The Sunday Signal: Digital Revolutions, Manufacturing Resistance, and History's Harsh Lessons

Essential Insights on Tech’s Impact, Leadership Lessons, and Navigating Human Potential Issue #16 – Sunday 3 August 2025

⏱️ 10 min read

The Bottom Line Up Front

Thirty-four years ago this week, Tim Berners-Lee quietly launched the world's first website, demonstrating how transformative innovations often emerge from solving practical problems. Meanwhile, British manufacturers' irrational resistance to cloud computing threatens our competitive position, echoing historical patterns where industries that rejected new technology became cautionary tales. The message is clear: embrace innovation or join history's footnotes.

When Revolutions Begin Without Fanfare

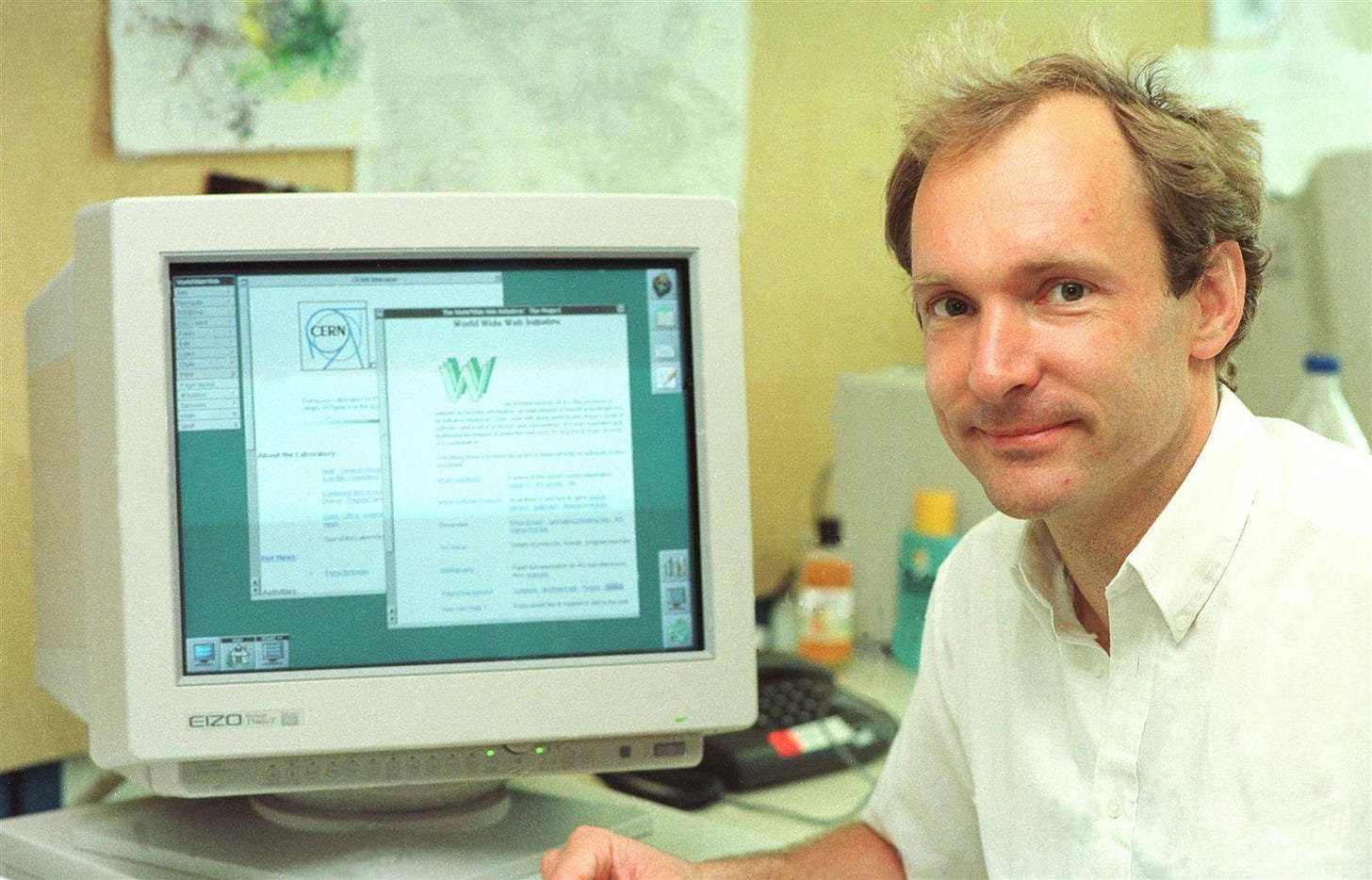

Thirty-four years ago this week, a British physicist at CERN performed an act that would fundamentally alter human civilisation. Tim Berners-Lee published the world's first website at info.cern.ch, a page so unremarkable in appearance that its revolutionary nature went entirely unnoticed. No press releases heralded this moment. No ceremonies marked the occasion.

Visiting that original site today (remarkably, still accessible) offers a striking lesson in the power of simplicity. Plain text on a white background describes the WorldWideWeb project with academic precision. No images, no multimedia, just hyperlinked information about protocols and specifications. The contrast with today's internet reveals not merely technological progress but a fundamental shift in how humanity processes and shares knowledge.

Berners-Lee's motivation emerged from practical frustration rather than visionary ambition. Scientists at CERN stored research across multiple computer systems, creating inefficient information silos. His solution integrated three core technologies: HTML for structuring content, HTTP for transferring data, and URLs for addressing resources. This framework solved an immediate problem whilst inadvertently providing the architecture for our digital future.

What distinguishes Berners-Lee's contribution extends beyond technical innovation to philosophical courage. Faced with the choice between personal enrichment and collective advancement, he chose the latter. By releasing the Web's protocols freely, rejecting patents and licensing fees, he established a precedent that open infrastructure creates exponentially more value than proprietary systems.

The Web's evolution accelerated through critical policy decisions. When the Clinton administration chose to exempt online commerce from sales tax, they catalysed a commercial revolution. Traditional retail hierarchies dissolved within a decade. Geographic barriers vanished. Small enterprises gained access to global markets.

