the dominant search engine could tell viewers that AI is unreliable and that the safest response is to rely on his own product.

I do not blame Pichai for taking that opportunity. He is doing his job. I do blame a public service broadcaster for confusing access with journalism.

When the most powerful firms in history sit down to shape the story of the future, the role of the interviewer is not to nod along and cut to B-roll. It is to ask the one question the script is designed to avoid.

If AI is as profound as you say, and if your competitors believe it is about to rewrite the job market for an entire generation of workers, why should the rest of us accept that it must arrive wrapped inside your search engine?

From Failing French to Understanding Spain: The Babel Fish Arrives

Based on my weekly column in The Yorkshire Post this week.

I never enjoyed French. Our middle school teacher was far more passionate about her horses than about verbs or grammar. I disliked the subject so much that I once aimed for a zero in a French exam. Somehow I still ended up with seventeen per cent. They must have awarded marks for getting your name right.

All of which makes it striking that I am now sitting in a small coffee bar in a town just outside Málaga, listening to Spanish conversations that no longer feel completely out of reach. The rapid chatter drifts around the room. Today is different.

When we lived in California and undertook a major building project, most of the contractors were Mexican, and the man running the team had one key qualification. He spoke English. Each morning they would walk past our kitchen window chatting in rapid Spanish. On more than one occasion, a friend translated what they were saying, which made their later reaction even better. I eventually told the team that every word had been understood. The look on their faces was priceless.

There was one part of the language world that did captivate me. I am not a big science fiction fan, but I loved The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and its idea of the Babel fish, a tiny yellow creature you put in your ear. It feeds on brainwave frequencies and excretes a telepathic translation of whatever is being said around you, so Arthur Dent, the bewildered protagonist, can suddenly understand aliens.

Douglas Adams added a philosophical flourish. Because the Babel fish is so improbably useful, some characters argue that its existence is proof that God does not exist, and God promptly disappears in a puff of logic. A translation device so perfect that it undoes theology. For years, I assumed nothing like it would exist outside fiction.

Fast forward to Spain. Whenever we come here, I make an effort to speak Spanish. My intentions are good, my results inconsistent. When a waiter fires a rapid question at me, my dependable fallback is a confident “Si,” often delivered without the faintest idea what I have agreed to. On one memorable occasion, when left to my own devices, I managed to order enough food to feed about twenty people. It was only me at the table.

This week I tried something different. Apple has begun rolling out real-time Live Translation for AirPods Pro, powered by Apple Intelligence and running largely on the device. It is still in beta, but I decided to test it properly here in Málaga. You press the stem, speak, listen to the reply, and the translated English arrives in your ear. To my surprise, I found myself having short but meaningful conversations with locals and understanding far more than I usually would.

These tools are early versions and do not claim to be flawless, but even now they are useful. Only months ago this feature did not exist. In a short span of time, systems like this will support almost every kind of everyday conversation.

This is about more than holiday convenience. Language barriers create social friction. They shrink confidence and make you feel like an outsider, even when people are friendly. I saw this in California when the building firm relied entirely on the owner simply because he spoke English. When technology begins to soften barriers like that, even slightly, the effect is liberating. You take part. You risk mistakes. You feel included.

Sitting here, listening to the translation whisper into my ear as people chat about the day’s plans, I find myself returning to that French exam. My reward for scoring seventeen per cent was private French lessons on Saturday mornings. Back then, the Babel fish was nothing more than a playful idea from a book.

Today, in a small café on the Costa del Sol, it feels far less like a joke. It turns out the Babel fish did not need to evolve. It just needed engineers, silicon and a pair of AirPods.

Working From Málaga: Lessons For Yorkshire

In March, in the Yorkshire Post, I wrote about how Yorkshire can learn from Spain’s revival. I argued that Málaga’s story is not just about sunshine and tourists. It is about a port city that decided to reinvent itself as a hub of technology, art and advanced services, without abandoning its industrial roots.