Yet these transformations brought unforeseen challenges. The same openness that democratised information also enabled its weaponisation. Misinformation spreads with viral efficiency. Privacy erodes systematically. Digital monopolies concentrate unprecedented power.

As we reflect on this anniversary, one lesson stands paramount: revolutionary change often emerges from solving mundane problems with elegant simplicity. The modest website still living at info.cern.ch reminds us that transformative technologies need not arrive with fanfare. Sometimes the most revolutionary act is solving a problem well, then trusting humanity with the solution.

The Irrational Fear Holding British Manufacturing Back

Almost a decade ago, I toured Sheffield's Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre with Professor Keith Ridgway. We paused beside a researcher developing a visual fault-detection application for aerospace components. When I asked about cloud computing, his response was blunt: "No, they'll never use cloud."

That chance encounter revealed something deeply concerning about British manufacturing's relationship with technological progress. Despite proven advantages, substantial sectors of our industrial base continue resisting cloud adoption with an irrationality that defies business logic.

My introduction to cloud computing came at Silicon Valley conferences in the mid-2000s. Initially puzzled by Amazon's presence among technology pioneers, I soon understood: AWS was quietly revolutionising how computing resources were accessed and utilised. Amazon had built enormous capacity for Christmas peaks, then realised this infrastructure lay idle most of the year. Their solution? Democratise access to computing power.

The transformation has been staggering. In the late 1990s, half my startup's venture funding vanished immediately on hardware. Today, I can summon 2,000 high-powered computers from my phone for an hour for just a few pounds. Yet many British manufacturers resist, often due to fundamental misunderstandings about "public cloud" infrastructure.

The term "public cloud" emerged to differentiate shared infrastructure from private data centres. It does not mean public access. Many manufacturers mistakenly fear their data will become publicly accessible, which is simply false.

Security concerns against cloud adoption lack foundation entirely. Do companies genuinely believe they possess resources matching major cloud providers' security capabilities? I've watched specialised teams at cloud control centres neutralise attempted breaches before they materialise. Financial services reported a 47% increase in cyber-attacks between 2022 and 2023, highlighting vulnerabilities in traditional systems.

Even America's CIA adopted cloud technology over a decade ago, awarding AWS a $600 million contract in 2013. This makes manufacturers' reluctance seem not misplaced but utterly illogical.