This week I have been working from Málaga, laptop open in the same cafés where I test Apple’s translation tools. The view from the street is even more instructive than the statistics.

Walk from the port to the historic centre and you see layers of economic history in a single afternoon. Cranes and container traffic at the harbour. Renovated warehouses turned into co-working spaces. A Picasso museum full of visitors from across Europe. Startups, advertising cybersecurity roles in English and Spanish. A university that feeds talent into local firms rather than exporting it all to Madrid.

Spain felt like a byword for crisis a decade ago. Today, it is quietly outgrowing many of its European peers. Málaga has been part of that shift. The city took infrastructure that once served maritime trade and repurposed it for digital work. Fibre where rails used to be. Software instead of ship repair. The industrial DNA remained. The sectors changed.

Yorkshire should pay attention.

Our own history is written in mills, forges and pitheads. Bradford’s chimneys. Sheffield’s steel. Hull’s docks. In the nineteenth century, those places were at the frontier of global innovation. The question for our century is whether we are willing to treat ourselves that way again.

Málaga’s success has three ingredients that Yorkshire can borrow.

First, it treated quality of life as an economic asset, not a luxury. The city cleaned up its waterfront, invested in culture and made the centre somewhere people actually want to live. That attracts talent. When your engineers can finish work and walk on the beach, you do not have to beg them to stay. Leeds and Sheffield have their own versions of this in the Peaks, the Dales and a vibrant food and music scene. We should double down on that rather than pretending that grey skies are destiny.

Second, it used existing strengths as a launchpad. Málaga did not try to become the next Silicon Valley. It leaned on logistics, tourism and a strong local university to build new clusters in cybersecurity, fintech and creative industries. Yorkshire can do the same with advanced manufacturing, health data and green energy. The ingredients are already there in places like the AMRC, our NHS trusts and the Humber’s offshore wind assets.

Third, it welcomed outsiders without losing its character. You hear German, English and Scandinavian voices everywhere, but the city still feels unmistakably Spanish. That balance matters. If Yorkshire wants to attract founders and engineers from around the world, it has to do so on its own terms, not by pretending to be London on a budget.

Working from Málaga this week has been a practical reminder that geography is not fixed. Cities can choose their story. So can regions.

The same technology that lets me join calls with teams in Sheffield from a bar in Andalusia also means a start-up in Rotherham can sell to clients in Barcelona or Boston. AI translation will make that even easier. When language stops being a wall, second-tier cities stop being second-tier.

Spain’s transformation is not perfect. Youth unemployment is still high. Wages lag Germany and France. But the trajectory is clear. A country that was once written off as the sick man of Europe is now showing what a second act can look like.

Yorkshire has every right to write one of its own.

Final Thought

Two interviews. Two stories. One reality.

In California, the CEO of Google tells the BBC that AI is overhyped, risky and should be treated with caution. He says users should not trust AI too much and should rely on search instead. The BBC nods along. No challenge. No hard questions. No acknowledgement that this advice conveniently protects the business model of the world’s dominant search engine.

Meanwhile, in New York, the CEO of Anthropic tells 60 Minutes that AI could erase half of all entry level white collar jobs and push unemployment to levels not seen in modern history. He describes a disruption that is already beginning. He warns that the impact will be faster than anything we have seen before.

Google says be careful. Anthropic says be prepared.

The BBC gives one message a soft landing. The other barely gets noticed.

And yet, outside those studios, in cities like Málaga, something far more important is happening. People are working, learning, building and adapting. New industries are taking root. New skills are emerging. Translation barriers are falling. A regional port city has become a global tech hub without needing permission from Silicon Valley.

Yorkshire can learn from that. Britain can learn from that. The BBC could learn from that.

The future does not belong to those who ask us to slow down so their old model can survive. It belongs to the places and people confident enough to move forward anyway.

Read The Sunday Signal first every Friday on Substack.

Public release follows on Sunday.