Humanity's greatest recent breakthroughs, including COVID-19 vaccines, Mars rover missions, and genomic sequencing advances, depended on cloud computing. The competitive advantages extend beyond security to artificial intelligence, machine learning, predictive maintenance, and global supply chain collaboration.

British manufacturing's strength has always been early technology adoption. From steam power in textile mills to Sheffield's Bessemer Converters, our industrial success thrived through embracing innovation rather than fearing the unknown.

We must move past outdated views and evaluate cloud computing's benefits through evidence. This evolution offers British manufacturing opportunities to reclaim technological leadership. The question isn't whether transformation will occur, but whether Britain leads or follows.

When Industries Refuse to See the Future: Ten Cautionary Tales

History offers harsh judgement on those who resist technological inevitability. As British manufacturers hesitate over cloud adoption, they might consider these sobering precedents:

Kodak's Digital Denial (1970s-2000s): The company that invented digital cameras in the 1970s suppressed their own innovation, fearing film sales disruption. Competitors seized the opportunity. Kodak filed for bankruptcy in 2012.

Blockbuster's Streaming Blindness (2000s): Offered Netflix for $50 million in 2000, Blockbuster executives laughed. A decade later, Blockbuster was bankrupt while Netflix transformed global entertainment.

BlackBerry's Touch of Death (2000s-2010s): Clinging to physical keyboards while dismissing touchscreens as faddish, BlackBerry watched Apple's iPhone redefine mobile computing. Market dominance evaporated within years.

Nokia's Software Stubbornness (Late 2000s-2010s): The Finnish giant underestimated software's importance, maintaining outdated systems while iOS and Android revolutionised smartphones. From controlling 40% of mobile markets to near irrelevance.

British Luddites' Lost Battle (Early 1800s): Textile workers violently resisted mechanised looms, believing technology threatened livelihoods. Industrialisation proceeded regardless, reshaping Britain's economy while resisters were forgotten.

Western Union's Telephone Folly (1876): Rejecting Alexander Graham Bell's "impractical" invention, Western Union watched Bell create AT&T, which dominated telecommunications for a century.

Xerox PARC's Innovation Abandonment (1970s-1980s): Developing graphical interfaces and computer mice, Xerox failed to commercialise breakthroughs. Apple and Microsoft built empires on these discarded innovations.

Royal Navy's Steam Scepticism (1830s-1850s): Dismissing steam power for traditional sails, Britain's naval supremacy faltered until expensive modernisation restored competitive position.

Qing Dynasty's Fatal Isolation (18th-19th centuries): Rejecting foreign industrial technologies, China's rulers presided over technological stagnation, leading to vulnerability and imperial collapse.

Borders' Digital Disaster (1990s-2000s): Outsourcing online sales to Amazon while resisting digital transformation, Borders vanished while Amazon redefined global commerce.

Each example shares common themes: dismissing transformative potential, protecting existing models, and believing established advantages provide permanent protection. None survived their miscalculation.

🚀 Final Thought

The Innovation Imperative: Learning from History's Technology Resisters

Three decades separate Tim Berners-Lee's quiet revolution from today's cloud computing resistance in British manufacturing. The parallel is striking: transformative technology available freely, offering clear advantages, yet meeting institutional resistance rooted in misunderstanding rather than legitimate concern.

History's verdict on technological resistance is unanimous and unforgiving. From Kodak's digital denial to the Royal Navy's steam scepticism, the pattern remains consistent: those who protect yesterday's advantages sacrifice tomorrow's opportunities.

British manufacturing stands at a crossroads. We can embrace cloud computing's proven benefits (enhanced security, reduced costs, infinite scalability, AI capabilities) or join history's cautionary tales alongside Blockbuster, Nokia, and countless others who chose familiarity over progress.

The Web succeeded because one person solved a practical problem then trusted others with the solution. Cloud computing offers similar pragmatic advantages. The greatest risk isn't adopting new technology; it's refusing to see its inevitability.

As we commemorate the Web's 34th anniversary, let's remember: revolutions rarely announce themselves. They begin with someone solving a problem, sharing a solution, and trusting progress over protection. British industry must choose whether to lead transformation or become another historical footnote warning future generations about the cost of resistance.

The choice, as always, remains ours.

Until next Sunday,

David

David Richards MBE is a technology entrepreneur, educator, and commentator. The Sunday Signal offers weekly insights at the intersection of technology, society, and human potential.